Traditional livestock farming has so far been able to meet the global demand for meat, but the expectations regarding efficiency, sustainability, and responsible practices are continuously evolving. As a result, alternative methods of meat production, such as cultivated meat, have emerged as potential solutions to some of the technical and environmental challenges associated with conventional farming. Today’s livestock production is characterized by various intensification strategies aimed at increasing output. Systems such as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are widespread. These intensive farming conditions, along with other factors, are designed to maximize meat production to meet the ever-growing demand. In this context, consumers often assume that national authorities guarantee a high level of protection and fairness in food production. However, the situation is more complex. One of the fundamental challenges lies in the lack of a single, universally accepted definition of what constitutes “meat,” which leads to ambiguity in labeling and regulation.

For example, the most comprehensive definition of meat in Europe is found in the EU meat hygiene law. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and the Council of 29 April 2004, which lays down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin, defines meat as all edible parts of the specified animals, including blood and organs. In contrast, in the United States, the definition of meat is more detailed and established by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). According to the Code of Federal Regulations (9 CFR §301.2), meat includes not only skeletal muscle but also organs such as the tongue, diaphragm, heart, and esophagus, along with associated tissues like fat, bone, skin, sinew, nerves, and blood vessels, provided they are not separated from the muscle during processing. While the American definition is more precise, both definitions include elements that many consumers would not typically consider as meat. Consumers often envision meat as clean cuts of muscle tissue, yet legal definitions allow for the inclusion of parts such as sinew, nerves, and even bones, which may not align with their expectations. This discrepancy between regulatory definitions and consumer perceptions raises important questions about labeling transparency and whether current standards truly reflect what people believe they are buying.

