Proteins are essential macronutrients that play a vital role in the growth, repair, and maintenance of the human body. Alongside carbohydrates and lipids, proteins can also serve as a source of energy in the diet when other energy sources are insufficient. Given their biological importance, evaluating the protein quality of food is a key aspect of nutritional science and food regulation. Protein quality can be assessed through various parameters, including the total protein content, the profile and balance of essential amino acids, the protein digestibility and bioavailability of amino acids. Accurate quantification of protein in food and food raw materials is crucial for ensuring both nutritional quality and regulatory compliance. Several analytical methods are currently used to measure protein content; however, these methods often yield varying results due to differences in their underlying principles. The most commonly applied techniques today, such as the Kjeldahl and Dumas methods, determine protein concentration indirectly by measuring the total nitrogen content of the sample. While useful, these methods lack analytical selectivity, as they cannot differentiate between nitrogen derived from protein and nitrogen originating from non-protein sources. This can lead to inaccuracies, especially in foods containing significant amounts of non-protein nitrogenous compounds. Understanding the limitations and applications of these methods is essential not only for accurate nutritional labeling but also for the broader evaluation of food quality. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the assessment of protein quality should go beyond total content and also consider the amino acid composition, the bioavailability of indispensable amino acids, and the protein’s ability to support optimal physiological function.

First developed in 1883 by Johan Kjeldahl, the Kjeldahl method remains one of the most widely used analytical techniques for determining total nitrogen content in organic substances. Although it has been significantly refined over the past century, its fundamental principles have stayed the same and it is still considered the international reference method for the determination of crude protein in food and industrial applications. The method is based on the assumption that most nitrogen in food is associated with amino acids and, by extension, with proteins. The procedure consists of three main steps. In the digestion phase, organic nitrogen is broken down by boiling the sample in concentrated sulfuric acid, forming ammonium sulfate. This is followed by distillation, where an excess base is added to convert ammonium ions (NH₄⁺) into ammonia gas (NH₃), which is then distilled and captured in a receiving solution. Finally, the amount of ammonia is quantified via titration, providing a measure of the total nitrogen present in the sample.

To convert the measured nitrogen content to an estimate of total protein, a conversion factor, typically 6.25, is applied. This value originates from the 19th century and is based on the assumption that proteins contain 16% nitrogen. However, this generalization overlooks the fact that the nitrogen content of proteins can vary significantly, depending on their amino acid composition. In reality, protein nitrogen content ranges from approximately 13% to 19%, and using a fixed factor of 6.25 can lead to systematic over- or underestimation of true protein content. Errors of 15–20% are not uncommon. Moreover, the Kjeldahl method lacks the ability to distinguish between protein nitrogen and non-protein nitrogen. Foods often contain various nitrogenous compounds such as nucleic acids, amines, nitrates, alkaloids, urea, and certain vitamins, all of which can inflate the apparent protein content. For instance, mushrooms have a high and variable content of non-protein nitrogen from compounds like chitin and chitosan, which can lead to overestimations of protein content by up to 23% when compared to amino acid-based methods. In one study, the protein content of certain foods was overestimated by 44–71% using the Kjeldahl method, highlighting its limitations when used without complementary techniques. Despite its shortcomings, the Kjeldahl method remains a standard in food industry and regulatory laboratories due to its robustness, reproducibility, and long-standing validation history. However, for applications requiring precise nutritional profiling, especially in protein quality assessment, more selective and modern analytical methods may be necessary.

