Carbohydrates, alongside proteins and fats, are one of the three major macronutrients that form the foundation of a healthy, balanced diet. They serve as the body’s primary source of energy and play a crucial role in numerous metabolic processes. Despite their importance, carbohydrates, particularly sugars, have become the subject of ongoing debate in nutrition science and public health. Concerns about sugar consumption, its impact on obesity, diabetes, and other health outcomes have led to conflicting opinions and widespread confusion. To truly understand the role of carbohydrates in our diet, it’s essential to first explore what carbohydrates actually are, how different types of sugars and starches function in the body, and why some are considered more beneficial to our health than others.

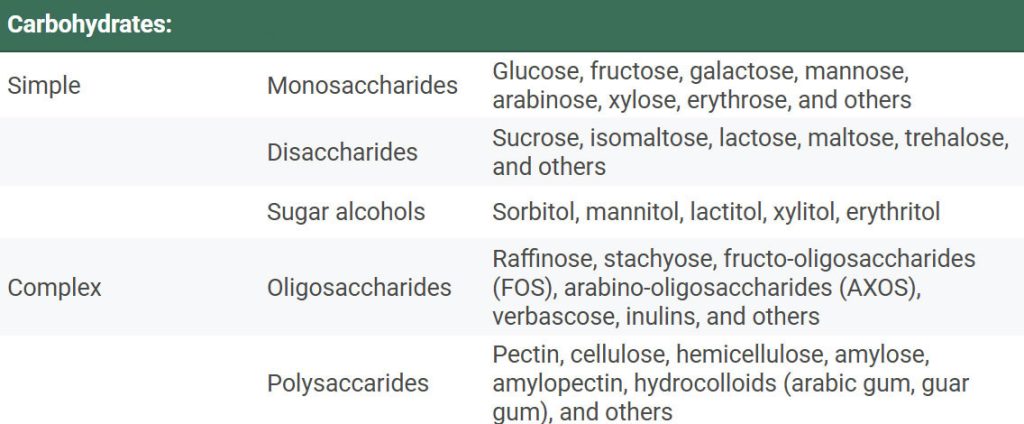

Carbohydrates are relatively stable organic molecules made up of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. They are found almost exclusively in foods of plant origin, where they are synthesized through photosynthesis, a process in which plants convert carbon dioxide and water into energy-rich compounds using sunlight. In the human diet, carbohydrates are typically the major source of energy, providing between 50–70% of total daily caloric intake in many populations. Carbohydrates can be broadly divided into three categories: sugars, starch, and non-starch polysaccharides. These carbohydrates are further classified into simple and complex types, based on their chemical structure and the body’s ability to digest and absorb them (see Table 1.).

Simple carbohydrates include monosaccharides, disaccharides, and sugar alcohols. Monosaccharides are the simplest forms of sugar and include glucose, fructose, and galactose. These single-unit sugars can be absorbed directly through the intestinal wall and are quickly utilized by the body for energy. Disaccharides, such as sucrose (glucose + fructose) and lactose (glucose + galactose), are composed of two linked monosaccharides. These sugars occur naturally in many foods and require enzymatic digestion before absorption. Interestingly, the type of bond between the monosaccharides influences how easily the sugar is broken down during digestion. Of these, sucrose, commonly known as table sugar, is by far the most prevalent sugar in the human diet, contributing to approximately 14% of total energy intake in some populations. Sugar alcohols, like sorbitol and xylitol, are either naturally occurring or synthetically produced compounds that resemble sugars but are not absorbed in the small intestine. Because of this, they are often used as low-calorie sweeteners and can have a mild laxative effect when consumed in large quantities.

Complex carbohydrates include oligosaccharides and polysaccharides. Oligosaccharides are carbohydrate chains composed of 3 to 15 monosaccharide units. They are not digested by human enzymes, but instead undergo fermentation by bacteria in the large intestine. Common oligosaccharides include raffinose, stachyose, and verbascose, which are typically considered unavailable to human metabolism. On the other hand, inulins, a type of oligosaccharide found in foods like chicory and onions, are considered physiologically relevant due to their prebiotic effects and potential health benefits. Polysaccharides, also referred to as complex carbohydrates, are long chains of monosaccharide units (>15). The most well-known polysaccharides in the human diet are starches, which include amylose (a linear chain) and amylopectin (a branched chain). These starches are digestible and serve as a primary energy source. In contrast, non-starch polysaccharides are a diverse group of compounds that are not broken down by human digestive enzymes. This category includes various types of dietary fiber, which play important roles in gut health, satiety, and metabolic regulation.