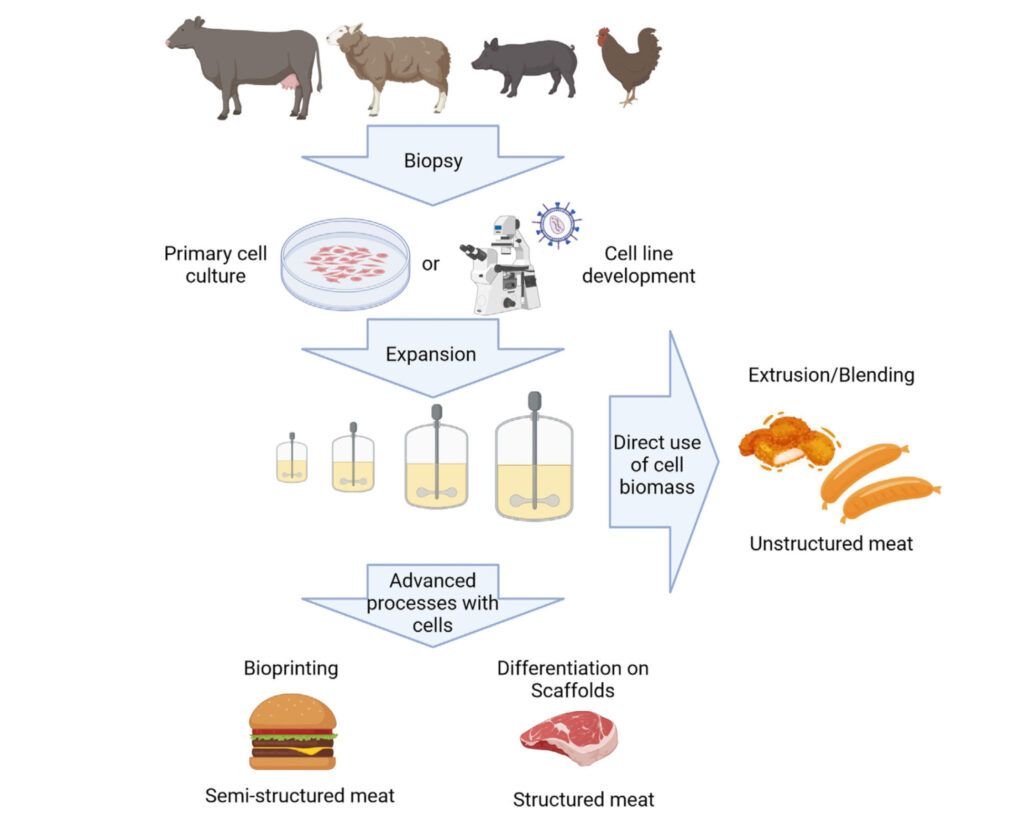

Cultivated meat represents a fundamentally different approach to meat production. Unlike conventional meat, where an entire animal must be raised, only for many of its parts to go unused, cultivated meat is designed to produce only the specific parts that are valuable for consumption. This makes the process significantly more efficient, reducing waste and optimizing resource utilization. The production of cultivated meat relies on advanced cell engineering technologies. The process of cell cultivation is illustrated in Figure 1. The first step in cultivated meat production is selecting an appropriate cell line, a decision influenced by various factors, including the chosen animal species and the desired final product. These cells can be isolated either from the muscle tissue of slaughtered livestock or obtained through biopsies from live donor animals. The condition of these extracted cells can vary depending on the health and state of the donor animal. Once the sample is collected, the specific cell type is isolated and used for further cultivation. In addition to cultivating primary cells directly, another approach involves developing a stable cell line first. By establishing a dedicated cell line, researchers can ensure consistency, optimize growth conditions, and create a reliable and scalable source of cells for cultivated meat production.

Figure 1. The process of cultivation. Sourced from Kirsch et al. 2023.