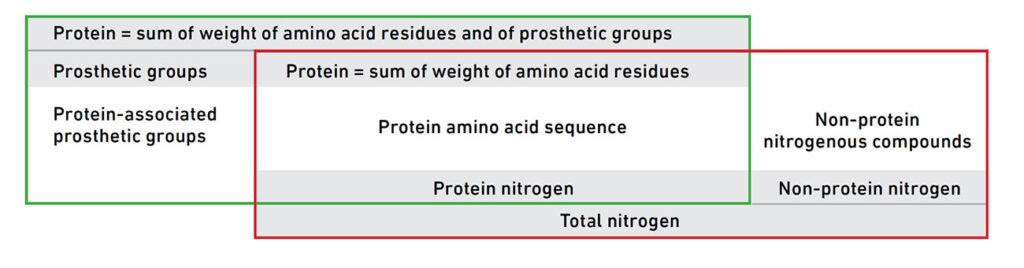

Another widely used method for determining protein content is the Dumas method, which, like the Kjeldahl method, is based on the measurement of total nitrogen. First developed in the 19th century, the Dumas method has gained popularity as a modern alternative, primarily due to its faster analysis time, simplicity, and the fact that it avoids the use of hazardous chemicals like concentrated sulfuric acid. In the Dumas process, a food sample is combusted at high temperatures in the presence of oxygen, converting all nitrogen-containing compounds into nitrogen gas (N₂). The resulting gas is then measured, and the nitrogen content is converted into a crude protein estimate using a similar conversion factor as in the Kjeldahl method (most often 6.25). In contrast to Kjeldahl, the Dumas method does not involve digestion or titration, making it easier to automate and more environmentally friendly. However, while the Dumas method improves efficiency and safety, it does not enhance the analytical selectivity for true protein content. Just like Kjeldahl, it cannot distinguish between nitrogen from protein and nitrogen from non-protein sources such as nucleic acids, urea, or nitrates. As a result, the Dumas method is equally susceptible to overestimation and adulteration, particularly in complex or plant-based food matrices where non-protein nitrogen can be present in significant quantities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A conceptual comparison between total nitrogen and actual protein content. The red box indicates the components measured by nitrogen-based methods (Kjeldahl or Dumas), which include both protein and non-protein nitrogen. The green box illustrates the more accurate biochemical definition of protein based on amino acid residues and associated prosthetic groups. Sourced from World Health Organization, 2019.

Historically, attempts were made in the 1870s to refine protein quantification by separating so-called “true protein” from other nitrogenous substances. However, interest in these more selective techniques declined after it was discovered that some non-protein nitrogen compounds could provide nutritional benefits, leading to the continued dominance of total nitrogen-based methods like Kjeldahl and Dumas. In summary, while the Dumas method offers practical advantages in terms of speed and safety, it shares the same fundamental limitations as the Kjeldahl method. Neither approach provides a complete picture of protein quality or biological value. Both methods measure only the total nitrogen content, which is an imperfect proxy for true dietary protein.

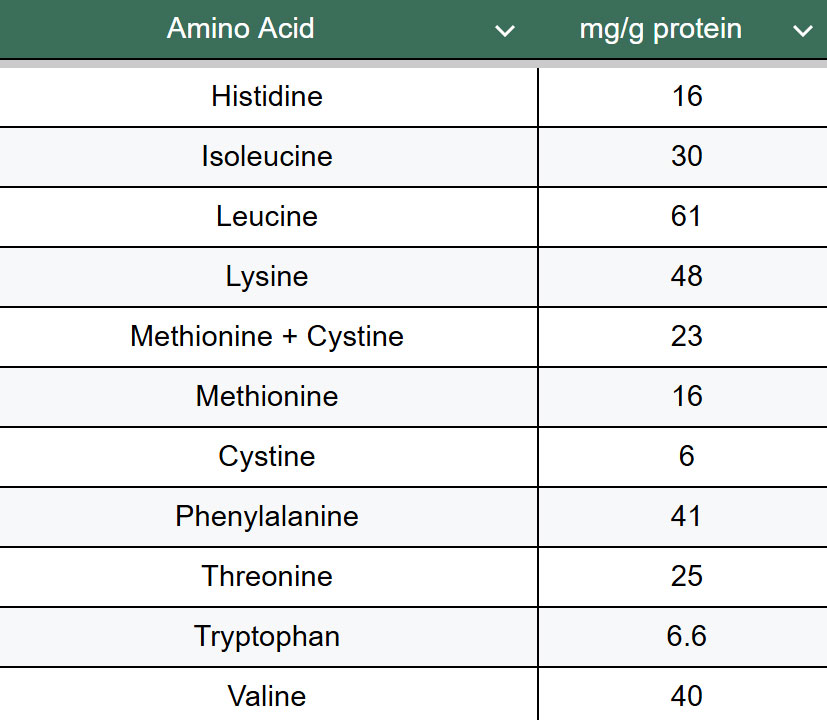

A more specific and informative method for evaluating protein content is amino acid analysis, first developed around 1950. This method provides precise information about the amino acid composition of a given food sample. Amino acid analysis involves three primary steps. 1. Protein hydrolysis to release individual amino acids. 2. Separation of the amino acids via chromatography. 3. Detection and quantification of each amino acid. Although this method is more costly, technically demanding, and time-consuming than nitrogen-based methods, it offers a significant advantage of an exact breakdown of amino acid content. This is essential for assessing the nutritional quality of proteins, especially in the context of essential amino acids. The body can only use essential amino acids for protein synthesis to the extent that the most limiting amino acid is available (see Table 1 for dietary amino acid requirements). If one essential amino acid is lacking, the excess of others cannot be fully utilized and is excreted. Therefore, improving the content of the limiting amino acid in a food can enhance the utilization of all amino acids. Just as there are daily recommendations for total protein intake, there are also guidelines for individual amino acid requirements, which are especially relevant for formulating balanced diets and evaluating the nutritional adequacy of novel protein sources.

