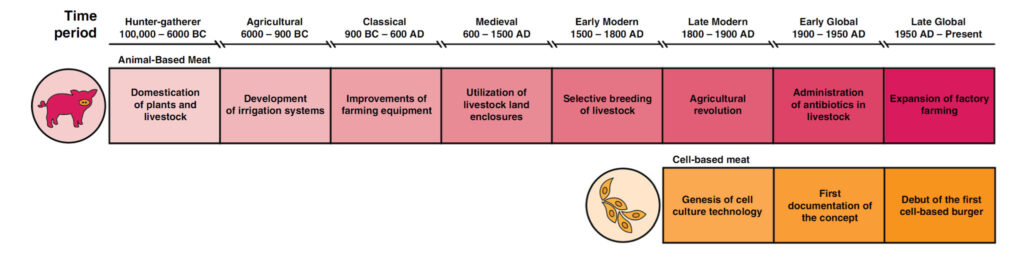

Figure 1. The history and evolution of animal based and cell based meat. Sourced from Rubio et al. 2020 with modifications.

Long before cultivated meat became a scientific reality, visionaries, writers, and scientists speculated about the possibility of producing meat without raising and slaughtering animals. These early ideas ranged from science fiction literature to bold predictions from scientists and politicians, reflecting a long-standing fascination with food technology. In 1894, French chemist Pierre Eugène Marcellin Berthelot envisioned a future where meat, milk, and eggs could be synthesized in factories by the year 2000. Just a few years later, in 1897, the science fiction novel Auf Zwei Planeten introduced a similar concept, imagining advanced civilizations with engineered food production. By the early 20th century, political and scientific figures were making even more precise predictions. In 1930, British Secretary of State for India Frederick Smith speculated about the emergence of “self-replicating steaks”, where “a piece of meat of any size and juiciness could be grown from a ‘mother’ steak.” A year later, Winston Churchill, in his article Fifty Years Hence (The Strand Magazine, 1931), proposed that instead of growing an entire chicken just to eat a specific part, we could grow only the desired pieces in a suitable medium. He wrote, “We shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing, by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium. Synthetic food will, of course, also be used in the future.” These futuristic visions were popularized in science fiction, where authors imagined bioreactors producing meat in space colonies and advanced societies. Books such as The Space Merchants (1952), The Martian Way (1952), and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) introduced the concept of growing meat in bioreactors, a notion that, at the time, seemed like pure fantasy but is now becoming a reality.

The development of tissue engineering from the 1950s to the 1970s played a significant role in the groundwork for cultivated meat, although the field’s initial focus was on medical applications. During this period, scientists primarily explored ways to grow and manipulate living tissues for regenerative medicine, organ transplantation, and wound healing. They conducted research to understand how cells grow, differentiate, and interact with their environment, with the goal of developing techniques to regrow damaged tissues and organs using scaffolds, growth factors, and controlled environments that mimic the body’s natural conditions. Key breakthroughs in cell cultivation techniques, bioreactors, and synthetic scaffolds enabled the expansion and differentiation of cells outside the human body. Although these innovations were originally intended for medical purposes, they established fundamental principles that would later be applied in the food industry. The ability to cultivate and expand cells in a controlled environment became a key technological foundation for cultivated meat production, as it demonstrated that muscle and fat cells could be grown outside a living organism. While the idea of using tissue engineering for food was still decades away from commercial realization, these early scientific efforts proved that cultivating animal cells was possible. Without the pioneering research in medicine and biotechnology, the concept of cultivated meat would have remained purely theoretical.

The late 20th century saw the first practical steps toward the development of alternative proteins and cultivated meat. These years marked the transition from speculative ideas to real-world innovation and early research. In 1982, the first vegan burger was introduced in the UK by Gregory Simms. While this was not cultivated meat, it represented an important shift toward meat alternatives and demonstrated growing consumer interest in ethical and sustainable food options. By the 1990s, the idea of cultivated meat took a step closer to reality. In 1995, NASA received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to research the feasibility of producing cultivated meat as a food source for long-duration space missions. This was a pivotal moment, as it marked the first institutional research into cultivated meat as a potential food source, bringing the concept from fiction into the realm of experimental science. NASA successfully cultivated muscle tissue from the common goldfish (Carassius auratus) in Petri dishes, with samples ranging from 3 to 10 cm in length. In 1999, Willem van Eelen became the first person to fill patents that laid the groundwork for what is now known as cultivated meat. Since van Eelen’s pioneering work, many attempts to cultivate meat have followed. Researchers, institutions, and private companies have expanded on his vision, refining cell culture techniques, optimizing growth conditions, and developing scalable production methods. His early efforts are widely recognized as the foundation for the modern cultivated meat industry, which continues to grow and evolve today.