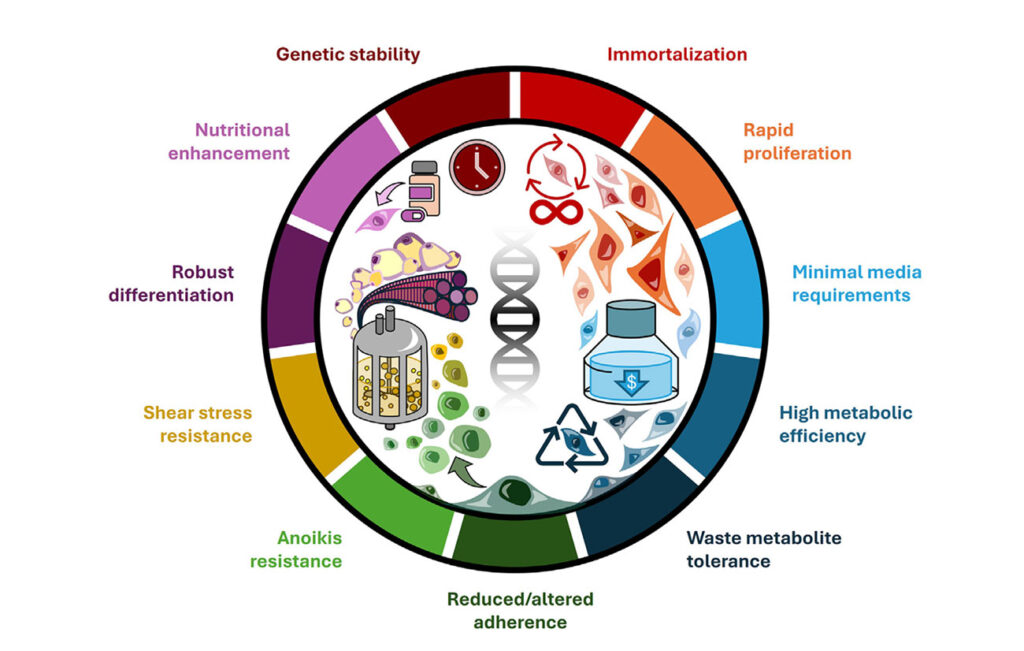

The selected cells can range from different types of stem cells to fully differentiated somatic cells. The primary objective is to identify or modify cells that can proliferate rapidly, thereby generating a large quantity of cellular biomass. There are three main strategies for obtaining a sufficient number of cells: direct isolation of a large cell population, cell immortalization, and the selection of fast-growing cells. Direct isolation, while providing an initial supply, does not solve the issue of limited proliferative capacity, as these cells naturally stop dividing after a certain number of replications. The second approach is creating immortalized cell lines, which involves extending the lifespan of cells indefinitely. Several mechanisms can be used for this process, such as introducing the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene into the genome, which prevents cellular aging. However, this method results in genetic modifications, which are not widely accepted in some regions due to regulatory and ethical concerns. Another method of immortalization involves exposing cells to chemical carcinogens or ionizing radiation. While this approach does not introduce foreign genes, it is less controlled than genetic modifications and may result in unpredictable cellular changes. Spontaneous immortalization can also occur, but the probability is extremely low. The third and most promising approach is selecting fast-growing cells. Stem cells naturally exhibit a high proliferation rate, making them well-suited for long-term cultivation. The most commonly used stem cells in cultivated meat research include embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and satellite muscle cells (SMCs). A successful cultivated meat production process relies on selecting and engineering cell lines with desirable traits (see Figure 2.). The image below illustrates key cellular phenotypes essential for industrial-scale bioprocessing, including genetic stability, rapid proliferation, metabolic efficiency, and differentiation capacity.

Figure 2. Desirable traits of cultivated cells. Sourced from Riquelme-Guzmán et al. 2024.

While ESCs are considered to have the highest efficiency in cultivated meat production due to their robust proliferation and differentiation capabilities, their use raises ethical concerns regarding animal welfare. Additionally, legal challenges are expected when considering the consumption of cultivated meat derived from ESCs. To address these ethical and regulatory challenges, researchers have turned to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which exhibit similar properties to embryonic stem cells but are generated through artificial reprogramming. iPSCs offer a promising alternative, as they circumvent the ethical dilemmas associated with ESCs. Another widely used cell type in cultivated meat production is muscle satellite cells. These cells exist between myofibroblasts and the basal membrane and belong to the category of adult stem cells. Due to their multipotency, muscle satellite cells can differentiate into muscle cells, adipocytes, osteocytes, or myocytes. They are particularly advantageous for cultivated meat production because of their natural regenerative ability, which allows them to efficiently develop into myotubes and mature myofibrils, forming structured muscle tissue. Their regenerative properties and ease of differentiation make them one of the most practical choices for large-scale cultivated meat production.

The cells are then cultivated in a specialized nutrient-rich medium, the composition of which depends on the selected cell line. The basic medium typically consists of glucose, glutamine, amino acids, vitamins, inorganic salts, signaling molecules such as growth factors, and buffers. The composition of the medium is crucial for inducing the desired cellular state, including proliferation, adhesion, and differentiation, as well as for supporting cell survival. One of the key components of the medium is glucose, which serves as an energy source for cell cultures. Amino acids play a fundamental role in protein synthesis and the formation of low-molecular-weight compounds. Among these, L-glutamine is particularly vital in cell culture as it contributes significantly to protein biomass production and is easily transported into cells. As an essential amino acid, glutamine can be metabolized as an alternative energy source during periods of rapid cell proliferation, serving as a precursor for carbon- and nitrogen-containing biomolecules such as amino acids and nucleotides. Inorganic salts play a critical role in maintaining osmotic pressure within cells and act as essential cofactors for enzymes, receptors, and extracellular matrix proteins. Vitamins are another essential component, supporting cell growth and maintenance.

