Cultivated meat may seem like a futuristic innovation, but at its core, it starts with something deeply biological: cells. More specifically, it starts with the right kind of cells, those that have the ability to multiply, grow, and form muscle tissue. Skeletal muscle, the primary component of meat, is a highly organized tissue composed predominantly of multinucleated muscle fibers, accompanied by connective tissue, intramuscular fat, vasculature, and nerves. The overall composition of meat typically comprises approximately 90% muscle fibers and 10% fat and connective tissue, though this proportion varies by species and anatomical origin. At the cellular level, the main contributors to the structure and properties of meat are skeletal muscle cells (myocytes). However, other cell types such as adipocytes, fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and hematopoietic lineage cells play critical supportive roles in tissue architecture and influence organoleptic qualities such as texture and flavor. For example, intramuscular fat contributes not only to nutritional value but also to species-specific taste and tenderness.

In vivo, muscle tissue originates during embryogenesis, when myogenic precursor cells (myoblasts) proliferate, align, and fuse into multinucleated myotubes, which mature into contractile myofibers. These fibers are organized into functional units embedded in an extracellular matrix, and surrounded by lipid deposits, capillaries, and neuronal inputs. Reproducing such complexity in vitro for cultivated meat production begins with a key decision: the selection of the starting cell type. This choice has profound implications, technical, economic, and regulatory, and directly affects the efficiency of biomass generation, the fidelity of tissue development, and the final quality of the cultivated product. The cultivated meat industry currently lacks a unified agreement on the most suitable cell types for development. The selected cells must meet several criteria such as self-renewal capacity and the potential to differentiate. Estimates suggest that approximately 2.9 × 10¹¹ muscle cells are needed to produce just 1 kilogram of wet meat, underlining the importance of choosing a cell source with robust proliferative capacity. Among the various candidates, stem cells remain the most promising due to their inherent ability to both proliferate and differentiate.

The term stem cell was first introduced in the late 19th century by Valentin Haecker and Theodor Boveri, referring to cells capable of giving rise to various tissues during embryonic development. Today, stem cells are defined by two fundamental properties: self-renewal (the ability to undergo mitosis and generate identical daughter cells over multiple cycles) and differentiation (the capacity to develop into specialized cell types depending on their intrinsic potency and microenvironmental signals). These properties are used to classify stem cells into a hierarchical spectrum based on their developmental potential. Totipotent cells represent the highest level of plasticity. Found only in the zygote and early blastomeres, they can give rise to an entire organism, including both embryonic and extraembryonic tissues. However, they are not considered true stem cells due to their limited self-renewal capacity and rapid loss of totipotency during development. Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), can differentiate into all somatic cell types of the three germ layers, ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm, but not into extraembryonic tissues like the placenta. Importantly, they possess unlimited self-renewal potential in vitro under appropriate cultivation conditions, making them highly attractive for cultivated meat applications. Multipotent stem cells, such as adult stem cells including mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) or muscle satellite cells, are lineage-restricted and can differentiate into a limited range of cell types within a particular tissue or organ system (e.g., myogenic, adipogenic, or chondrogenic lineages). Although their proliferation is more limited compared to PSCs, they are more readily isolated from adult animals and generally present fewer ethical or regulatory concerns. Unipotent progenitors are committed to a single lineage but still retain self-renewal capacity. Examples include satellite cells responsible for muscle regeneration in vivo.