After the first laboratory experiments, research on cultivated meat gradually expanded to universities worldwide. Some of the first academic institutions to explore this field included Maastricht University, Harvard, and Tufts University, where scientists investigated various approaches to tissue engineering and cell growth optimization. The first startups emerged during the early 2010s, bringing new investments and innovations. However, despite the promising technology, development was slowed by financial and technological barriers. The production process was expensive, scalable manufacturing solutions were lacking, and tissue cultivating in lab conditions still faced significant technical challenges. As early as 2001, NASA experimented with cultivated turkey meat as a potential food source for astronauts on long-duration space missions. The work of NASA paved the way for further studies, and in 2002, the NRC/Tauro Applied Bioscience Research Consortium also developed cultivated goldfish meat, marking another milestone in the exploration of commercial cell-based meat production. In 2003, the world witnessed the first public tasting of cultivated meat as part of an art project rather than a scientific or commercial initiative. Artists and researchers Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr presented their project, “Disembodied Cuisine,” at the L’Art Biotech exhibition in France (see Figure 2.). The project aimed to explore the possibility of growing meat without animal sacrifice through cell cultivation. As part of their experiment, they biopsied skeletal muscle cells from a frog and grew them on biopolymer scaffolds. Throughout the exhibition, live frogs remained on display as part of the artistic statement. On the final day of the show, the cultivated frog meat was cooked and eaten during a dinner at a museum in Nantes, while four live frogs were released into a local pond. This artistic experiment was the first time people ate cultivated meat, which started conversations about the ethics and technology behind it.

Figure 2. “Disembodied Cuisine,” at the L’Art Biotech exhibition in France. Sourced from Simonsen 2015.

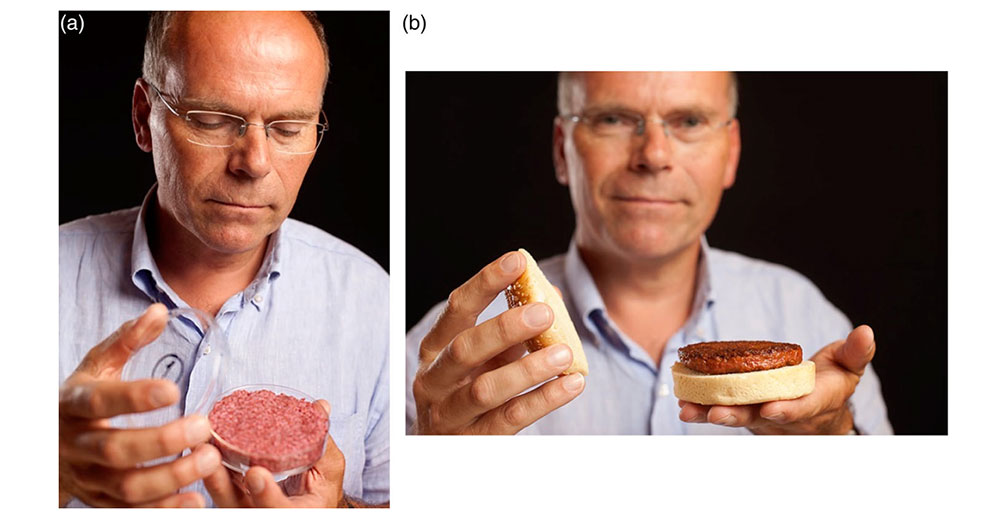

A major milestone in the development of cultivated meat occurred in 2013, when a team from Maastricht University, led by Dr. Mark Post, unveiled the world’s first cultivated hamburger (see Figure 3.). The burger, which cost $330,000 to produce, consisted of a five-ounce cultivated beef patty grown from stem cells extracted from a cow’s shoulder over a period of three months. The unveiling took place during a globally broadcast event in London, where a panel of sensory judges tasted the burger and noted that it had a texture and flavor similar to conventional beef. The hamburger consisted of 10,000 strips of myotubes engineered within a hydrogel matrix. However, to achieve a look and feel closer to a traditional hamburger, the muscle-like tissue had to be supplemented with additional components, including beetroot juice for color, saffron and caramel for flavor, and bread crumbs along with a binder to improve texture. This demonstration proved that the scientific production of cultivated meat was possible. Following the groundbreaking success of Mark Post’s cultivated burger, further advancements in the field continued. In 2016, the startup Memphis Meats (now known as Upside Foods) introduced a cultivated meatball, demonstrating significant progress in reducing production costs. Unlike Post’s $330,000 burger, this meatball was ten times cheaper to produce, marking an important step toward making cultivated meat more economically viable.

Figure 3. The first cultivated burger before cooking (a) and after cooking in a bun (b). Sourced from Stephens & Ruivenkamp 2016.

In 2020, the cultivated meat industry reached a historic milestone with the first-ever legislative approval of a cultivated meat product. The regulatory green light was given to Eat Just in Singapore, making it the first country in the world to approve cultivated meat for human consumption. Shortly after, the first commercialization took place when a restaurant in Singapore began serving cultivated chicken to the public, marking a pivotal moment in the transition from research to real-world dining experiences. By 2023, Singapore was no longer alone in approving cultivated meat. The United States became the second country to permit its commercial sale. In June 2023, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) granted approval for UPSIDE Foods and Good Meat (a division of Eat Just) to sell cultivated chicken in the country. This approval followed an official statement by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 2022, which confirmed that cultivated meat was safe for human consumption.