In the early stages of cultivated meat technology, fetal bovine serum (FBS) was widely used as a key supplement. It is derived from the blood of bovine fetuses extracted from the uterus of pregnant cows. It contains essential nutrients, growth factors, and hormones required for cell cultures and is widely utilized due to its relatively low risk of immune rejection. Additionally, FBS provides binding factors, macronutrients, micronutrients, growth regulators, and protective elements that promote rapid cell turnover. However, despite its advantages, FBS also poses ethical concerns, carries the risk of contamination with viruses or prions, and contributes to high production costs, making large-scale manufacturing more challenging. As a result, many companies in the cultivated meat industry are actively working to develop serum-free alternatives. Serum-free media typically consist of base cultures supplemented with chemically defined compounds or growth factors. These alternatives may include added hormones, recombinant proteins, and synthetic growth factors.

Bioreactors play a crucial role in the cultivation process, providing a controlled environment for cell proliferation and differentiation. Bioreactors can be classified into three types: batch, fed-batch, and continuous. This classification is based on how the medium is introduced into the main vessel of the bioreactor. They come in various types and shapes, such as rotary and stirred-tank bioreactors, each designed to maintain optimal conditions for cell growth. Within the bioreactor, essential factors like nutrient supply, oxygenation, and low shear stress are carefully regulated to support efficient cell expansion. Cells within the culture are supplied with nutrients through regular media exchange, and when they proliferate beyond a certain density, they are subcultivated into new vessels. The frequency of media exchange and subcultivation varies depending on the type of cells being cultivated. In general, seed culture propagation is determined based on the growth curve of the specific cell line, ensuring optimal conditions for large-scale cultivated meat production. The consistent and scalable production of cultivated meat relies on a stable environment, which bioreactors provide by automating key parameters. This is essential, as various types of meat cells, such as myocytes, are anchorage dependent and require a surface for proper proliferation and differentiation.

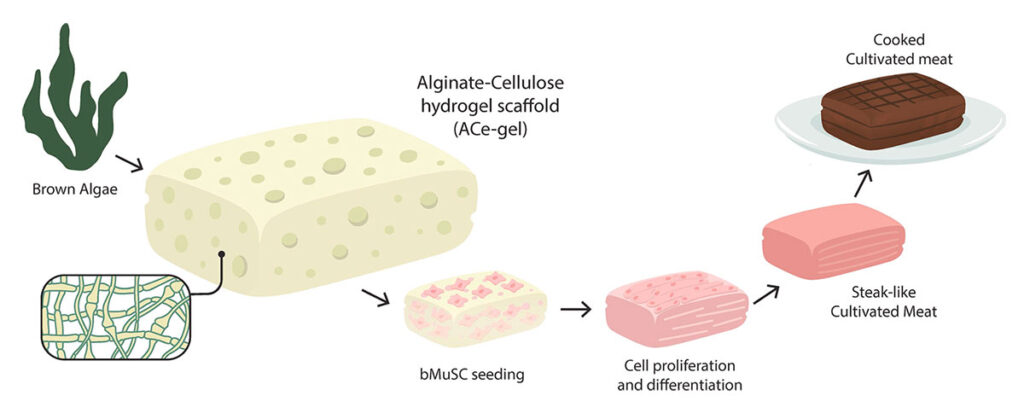

The next step is the effort to create a structured texture. Currently, this remains one of the major challenges in cultivated meat production. Research is progressing in two main directions: scaffolds (see Figure 3.) and microcarriers. The scaffolds and supporting materials used must be edible and can be derived from non-animal sources. A recent breakthrough in scaffold development involved the extrusion of hemp, corn, and pea protein fibers to create a structural framework for cultivated meat. However, a major drawback of this method is that it cannot be used in a suspension bioreactor, leading to the development of microcarriers as a potential solution. Microcarriers are made from various materials such as dextran, gelatin, collagen, and cellulose. These microcarriers are mixed with cultivation media and cells inside a 3D bioreactor, forming a complex where cells attach and proliferate. However, one challenge with microcarrier-based cultivation is that cell activity and proliferation can be inhibited due to shear stress generated by the continuous agitation of the cell-microcarrier complex. As with scaffolds, it is crucial to develop microcarriers from materials that can be immediately consumed without requiring separation from the cultivated cells. Scaffolds and microcarriers can serve as key stimuli for cell differentiation through mechanical stimulation. However, differentiation can also be triggered by removing growth factors from the cultivation medium or introducing proteins that promote differentiation.