Among all the monosaccharides, glucose plays the most critical role in human metabolism. The majority of carbohydrates enters the bloodstream as glucose so it is the major sugar circulating in the bloodstream and serves as the primary energy source for many tissues, most notably the brain, which relies almost exclusively on glucose under normal physiological conditions. After carbohydrate ingestion and digestion, glucose is absorbed in the small intestine and enters the bloodstream. This rise in blood glucose levels triggers a finely tuned neuroendocrine response, primarily regulated by the hormones insulin and glucagon. Insulin is secreted by the β-cells of the pancreas in response to elevated blood glucose. It facilitates the uptake of glucose by muscle and adipose tissues and promotes its storage as glycogen in the liver and muscles. When glycogen stores are full, excess glucose is converted into fat for long-term energy storage. Insulin also suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, the process of synthesizing glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, further helping to lower blood glucose levels. When blood glucose drops, such as during fasting or prolonged physical activity, insulin secretion decreases, and glucagon is released from the α-cells of the pancreas. Glucagon stimulates glycogenolysis, the breakdown of glycogen into glucose, especially in the liver, which supplies glucose to maintain normoglycemia during the first several hours of fasting. As glycogen reserves become depleted, the liver initiates gluconeogenesis, producing glucose from amino acids, lactate, or glycerol. Other hormones such as cortisol, growth hormone (GH), catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), and angiotensin II also support gluconeogenesis and mobilization of energy stores during prolonged fasting or stress. This homeostatic mechanism ensures that blood glucose remains within a narrow, optimal range. However, rapid or excessive increases in blood sugar (e.g., after consumption of high-glycemic foods) can lead to an exaggerated insulin response, occasionally followed by reactive hypoglycemia, a sudden drop in blood sugar, that may result in symptoms such as hunger, irritability, fatigue, trembling, or faintness.

Blood glucose levels reflect the balance between glucose input and its utilization or removal from the bloodstream. To better understand how different carbohydrate-containing foods affect blood glucose levels, the glycaemic index (GI) was developed as a comparative tool. The GI measures the ability of saccharides to raise blood glucose, assigning a value to each food based on how it impacts postprandial (after eating) blood sugar levels. More specifically, the glycaemic index is calculated by comparing the area under the blood glucose response curve for 50 grams of available carbohydrates from a test food to that of a reference food, usually pure glucose, which is assigned a GI value of 100. High-GI foods are digested and absorbed rapidly, leading to a sharp increase in blood glucose. These include foods like white bread, sugary cereals, and some processed snacks. Frequent consumption of high-GI foods has been linked to metabolic disturbances and is often considered less favorable from a health perspective. In contrast, low-GI foods, such as legumes, whole grains, and most vegetables, are digested more slowly and cause a gradual rise in blood glucose. These are associated with improved glycaemic control and are generally seen as more beneficial, particularly for individuals with insulin resistance or diabetes.

However, GI is only one part of the story. Another important factor is the glycaemic load (GL), which takes into account not only the quality (GI) but also the quantity of carbohydrates in a given portion of food. GL provides a more comprehensive picture of a food’s impact on blood glucose levels by multiplying the GI of a food by the amount of available carbohydrates per serving, and dividing by 100. This allows for a better understanding of how a typical serving will actually affect blood sugar. However, interpreting GI and GL values in isolation can be misleading. The glycaemic response to food is not determined by the carbohydrate alone, but also by numerous other factors, including the presence of fiber, fat or proteins in meal, food structure, cooking method, and individual physiological status, such as insulin sensitivity or metabolic health. For instance, elite endurance athletes may consume large amounts of high-GI foods (such as refined carbohydrates) to rapidly replenish glycogen stores, yet remain lean and metabolically healthy due to high energy expenditure and optimized glucose metabolism. In this context, it becomes clear that focusing solely on the type of carbohydrate or its GI value is insufficient. Dietary context, overall dietary patterns, and the metabolic needs of the individual must all be considered when evaluating the health impact of carbohydrates.