The cultivated meat industry has rapidly evolved into a fast-growing sector at the intersection of biotechnology and food production. While initial breakthroughs were driven by academic research, much of the advanced work in the field has been, and continues to be, led by startups. Today, more than 100 companies worldwide are actively working to commercialize and scale cultivated meat production. Even traditional agricultural and food corporations have recognized the potential of this emerging industry and begun to invest. Companies such as JBS, one of the world’s largest meat producers, acquired a biotech firm in Spain for €100 million, while Cargill has invested in cultivated meat pioneers Aleph Farms and Memphis Meats (now UPSIDE Foods). Most of these companies focus on cultivated beef, followed by poultry, pork, seafood, and even exotic meats such as mammoth, kangaroo, and horse. Geographically, the majority of cultivated meat companies are based in North America, followed by Asia and Europe. As the industry advances, it aims to address some of the most pressing global challenges related to livestock welfare, population growth, environmental impact, health concerns, and the sustainability of conventional industrial livestock farming. However, significant challenges remain, including high production costs, regulatory hurdles, consumer acceptance, and the need for large-scale infrastructure to make cultivated meat a viable alternative to conventional meat.

One of the major challenges in cultivated meat production has been the reliance on fetal bovine serum (FBS) as a nutrient-rich growth medium. However, significant efforts have been made to develop plant-based substitutes that can support cell growth while reducing costs, ethical concerns, and supply chain limitations. Researchers are also working on limiting the need for signaling molecules, which are essential for cell differentiation and growth but add to the complexity and expense of production. A promising approach is the development of cell lines that do not require external signaling molecules, making the production process more efficient and scalable. At the same time, achieving the texture and structure of conventional meat remains a key focus, with innovations in scaffolding, bioprinting, and biomaterials helping to replicate the fibrous quality of traditional muscle tissue. Despite these advancements, price remains a major barrier. While production costs have dropped significantly compared to the early prototypes, cultivated meat is still far from price parity with conventional meat. Ongoing research and investment aim to further optimize cell growth, nutrient efficiency, and bioreactor technology to bring costs down and make cultivated meat a viable alternative for mainstream consumers.

The meat industry is one of the largest global sectors, with over 350 million tonnes of meat produced annually worldwide. Cultivated meat has the potential to transform this industry by providing a more ethical and sustainable alternative. However, this transition will not be immediate or radical, as significant technological, economic, and infrastructural barriers remain. One of the primary challenges is the lack of industrial-scale production facilities capable of mass-producing cultivated meat. Currently, the global capacity for large-scale cultivated meat production is insufficient, and developing such infrastructure will take time and investment. A key long-term goal is for cultivated meat to meet at least 10% of the global meat demand in the coming decades. Achieving this will require scaling production technology, reducing the cost of growth media and equipment, optimizing cell lines for efficiency, and ensuring a stable supply of essential nutrients such as amino acids. As research and innovation continue, cultivated meat may play an increasingly important role in the future of sustainable food production.

Resources:

Arshad, M. S.; Javaid, M.; Sohaib, M.; Saeed, F.; Imran, A. Tissue Engineering Approaches to Develop Cultured Meat from Cells: a mini review. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 2017, 3,1, 1320814. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2017.1320814

Fraeye, I.; Kratka, M.; Vandenburgh, H.; Thorrez, L. Sensorial and Nutritional Aspects of Cultured Meat in Comparison to Traditional Meat: Much to Be Inferred. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2020, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.00035

Kirsch, M.; Morales-Dalmau, J.; Lavrentieva, A. Cultivated meat manufacturing: Technology, trends, and challenges. Engineering in Life Sciences, 2023, 23, e2300227. https://doi.org/10.1002/elsc.202300227

Kumar, P.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, S.; Mehta, N.; Verma, A. K.; Chemmalar, S.; Sazili, A. Q. In-vitro meat: a promising solution for sustainability of meat sector. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 2021, 63, 4, 693-724. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2021.e85

Lee, S. Y.; Lee, D. Y.; Yun, S. H.; Lee, J.; Mariano, E. J.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.; Han, D.; Kim, J. S.; Hur, S. J. Current technology and industrialization status of cell-cultivated meat. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 2024, 66, 1, 1-30. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2023.e107

Rubio, N. R.; Xiang, N.; Kaplan, D. L. Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production. Nature communications, 2020, 11, 6276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20061-y

Simonsen, R. Eating for the Future:Veganism and the Challenge of In Vitro Meat. In Biopolitics and Utopia, 2015, Chapter 7, 167-109. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137514752_8

Song, H.; Chen, P.; Sun, Y.; Sheng, J.; Zhou, L. Knowledge Maps and Emerging Trends in Cell-Cultured Meat since the 21st Century Research: Based on Different National Perspectives of Spatial-Temporal Analysis. Foods, 2024, 13, 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13132070

Stephens, N.; Ruivenkamp, M. Promise and Ontological Ambiguity in the In vitro Meat Imagescape: From Laboratory Myotubes to the Cultured Burger. Science as Culture, 2016, 25, 3, 327-355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2016.1171836

Treich, N. Cultured Meat: Promises and Challenges. Environmental and Resource Economics, 2021, 79, 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00551-3