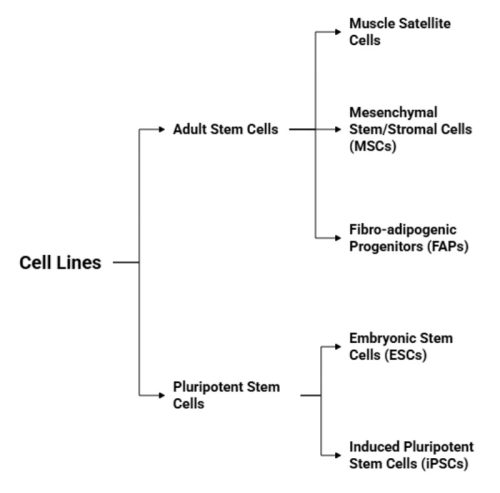

Two broad categories have emerged as central to cultivated meat development: adult stem cells and pluripotent stem cells (see Figure 1.). Each of these offers distinct advantages and limitations in terms of scalability, genetic stability, differentiation efficiency, and regulatory acceptance. In the following sections, we will examine these cell types more closely and explore the rationale behind their use in cultivated meat systems. Despite the promise of stem cells, most foundational research has been conducted in human or murine models, and translation to livestock species, such as cattle, pigs, or chickens, remains a significant technical hurdle. Each species poses unique challenges in terms of stem cell isolation, expansion, differentiation, and adaptation to serum-free or food-compatible media. As such, ongoing research is focused on optimizing protocols for agricultural species, ensuring that selected cell lines combine high proliferative capacity with the ability to form structured, functional tissues relevant to meat quality.

Figure 1. Classification of cell lines for cultivated meat production.

Adult stem cells

Adult stem cells are undifferentiated cells found in postnatal tissues that typically remain in a quiescent (non-dividing) state until activated by specific signals, such as tissue injury or mechanical stress. Once activated, they re-enter the cell cycle and contribute to tissue repair, growth, and regeneration through rapid cellular proliferation. This regenerative ability makes them an attractive and practical starting point for cultivated meat production. In fact, adult stem cells are currently the most widely used cell type in the cultivated meat field, primarily due to their relative accessibility and regulatory familiarity. Among the various adult cell types, three major progenitor or stem cell populations play a central role in muscle tissue and have been identified as promising for meat production: muscle satellite cells, mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), and fibro/adipogenic progenitors (FAPs). Together, MSCs and FAPs have the potential to generate nearly all the key cell types required for creating structured and flavorful cultivated meat.

While protocols for isolating and expanding these cells are well established in humans, adapting these methods to livestock species such as cows, pigs, or poultry remains a technical challenge. Species-specific differences in cell surface markers, cultivation conditions, and responsiveness to growth factors often necessitate substantial optimization. Despite their advantages, adult stem cells have a limited proliferative capacity, which can constrain scalability. Unlike pluripotent stem cells, they cannot divide indefinitely. To address this, researchers have explored methods to extend the replicative lifespan of adult stem cells, either by suppressing differentiation-related pathways (e.g., using inhibitors of key myogenic transcription factors) or by applying genetic engineering techniques to enhance genes linked to cell cycle progression and proliferation. While these approaches are promising, they must be carefully evaluated for regulatory acceptability and consumer perception, particularly when genetic modifications are involved. Nevertheless, improving the expansion potential of adult stem cells remains a key area of innovation, as it directly influences the feasibility and cost-efficiency of cultivated meat production at industrial scale.

Muscle satellite cells are one of the most established and well-studied adult stem cell populations relevant to cultivated meat. Discovered in 1961 in frog muscle tissue, these cells are essential for postnatal muscle growth, repair, and regeneration. In vivo, they reside in a unique niche, beneath the basement membrane of skeletal muscle fibers, nestled between the myofiber and the surrounding basal lamina. This anatomical positioning allows them to remain quiescent under normal conditions and rapidly activate upon injury or mechanical stress. For cultivated meat production, satellite cells are typically obtained through muscle biopsy, a well-established and relatively straightforward procedure. Once isolated, they can be expanded in vitro and induced to differentiate into myotubes and mature myofibrils, forming the essential contractile structures of muscle tissue. Despite their relevance, satellite cells exhibit limited proliferative capacity, and their ability to expand depends heavily on factors such as animal species, age of the donor, and the specific muscle tissue from which they are derived. Nonetheless, they are currently the most commonly used cell type in cultivated meat production, largely because they naturally follow the myogenic lineage, minimizing the complexity of differentiation protocols. Satellite cells have been successfully isolated and cultivated from several livestock and aquatic species, including bovine (cattle), porcine (pig), ovine (sheep), galline (chicken), and piscine (fish). Their ease of isolation, combined with a high degree of differentiation efficiency into muscle fibers, makes them particularly attractive for scalable meat production. However, it is worth noting that cultivation efficiency remains relatively low, and cell senescence after repeated passages is a challenge for large-scale manufacturing. Still, satellite cells are generally well tolerated from a regulatory standpoint, since they are derived directly from food-producing animals and do not require extensive manipulation. This gives them a favorable profile not only from a technical perspective, but also in terms of public perception and regulatory acceptance.