Table 1. Dietary requirements for amino acids in adults. The average amino acid requirements were determined based on the minimum recommended protein intake (0.66 g per kilogram of body weight), which corresponds to 105 mg of nitrogen. This value serves as the basis for calculating the recommended intake of individual essential amino acids. Data sourced from FAO 2013 and FAO/WHO/UNU 2007.

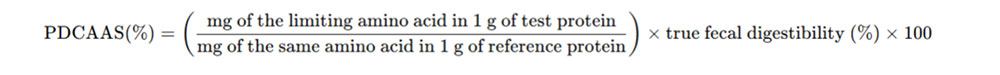

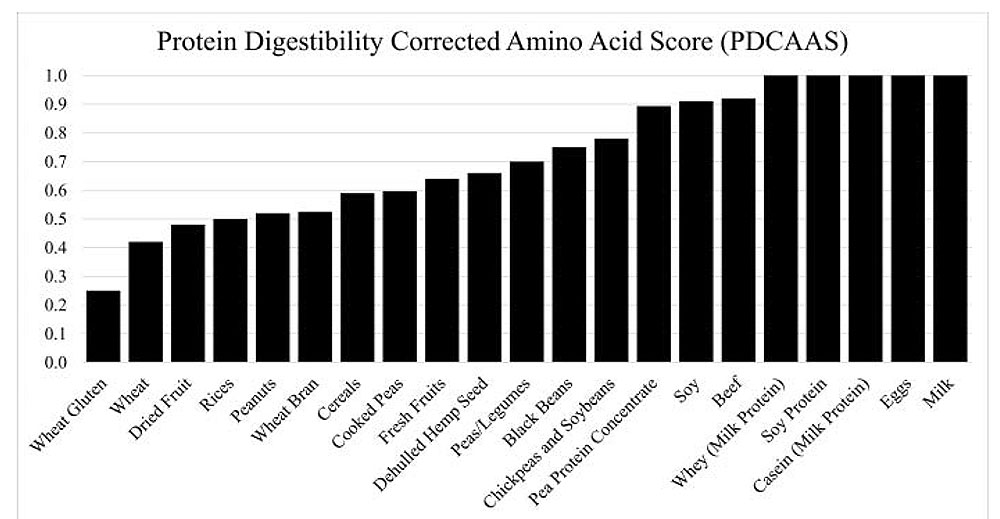

To provide a standardized metric for evaluating protein quality, the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) was introduced by the FAO/WHO in 1989 and adopted by the U.S. FDA in 1993. This method estimates the bioavailability of essential amino acids in a given protein relative to a reference protein. PDCAAS is calculated by multiplying the amino acid score (determined by the concentration of the first limiting indispensable amino acid in the test protein divided by its concentration in a reference pattern) by the true fecal crude protein digestibility factor. Due to its speed, low cost, and simplicity, PDCAAS has become a go-to method for protein quality assessment in the diets of healthy individuals and is used widely for nutrition labeling (see Figure 2. for PDCAAS of selected food sources). However, several limitations have been noted. Values are truncated to 1.0. Any values above 1.0 are capped, based on the assumption that excess amino acids offer no additional physiological benefit. Reference scoring patterns may not fully reflect accurate amino acid requirements across all age groups and physiological states. Fecal digestibility does not account for digestibility at the ileum, where most amino acid absorption occurs, leading to possible overestimation of protein bioavailability. The crude protein digestibility factor used is based on total nitrogen digestibility and does not reflect the individual digestibility of specific amino acids, which can vary considerably. These limitations suggest that while PDCAAS is a practical and accessible tool, it may not fully capture the true nutritional quality of a protein source. More accurate methods are therefore gaining attention for their ability to address some of PDCAAS’s shortcomings.

Figure 2. Protein Digestability Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) for selected food sources. Sourced from Huang et al. 2017.

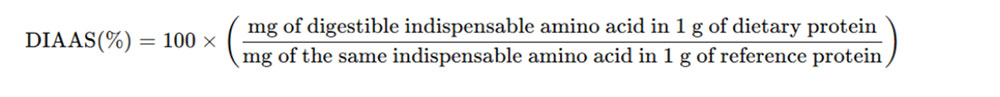

Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) is a more accurate and scientifically advanced method for assessing protein quality, recommended by the FAO as a replacement for PDCAAS. Unlike PDCAAS, which relies on total nitrogen and fecal digestibility, DIAAS is based on true ileal digestibility of individual essential amino acids. This gives a more precise picture of actual amino acid absorption. One key advantage of DIAAS is that values are not truncated at 1.0, allowing differentiation between proteins that exceed requirements and those that merely meet them. This is especially useful for identifying excellent or very good sources of protein. Despite its accuracy, DIAAS remains technically demanding and costly, limiting its widespread use. Nonetheless, it represents the gold standard in protein quality assessment and continues to gain traction as the food industry moves toward more precise and meaningful labeling of nutritional content.