Figure 3. The process of structuring cultivated meat using scaffolding technology. Sourced from Lee et al. 2024a.

Just like in a living organism, cultivated cells follow fundamental biological principles, which can be framed as three cellular laws inspired by Asimov’s Laws of Robotics. First, a cell must ensure the survival of the organism it is part of. In cultivated meat production, this means recreating an environment that mimics the natural conditions of a living body, providing cells with the necessary nutrients, oxygen, and growth signals to maintain their function. Second, a cell must perform its biological role and respond to the organism’s signals. In their natural state, cells receive biochemical cues that regulate their behavior: when to multiply, differentiate, or remain quiescent. In the cultivation process, these signals are artificially introduced, often through growth factors that stimulate proliferation and differentiation. Traditionally, FBS has been used as a nutrient-rich supplement to support cell growth. Derived from the blood of bovine fetuses during slaughter, FBS contains essential proteins, hormones, and growth factors that facilitate cell survival and proliferation. However, its use raises ethical concerns, variability issues, and risks of contamination, which is why the industry is shifting towards serum-free and chemically defined media. Finally, a cell must strive for its own survival, as long as this does not conflict with the first two laws. Even in a controlled environment, cells have inherent survival mechanisms, including responses to stress and damage. The challenge of cultivated meat production lies in balancing these biological imperatives with efficient and scalable cultivation processes, ensuring that cells not only survive but also thrive in a way that enables large-scale, ethical, and sustainable meat production.

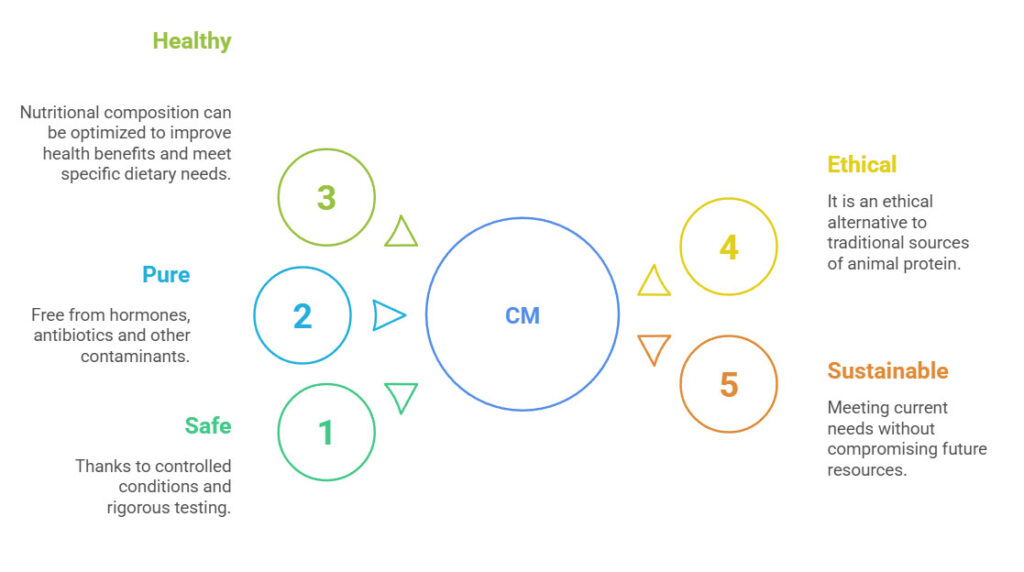

One of the key advantages (Figure 4.) of cultivated meat is its highly controlled production process, which ensures safety, purity, and consistency. Unlike conventional meat production, where animals are exposed to various environmental factors, cultivated meat is grown in a sterile environment, eliminating the need for hormones, antibiotics, or other additives. This controlled approach also significantly reduces the risk of bacterial contamination and foodborne illnesses, as pathogens such as Salmonella or E. coli are not introduced into the system. Moreover, advancements in genetic engineering (GMO technologies) offer the possibility of removing harmful or undesirable components from meat. This could include eliminating allergens, toxins, or disease-related compounds naturally present in conventional meat, further enhancing consumer safety. Lastly, the standardized nature of the process guarantees consistent quality. Every batch of cultivated meat can be tailored for optimal nutritional profile, texture, and taste, ensuring a product free from variability caused by factors like animal diet, stress, or genetics. This level of precision makes cultivated meat a predictable and reliable food source.