Another important population of adult stem cells explored for cultivated meat production is mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. These cells are multipotent progenitors that play a supportive yet significant role in tissue regeneration and homeostasis, particularly in the aftermath of muscle damage. In the native tissue environment, MSCs modulate inflammatory responses, assist in extracellular matrix remodeling, and interact with myogenic cells to facilitate repair processes. MSCs can be isolated from multiple tissue sources, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and skeletal muscle, via minimally invasive biopsy techniques. Although their proliferation capacity is limited, they are more abundant than muscle satellite cells and relatively straightforward to extract and cultivate. MSCs demonstrate the ability to differentiate into several lineages, adipogenic, chondrogenic, and fibrogenic, although their myogenic potential is minimal, and differentiation efficiency remains a challenge for meat-specific applications. Nevertheless, MSCs are valuable in cultivated meat systems for their ability to give rise to support cells, such as adipocytes and fibroblasts, which contribute to the texture, juiciness, and flavor profile of the final product. In fact, incorporating intramuscular fat through the adipogenic differentiation of MSCs is seen as a key factor in replicating the organoleptic complexity of traditional meat. MSCs have been isolated and studied across several agriculturally relevant species, including bovine, galline, ovine, and porcine sources, although interspecies differences in expansion rate, differentiation, and media requirements remain key areas of ongoing research. Due to their versatility and ease of acquisition, MSCs continue to be explored not only as standalone progenitors but also in co-cultivation systems that aim to better mimic the native tissue microenvironment.

Fibro-adipogenic progenitors are a distinct population of mesenchymal-derived cells residing in the interstitial space of skeletal muscle. Unlike muscle satellite cells, which directly contribute to myofiber formation, FAPs do not give rise to myotubes, but instead play a critical supportive role in the regeneration, organization, and structural integrity of muscle tissue. Their presence is essential for maintaining the extracellular matrix and for facilitating cross-talk between various muscle-resident cell types. FAPs exhibit limited proliferative capacity, but they are capable of differentiating into adipocytes and fibroblasts, two important non-myogenic cell types found in conventional meat. In the context of cultivated meat, FAPs can be isolated via muscle biopsy, and established protocols from human models have been adapted to bovine and porcine species. Though they are less frequently used as the primary cell source, they are increasingly recognized as key contributors to achieving a multi-cellular, tissue-like structure that closely mimics conventional meat. By combining FAPs with muscle satellite cells or other progenitor populations, researchers can better reproduce the complex cellular architecture of muscle tissue, potentially enhancing the realism and sensory quality of cultivated meat products.