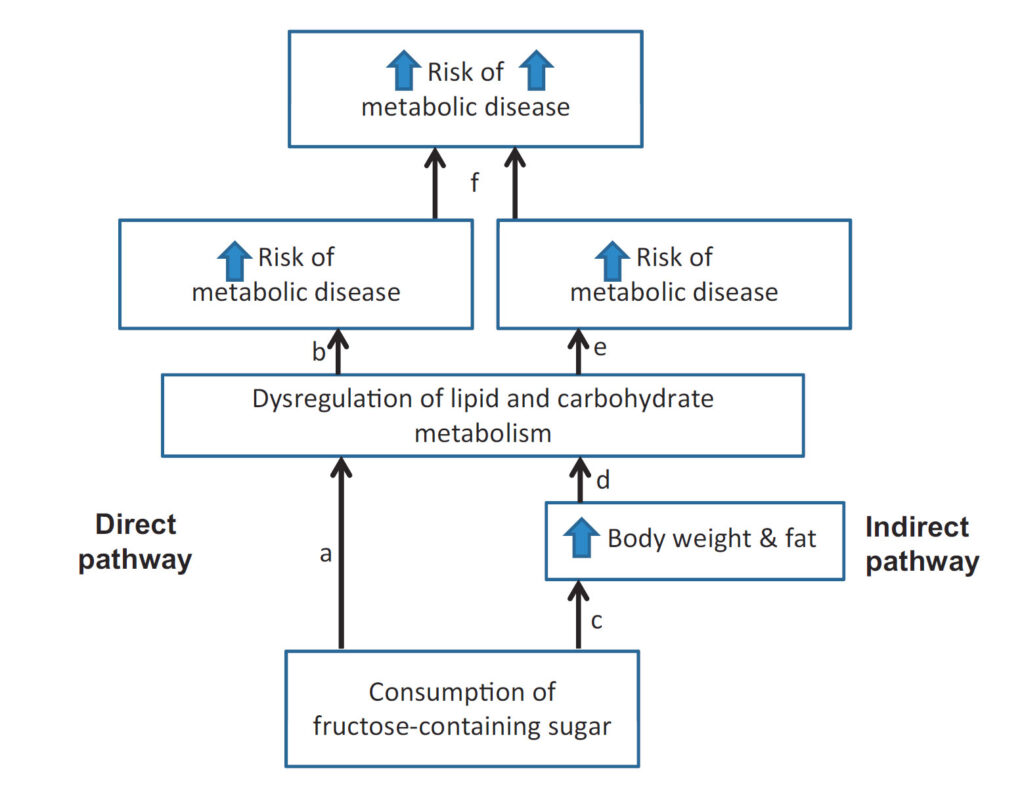

It has been suggested that diets with both high GI and high GL values may be associated with an increased risk of chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Therefore, managing both the type and amount of carbohydrate consumed is important for long-term metabolic health. While carbohydrates are an essential macronutrient and serve as the body’s primary energy source, excessive consumption, especially of refined carbohydrates and added sugars, has been linked to various metabolic disturbances and chronic diseases. The overconsumption of carbohydrates can affect the body both directly and indirectly (illustrated in Figure 1). One direct mechanism involves fructose, a key component of sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup, which has been shown to dysregulate both lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Fructose is primarily metabolized in the liver, where it can promote de novo lipogenesis, contributing to increased fat production, particularly when consumed in excess. Indirectly, high sugar intake contributes to positive energy balance, leading to increased body weight and fat accumulation. This, in turn, exacerbates metabolic dysregulation, further impairing lipid and glucose metabolism. Over time, these changes contribute to the development of insulin resistance, elevated triglyceride levels, and fat accumulation in organs such as the liver and pancreas.

Figure 1. Direct and indirect pathway by which overconsumption of sugar can lead to metabolic diseases. Directly, sugar consumption disrupts lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (a, b). Indirectly, sugar promotes weight and fat gain (c), which in turn dysregulates lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (d, e), ultimately increasing the risk of metabolic disease. Therefore, the risk of metabolic disease may be intensified when added sugar is consumed in diets that support weight and fat gain (f)..Sourced from Stanhope 2015.