Multiple methods exist for determining protein content in food, each with its own advantages and limitations. While nitrogen-based methods like Kjeldahl and Dumas remain the most commonly used due to their speed and simplicity, they do not differentiate between protein and non-protein nitrogen sources, nor do they provide insight into amino acid composition or bioavailability. This lack of specificity can lead to misleading nutritional labels and, in extreme cases, food fraud. Notable incidents include the 2007–2008 contamination of pet food and infant formula with melamine and other nitrogen-rich compounds, which were added to falsely elevate protein readings and led to illness and death. Emerging protein sources such as insects present unique challenges. Insects contain high levels of chitin, a nitrogen-rich, indigestible polysaccharide, which can also lead to overestimation of protein content if analyzed using traditional nitrogen-based methods. Given the variability in chitin content across insect species and life stages, more accurate approaches such as species-specific conversion factors or amino acid analysis are essential to assess their true nutritional value.

Ultimately, amino acid analysis should be considered the preferred method for food protein determination. It enables not only accurate quantification of total protein but also evaluation of limiting amino acids, which is critical for preventing deficiencies and ensuring nutritional adequacy. While cost and complexity remain barriers, investment in precise and reliable protein analysis is vital for both food producers and consumers. Reliable and standardized protein determination methods help ensure fair trade, consumer safety, and the nutritional integrity of our food system. Among current methods, DIAAS stands out scientifically as the most accurate, as it reflects the true digestibility of individual amino acids in the small intestine. However, even DIAAS may underestimate amino acid availability for protein synthesis. As research continues, a combination of approaches, including amino acid profiling and digestibility studies, may offer the best strategy to evaluate protein sources and guide both dietary recommendations and food innovation.

Resources:

Brestenský, M.; Nitrayová, S.; Patráš, P.; Nitray, J. Dietary Requirements for Proteins and Amino Acids in Human Nutrition. Current Nutrition & Food Science, 2018, 14, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573401314666180507123506

Food and Agricultural Organization. Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition. Report of an FAQ Expert Consultation. FAO, 2013. https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/53cf3d0a-1db2-4667-823a-e9d73278efe9

Food and Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization/UNU. Protein and amino acid requirements for human nutrition. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert consultation. 2007. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43411/WHO_TRS_935_eng.pdf

Hayes, M. Measuring Protein Content in Food: An Overview of Methods. Foods, 2020, 9, 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9101340

Huang, S.; Wang, L. M.; Sivendiran, T.; Bohrer, B. Review: Amino acid concentration of high protein food products and an overview of the current methods used to determine protein quality. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2017, 58, 15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2017.1396202

Chromý, V.; Vinklárková, B.; Šprongl, L.; Bittová, M. The Kjeldahl Method as a Primary Reference Procedure for Total Protein in Certified Reference Materials Used in Clinical Chemistry. I. A Review of Kjeldahl Methods Adopted by Laboratory Medicine. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry, 2015, 45, 2, 106-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2014.892820

Jonas-Levi, A.; Martinez, J.-J. I. The high level of protein content reported in insects for food and feed is overestimated. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2017, 62, 184-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2017.06.004

Mæhre, H. K.; Dalheim, L.; Edvinsen, G. K.; Elvevoll, E. O.; Jensen, I.-J. Protein Determination—Method Matters. Foods, 2018, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7010005

Mansilla, W. D.; Marinangeli, Ch. P. F.; Cargo-Froom, C.; Franczyk, A.; House, J. D.; Elango, R.; Columbus, D. A.; Kiarie, E.; Rogers, M.; Shoveller, A. K. Comparison of methodologies used to define the protein quality of human foods and support regulatory claims. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 2020, 45, 9, 917-926. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2019-0757

Moore, J. C.; DeVries, J. W.; Lipp, M.; Griffiths, J. C.; Abernethy, D. R. Total Protein Methods and Their Potential Utility to Reduce the Risk of Food Protein Adulteration. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2010, 9, 330-357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00114.x

Otter, D. E. Standardised methods for amino acid analysis of food. British Journal of Nutrition, 2012, 108, S230-S237. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512002486

World Health Organization. Nitrogen and protein content measurement and nitrogen to protein conversion factors for dairy and soy protein-based foods: a systematic review and modelling analysis. WHO, 2019. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331206/9789241516983-eng.pdf