Pluripotent stem cells

In addition to adult stem cells, pluripotent stem cells are emerging as a promising alternative for cultivated meat production. These cells are defined by their ability to differentiate into any cell type derived from the three germ layers, thereby covering all the cellular constituents of meat, including muscle fibers, adipocytes, fibroblasts, and vascular elements. One of the most attractive features of pluripotent stem cells is their unlimited proliferative capacity. Unlike adult stem cells, which have a finite division potential and can lose functionality with repeated passaging, PSCs are immortal under appropriate cultivated conditions. This makes them a compelling option for scalable meat production, especially in long-term manufacturing scenarios where continuous biomass generation is required. Despite these advantages, PSCs pose significant technical and practical challenges. While human and murine PSCs, particularly embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells, have been extensively studied, the development of livestock-derived PSC lines is still in its infancy. Protocols for the derivation, maintenance, and directed differentiation of bovine, porcine, avian, or piscine PSCs are either underdeveloped or entirely lacking, making their implementation in cultivated meat production less straightforward. Moreover, PSCs require more time, resources, and complex conditions to differentiate into mature, functional cell types suitable for food production. Their cultivation often involves costly growth factors, stricter environmental control, and multi-step differentiation protocols, which can affect economic feasibility. In contrast, adult stem cells such as satellite cells or MSCs are more directly lineage-committed, allowing faster and simpler routes to terminal differentiation. Nevertheless, the theoretical potential of PSCs remains unmatched, particularly if robust, serum-free and food-compatible protocols can be developed for livestock species. If these barriers can be overcome, PSCs may offer a renewable, versatile, and highly standardized cell source for future cultivated meat technologies, potentially even enabling the generation of engineered tissues that closely resemble whole cuts of meat with vascularization and multi-lineage complexity.

Embryonic stem cells represent the earliest form of pluripotent cells, isolated from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, a transient structure that forms approximately 5 days after fertilization in mammals. These cells possess indefinite proliferative capacity and the ability to differentiate into nearly all cell types of the adult body. ESCs are thus truly pluripotent, making them one of the most versatile cell types available for biotechnological applications. Research on ESCs began in the 1980s using mouse models, and by the late 1990s, human ESCs had been successfully cultivated. Since then, ESCs have been shown to differentiate into a wide range of specialized cells, including hematopoietic, neural, myocardial, and adipose cells. This immense potential has driven interest in their application across regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and, more recently, cultivated meat production. In theory, ESCs offer exceptional advantages for cultivated meat. Their unlimited expansion potential, combined with the capacity to differentiate into all relevant meat cell types, makes them a highly promising candidate for scalable, long-term biomass generation. Some experimental data suggest that ESCs could outperform other stem cell types in terms of efficiency and consistency when optimized for meat cell lineages. However, no specific peer-reviewed studies have yet demonstrated the full potential of ESCs in large-scale cultivated meat systems.

Despite their promise, ESCs come with significant ethical, technical, and regulatory challenges. Their derivation typically involves the destruction of early-stage embryos, which raises animal welfare and bioethical concerns, particularly if the source embryos are derived from livestock species. These concerns may limit consumer acceptance and complicate the regulatory approval of food products derived from ESCs. Furthermore, undifferentiated ESCs carry a risk of forming teratomas (a type of tumor), making precise control over differentiation critical for safe application. The differentiation of ESCs into desired meat cell types depends on multiple variables, including cell density, cultivation media composition, growth factor concentrations, and whether fetal bovine serum (FBS) is used, an issue that also affects the ethical and sustainability profile of the process. Moreover, ESC derivation and long-term cultivation protocols are still under development for many agricultural species. While ESC lines have been established in species such as bovine, porcine, ovine, avian, and piscine models, they are less well-characterized and often more difficult to maintain compared to their murine or human counterparts. In summary, ESCs represent a highly potent but controversial option for cultivated meat development. Their scientific potential is immense, but successful adoption will depend on ethical sourcing, regulatory clarity, and technical progress in directing their differentiation toward safe and desirable food components.