Figure 4. Advantages of cultivated meat (CM).

Resources:

European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 Laying Down Specific Hygiene Rules for Food of Animal Origin. Official Journal of the European Union, 2024, 139, 55-205.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32004R0853

Giglio, F.; Scieuzo, C.; Ouazri, S.; Pucciarelli, V.; Ianniciello, D.; Letcher, S.; Salvia, R.; Laginestra, A.; Kaplan, D. L.; Falabella, P. A Glance into the Near Future: Cultivated Meat from Mammalian and Insect Cells. Small Science, 2024, 4, 10, 2400122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smsc.202400122

Kirsch, M.; Morales-Dalmau, J.; Lavrentieva, A. Cultivated meat manufacturing: Technology, trends, and challenges. Engineering in Life Sciences, 2023, 23, e2300227. https://doi.org/10.1002/elsc.202300227

Lautenschlaeger, R.; Upmann, M. How meat is defined in the European Union and in Germany. International Perspectives, 2017, 7, 4, 57-59. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2017.0446

Lee, H.; Kim, D.; Choi, K. H.; Lee, S.; Jo, M.; Chun, S.-Y.; Son, Y.; Lee, J. H.; Kim, K.; Lee, T.; Keum, J.; Yoon, M.; Cha, H. J.; Rho, S.; Cho, S. C.; Lee, Y.-S. Animal-free scaffold from brown algae provides a three-dimensional cell growth and differentiation environment for steak-like cultivated meat. Food Hydrocolloids, 2024a, 152, 109944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.109944

Lee, S. Y.; Lee, D. Y.; Yun, S. H.; Lee, J.; Mariano, E. J.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.; Han, D.; Kim, J. S.; Hur, S. J. Current technology and industrialization status of cell-cultivated meat. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 2024b, 66, 1, 1-30. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2023.e107

Post, M. J.; Levenberg, S.; Kaplan, D. L.; Genovese, N.; Fu, J.; Bryant, Ch. J.; Negowetti, N.; Verzijden, K.; Moutsatsou, P. Scientific, sustainability and regulatory challenges of cultured meat. Nature Foods, 2020, 1, 403-415. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0112-z

Rodriguez, S. S. Q.; Leite, A.; Vasconcelos, L., Teixeira, A. Exploring the Nexus of Feeding and Processing: Implications for Meat Quality and Sensory Perception. Foods, 2024, 13, 3642. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13223642

Riquelme-Guzmán, C.; Stout, A. J.; Kaplan, D.L.; Flack, J. E. Unlocking the potential of cultivated meat through cell line engineering. Iscience, 2024, 27, 10, 110877

Rubio, N. R.; Xiang, N.; Kaplan, D. L. Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production. Nature Communications, 2020, 11, 6276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20061-y

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service. Title 9 – Animals and Animal Products, Chapter III – Food Safety and Inspection Service, Department of Agriculture, Part 301 – Terminology; Adulteration and Misbranding, §301.2 – Definitions. Code of Federal Regulations, 2024. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/chapter-III/part-301

Weber, T.; Wirhs, F.; Brakenbusch, N.; van der Valk, J. Reply to Comment “Animal Welfare and Ethics in the Collection of Fetal Blood for the Production of Fetal Bovine Serum”. ALTEX – Alternatives to Animal Experimentation, 2021, 38, 2,. 324–326. https://doi.org/10.14573/altex.2103191