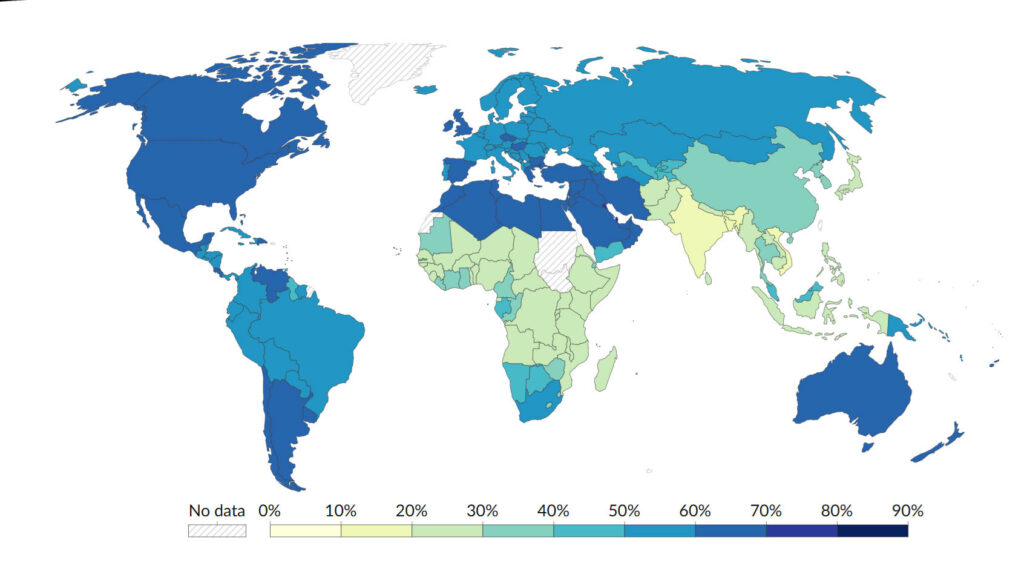

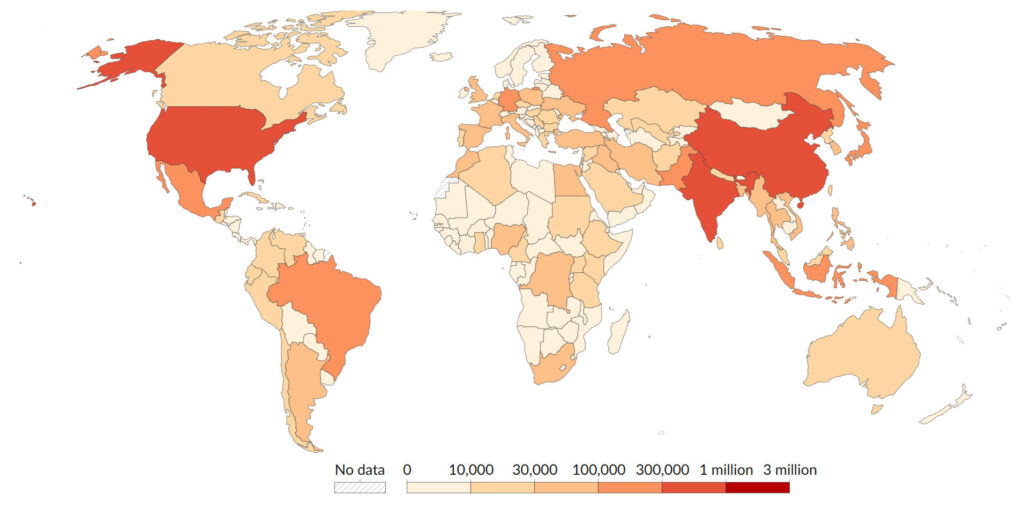

Obesity has emerged as a major global public health challenge, approaching pandemic proportions (Figure 2.). It is associated with profound physical and psychological consequences and represents a major risk factor for a range of chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers. Although obesity is influenced by multiple factors (including age, genetics, medications, and lifestyle), its primary cause is a persistent energy imbalance, where caloric intake exceeds expenditure over time. The metabolic effects of carbohydrate type also differ: fructose, for instance, promotes lipid accumulation in visceral adipose tissue, which is more strongly linked to metabolic disease, while glucose favors deposition in subcutaneous fat, considered relatively less harmful. Notably, when fructose is consumed in large quantities, it yields more fat than glucose and can lead to a net accumulation of fat in the liver due to an imbalance between lipid input and output. This process contributes significantly to the development of hepatic steatosis. In conditions of severe obesity and insulin resistance, additional changes in intestinal glucose handling occur. For example, the GLUT2 transporter, typically located on the basolateral membrane of enterocytes, has been observed to accumulate on the apical membrane of jejunal enterocytes, enabling passive diffusion of glucose directly into the bloodstream. This abnormal adaptation may further contribute to elevated postprandial glucose levels and worsen insulin resistance.