A transformative moment in stem cell biology came in 2006, when researchers in Japan led by Shinya Yamanaka discovered a method to reprogram terminally differentiated somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. These artificially generated cells exhibit the hallmark features of embryonic stem cells, including indefinite self-renewal and pluripotency, but are derived without invading embryos. The creation of iPSCs typically begins with skin fibroblasts, which are genetically reprogrammed by overexpressing a defined set of transcription factors. These factors effectively reset the epigenetic and transcriptional profile of the adult cell, restoring a state of pluripotency. The process is time-consuming, usually taking 1–2 weeks for mouse cells and 3–4 weeks for human cells, and is currently characterized by low efficiency, with success rates ranging between 0.01% and 0.1%. Nevertheless, advances in delivery methods, vector systems, and cultivation conditions are steadily improving both yield and safety. Unlike ESCs, iPSCs do not require embryos, which significantly reduces ethical and regulatory barriers. These advantages have positioned iPSCs as a highly attractive candidate for cultivated meat production, especially as protocols for livestock species (such as bovine, porcine, galline, and ovine) continue to develop. Despite their promise, several technical challenges remain. The reprogramming process is biologically demanding, often resulting in somatic mutations, genomic instability, or epigenetic memory that may influence differentiation behavior. In the context of cultivated meat, iPSCs hold particular appeal because of their unlimited proliferation potential and flexibility in differentiating into multiple relevant cell types, including muscle, fat, connective tissue, and vascular components. However, the differentiation protocols for iPSCs in livestock species are not yet fully optimized, and no commercial-scale cultivated meat product has so far been produced from iPSC-derived cells. That said, in 2009, a significant milestone was reached when porcine iPSCs were successfully generated, offering a promising foundation for future applications in agriculture. In conclusion, iPSCs represent a highly versatile and ethically favorable alternative to embryonic stem cells for cultivated meat. While technical barriers must still be addressed, ongoing research is rapidly closing these gaps. The ability to derive pluripotent cells from any individual animal opens new possibilities not only for scalable meat production, but also for species preservation, customization, and traceability in the food system of the future.

The journey to cultivated meat begins not in a bioreactor, but in the biology of cells. Selecting the right cell type, whether adult or pluripotent stem cells, is a foundational decision that determines the scalability, quality, and sustainability of the final product. Each cell source brings its own set of advantages and challenges, from ease of isolation to ethical considerations and regulatory pathways. While adult stem cells currently dominate due to their practicality and regulatory familiarity, pluripotent stem cells may open new frontiers in precision and tissue complexity. As research continues and technologies advance, the development of robust, food-safe, and efficient cell lines across multiple species will be key to transforming cultivated meat from scientific promise into everyday reality on our plates.

Resources:

Giglio, F.; Scieuzo, C.; Ouazri, S.; Pucciarelli, V.; Ianniciello, D.; Letcher, S.; Salvia, R.; Laginestra, A.; Kaplan, D. L.; Falabella, P. A Glance into the Near Future: Cultivated Meat from Mammalian and Insect Cells. Small Science, 2024, 4, 2400122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smsc.202400122

Lee, D.-K.; Kim, M.; Jeong, J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Yoon, J. W.; An, M.-J.; Jung, H. Y.; Kim, C. H.; Ahn, Y.; Choi, K.-H.; Jo, C.; Lee, C.-K. Unlocking the potential of stem cells: Their crucial role in the production of cultivated meat. Current Research in Food Science, 2023, 7, 100551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100551

Lee, S. Y.; Lee, D. Y.; Yun, S. H.; Lee, J.; Mariano, E. Jr.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.; Han, D.; Kim, J. S.; Hur, S. J. Current technology and industrialization status of cell-cultivated meat. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 2024, 66, 1, 1-30. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2023.e107

Ozhava, D.; Bhatia, M.; Freman, J.; Mao, Y. Sustainable Cell Sources for Cultivated Meat. Journal of Biomedical Research & Environmental Sciences, 2022, 3, 11, 1382-1388. https://doi.org/10.37871/jbres1607

Ravikumar, M.; Powell, D.; Huling, R. Cultivated meat: research opportunities to advance cell line development. Trends in Cell Biology, 2024, 34, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2024.04.005

Reiss, J.; Robertson, S.; Suzuki, M. Cell Sources for Cultivated Meat: Applications and Considerations throughout the Production Workflow. International Journal of Molecular Science, 2021, 22, 7513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147513