Figure 2. Proportion of adults who are overweight or obese, 2016. Sourced from World Health Organization – Global Health Observatory (2024) – processed by Our World in Data.

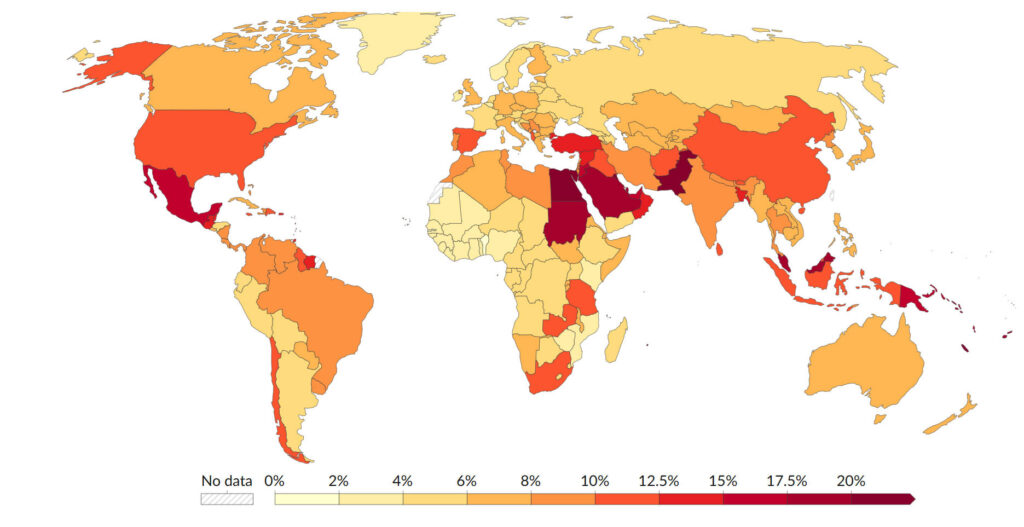

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide (see Figure 3.), first described over 3,000 years ago by ancient Egyptian and Indian physicians. Yet, it was not until 1922 that the first patient was successfully treated with insulin, marking a turning point in diabetes management. The primary diagnostic feature of diabetes is hyperglycemia, or elevated blood glucose levels. There are three main types of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition, in which the body’s immune system attacks and destroys the insulin-producing β-cells in the pancreas, resulting in insulin dependence. Type 2 diabetes is characterized by insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency. Gestational diabetes occurs during pregnancy and typically resolves after delivery. Among these, type 2 diabetes is by far the most prevalent and is strongly associated with both irreversible risk factors, such as age, genetics, race, and ethnicity, and reversible lifestyle-related factors, including diet, physical activity, and smoking. Diet plays a critical role in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes. High intake of refined carbohydrates and added sugars contributes to postprandial spikes in blood glucose, exacerbates insulin resistance, and promotes obesity, all of which increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. In individuals with obesity, excess fat accumulates in the liver and skeletal muscles, where it impairs insulin-mediated glucose uptake due to disruptions in intracellular insulin signaling. Fat accumulation can also occur in the pancreas, leading to dysfunction in insulin secretion. As a result, blood glucose levels rise, the pancreatic β-cells respond less effectively, and insulin production declines. This in turn causes glucagon levels to rise, further increasing blood glucose and perpetuating a harmful metabolic cycle. Importantly, not all carbohydrates affect metabolism equally. The metabolic impact varies based on the type and structure of carbohydrate consumed. Diets rich in whole fruits, vegetables, and fiber are associated with reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes. These foods contain antioxidants, phytochemicals, and slowly digestible carbohydrates, which collectively help modulate blood sugar and support insulin sensitivity. The public health burden of type 2 diabetes is considerable. Beyond the immediate effects on glucose regulation, the condition significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In fact, more than 50% of individuals with diabetes die as a result of heart disease or stroke, highlighting the systemic impact of prolonged hyperglycemia and poor metabolic control.

Figure 3. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus, 2021. Sourced from International Diabetes Federation (via World Bank) (2025) – processed by Our World in Data.

Given the strong link between high-glycaemic diets and metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, implementing dietary strategies to lower GI and GL of meals is essential for long-term metabolic health. One of the most effective strategies is to limit the amount of glycaemic carbohydrates, those that are rapidly digested and absorbed, leading to sharp increases in blood glucose. This includes reducing the intake of refined sugars and replacing them with low-glycaemic or non-glycaemic sweeteners. A wide range of alternatives exists, including non-caloric and low-calorie sweeteners such as stevia, aspartame, trehalose, and isomaltulose. While these substitutes can help lower postprandial glucose spikes, it is worth noting that some artificial sweeteners have been reported in certain studies to negatively affect gut microbiota and glycaemic control. Another effective method to reduce postprandial glycaemia is to slow the rate of gastric emptying. This can be achieved by combining carbohydrates with fats and proteins or by consuming meals rich in viscous soluble fiber. These additions help slow down the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, leading to lower and more stable blood glucose levels. Additionally, the digestion of carbohydrates in the small intestine can be modulated by the presence of natural compounds found in certain fruits and plants. For example, blackcurrants, apples, grapes, blueberries, L-arabinose, and chicory inulin fructans have been shown to slow enzymatic breakdown of carbohydrates. Furthermore, polyphenols found in apples and blackcurrants can influence glucose transporters, reducing the rate at which glucose enters the bloodstream. A cornerstone of glycaemic regulation is the adequate intake of dietary fiber. Fiber not only supports digestive health but also contributes to improved blood sugar control.

Dietary fiber plays a fundamental role in maintaining metabolic and gastrointestinal health and is a key component in strategies to reduce the glycaemic impact of meals. Historically, dietary fiber was defined as the portion of plant foods resistant to digestion by human enzymes, primarily non-starch polysaccharides and lignin. However, the modern definition has been expanded to include oligosaccharides, such as inulin, and resistant starches that are also resistant to digestion in the small intestine but undergo partial or complete fermentation in the large intestine by the gut microbiota. Dietary fiber is typically regarded as a low-calorie component of food, but its health benefits far exceed its caloric contribution. By resisting enzymatic digestion, fiber slows the passage of food through the gastrointestinal tract, thereby aiding in regular bowel function and helping to prevent conditions such as hiatal hernias, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcers, gallbladder disease, appendicitis, diverticular disease, colorectal cancer, and hemorrhoids. In terms of metabolic health, dietary fiber is associated with improved glycaemic control, even when overall caloric intake from carbohydrates, proteins, and fats remains unchanged. Increased fiber intake has been shown to reduce the need for insulin and medication in individuals with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, thanks to its capacity to slow glucose absorption and improve insulin sensitivity. Fiber also contributes to cardiovascular health. Some studies have shown that higher fiber consumption is associated with reduced serum LDL-cholesterol, lower blood pressure, and overall reduced risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). Specifically, soluble fiber is linked to improvements in systolic blood pressure and total cholesterol levels. There is also evidence that fiber intake may reduce the risk of certain cancers, particularly colorectal cancer, by delaying or preventing the formation of precancerous polyps. Additionally, fiber contributes to increased satiety, helping to regulate appetite and food intake. High fiber consumption has been associated with a 30% reduced risk of weight gain and obesity, which further contributes to the prevention of metabolic diseases. Importantly, fiber supports the immune system through its interaction with the gut microbiota. The human gastrointestinal tract is the largest immune organ in the body, and dietary fiber, especially fermentable fiber, stimulates the growth of beneficial bacterial strains such as Bifidobacteria, contributing to improved immune modulation and intestinal barrier integrity. Various analytical methods are used to determine dietary fiber content in foods, and as a result, there can be variations in the estimated fiber content across different food types and studies. Despite some debate about the optimal intake, most health authorities recommend a daily fiber intake of 25–35 grams for adults as part of a healthy, balanced diet.

While sugars play an essential role in human metabolism and are necessary for a healthy life, their overconsumption remains a significant concern. Although recent trends show a decline in sugar intake, many populations still consume more than 300% of the daily recommended amount of added sugars. Excessive sugar consumption is strongly associated with an increased risk of metabolic disorders, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Each year, millions of people die as a result of complications linked to chronically elevated blood glucose levels (see Figure 4), often driven by poor dietary habits and lack of physical activity. To mitigate these risks, it is advisable to consume carbohydrates in their natural matrix, accompanied by fiber, protein, and fat, which slow down glucose absorption and help maintain more stable blood sugar levels. In contrast, sugar-sweetened beverages, which deliver high doses of rapidly absorbable sugars, should be minimized. The impact of carbohydrates on health is determined by a complex interplay of factors: the type of carbohydrates, its molecular characteristics, and physiological effects (digestion, absorption, metabolic fate). Moreover, an individual’s physiological status, such as body composition, insulin sensitivity, and physical activity level, plays a crucial role in how carbohydrates are metabolized. For example, a lean and active individual will process sugars differently than someone with insulin resistance or obesity.

Figure 4. Deaths due to high blood sugar, 2021. Sourced from IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024) – with minor processing by Our World in Data.

Importantly, not all saccharides are the same, and dietary fiber stands out as a particularly beneficial carbohydrate. There are two main approaches to increasing fiber intake. Utilizing fiber-rich whole foods, such as whole grains and by-products of fruit and vegetable processing. Extracting and isolating fiber components to be added into processed food products. However, fiber added as a functional ingredient may not provide the same health benefits as fiber naturally present in whole foods. In some cases, excessive intake of added fiber can even lead to gastrointestinal discomfort or impair the absorption of certain nutrients. Nevertheless, increasing overall fiber intake remains a public health priority, especially given the large gap between current consumption levels and official dietary recommendations. A balanced approach that emphasizes whole food sources of fiber, while judiciously using added fiber when necessary, may help bridge this gap and support long-term metabolic health.

Resources:

Anderson, J. W.; Baird, P.; Davis, R. H. Jr.; Ferrari, S.; Knudtson, M.; Koraym, A.; Waters, V.; Williams, Ch. L. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutrition Reviews, 2009, 67, 4, 188-205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x

Brealey, D.; Singer, M. Hyperglycemia in Critical Illness: A Review. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 2009, 3, 6, 1250-1260.

Brouns, F. Saccharide Characteristics and Their Potential Health Effects in Perspective. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2020, 7, 75. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.00075

Faraque, S.; Tong, J.; Lacmanovic, V.; Agbonghae, Ch.; Minaya, D. M.; Czaja, K. The Dose Makes the Poison: Sugar and Obesity in the United States – a Review. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Science, 2019, 69, 3, 219-233. https://doi.org/10.31883/pjfns/110735.

IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024) – with minor processing by Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/deaths-due-to-high-blood-sugar (accessed on 2 April 2025)

International Diabetes Federation (via World Bank) (2025) – processed by Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/diabetes-prevalence (accessed on 2 April 2025)

Jayedi, A.; Soltani, S.; Jenkins, D.; Sievenpiper, J.; Shab-Bidar, S. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2022, 62, 9, 2460-2469. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1854168

Lunn, J.; Buttriss, J. L. Carbohydrates and dietary fibre. British Nutrition Foundation: Nutrition Bulletin, 2007, 32, 1, 21-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2007.00616.x

Nie, Q.; Chen, H.; Hu, J.; Tan, H.; Nie, S.; Xie, M. Effects of Nondigestible Oligosaccharides on Obesity. Annual Reviews of Food Science and Technology, 2020, 11, 12.1-12.29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-032519-051743

Pasmans, K.; Meex, R. C. R.; van Loon, L. J. C.; Blaak, E. E. Nutritional strategies to attenuate postprandial glycemic response. Obesity reviews, 2022, 23, 9, e13486. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13486

Reynolds, A.; Mann, J.; Cummings, J.; Winter, N.; Mete, E.; Moringa, L. T. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet, 2019, 393, 434-445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9

Sami, W.; Ansari, T.; Butt, N. S.; Ab Hamid, M. R. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review. International Journal of Health Sciences, 2017, 11, 2, 65-71.

Stanhope, K. L. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 2015, 53, 1, 52-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10408363.2015.1084990

Tirone, T. A.; Brunicardi, F. Ch. Overview of Glucose Regulation. World Journal of Surgery, 2001, 25, 461-467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002680020338

WHO, Global Health Observatory, (2024) – processed by Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-of-adults-who-are-overweight?time=2016 (accessed on 2 April 2025)