Meat has played a crucial role in human nutrition for millions of years, providing essential proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals that have significantly influenced our biological and cognitive development. Its consumption is believed to have been a key driver of human evolution, particularly in the development of a larger and more complex brain. Meat offers a highly concentrated source of energy and essential nutrients, including vitamin B12, heme iron, and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, which are vital for brain function and overall health. The shift from a predominantly plant-based diet to one that incorporated meat allowed early humans to increase their caloric intake and reduce the time spent foraging, enabling the development of tool-making, social cooperation, and complex cultural behaviors. While meat has been a fundamental part of the human diet throughout history, its definition in modern food regulation is not always entirely precise. Under European regulations, it refers to the edible parts of carcasses derived from domestic ungulates (such as cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats), poultry, lagomorphs (rabbits and hares), wild game, and farmed game. This legal framework provides guidance for food labeling and industry standards, but the broad scope of the definition means that not all meat products are composed solely of muscle tissue.

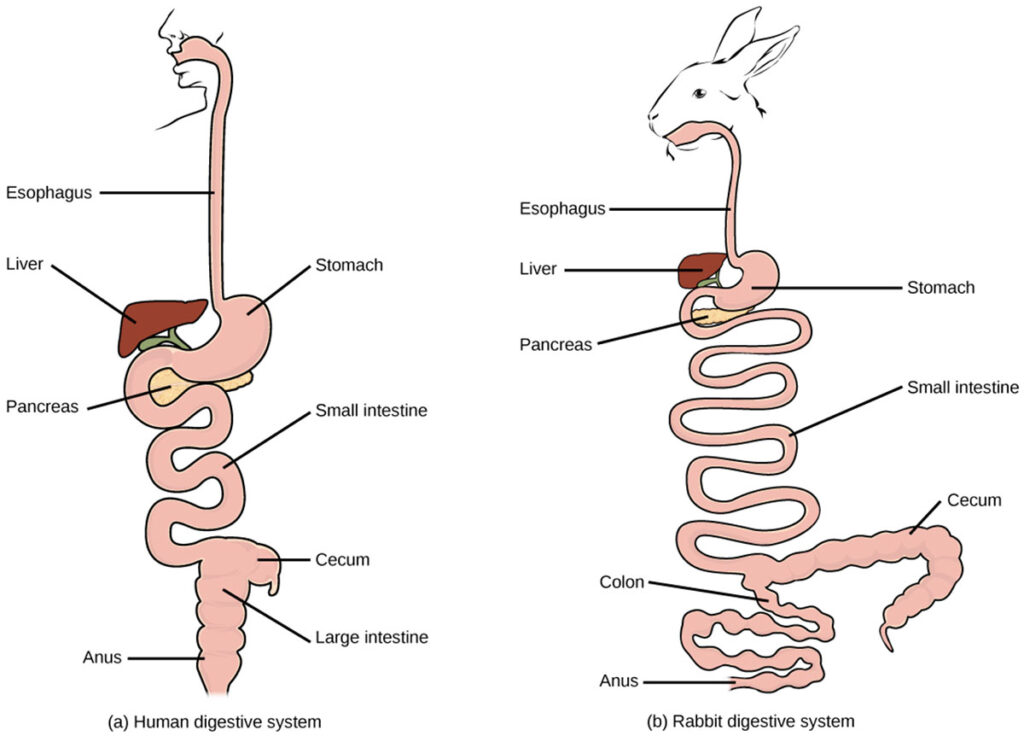

From a biological perspective, humans have evolved as omnivores, with a digestive system adapted for consuming a high-quality diet, with meat playing a predominant role in their evolutionary history. Unlike herbivores (see Figure 1.), humans have a simple stomach, an elongated small intestine, and a reduced cecum and colon, indicating a reliance on nutrient-dense foods such as meat rather than an exclusively plant-based diet. Meat is widely recognized as a high-quality source of essential nutrients, although its nutrient composition varies significantly depending on the animal species, feeding practices, and meat type. One of its most important contributions to human nutrition is protein, which plays a fundamental role in muscle development, enzyme function, and overall metabolic health. On average, meat contains around 22% protein, but this can range from as high as 34.5% in chicken breast to as low as 12.3% in duck meat.

Figure 1. Comparison of the human and rabbit digestive systems. The human digestive tract (a) represents an omnivorous diet with a simple stomach, elongated small intestine, and reduced cecum and colon. The rabbit digestive system (b), as an example of a herbivore, features an enlarged cecum and colon specialized for fermenting plant-based material. Sourced from OpenStax Biology (https://opentextbc.ca/biology/chapter/15-1-digestive-systems/).

At the core of every protein are amino acids, which serve as its fundamental building blocks. The nutritional value of any protein source depends on both the quantity and quality of the amino acids it contains, as well as whether it provides all the essential amino acids required by the human body. While 190 different amino acids have been identified in nature, only 20 are necessary for protein synthesis in humans. Of these, nine are classified as essential because they cannot be synthesized by the human body and must be obtained through diet. These include eight essential amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, valine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, and tryptophan), as well as histidine, which is considered an additional essential amino acid for children due to their higher metabolic demands. The effectiveness of a protein source is not solely determined by its amino acid composition but also by its digestibility, bioavailability, and bioactivity. Digestibility refers to how efficiently a protein is broken down into amino acids and absorbed in the digestive tract. Animal-based proteins, including meat, tend to have higher digestibility compared to plant proteins, as they lack antinutritional factors such as fiber, tannins, or phytic acid that can interfere with protein absorption. Bioavailability indicates the proportion of absorbed amino acids that can be utilized by the body for protein synthesis and other metabolic functions. Meat proteins are generally highly bioavailable, meaning the amino acids they provide can be efficiently used for tissue repair and growth. Bioactivity relates to the functional properties of proteins beyond basic nutrition, such as their role in immune modulation, hormone production, or muscle metabolism. Certain amino acids, like leucine, play a direct role in muscle protein synthesis, making them particularly important for growth and recovery. Meat is considered a complete protein source, meaning it provides all essential amino acids in appropriate proportions, along with high digestibility and bioavailability.

Fats are an integral component of meat, contributing both to its flavor and nutritional value. Beyond their role in enhancing taste and texture, fats are a dense source of metabolic energy and play a crucial part in cell membrane structure, hormone production, and immune function. The fat content in meat is highly variable, depending on factors such as species, origin, cut, and feeding system. While some meats, like chicken breast or lean beef, contain relatively low amounts of fat, others, such as pork belly or duck, are naturally higher in fat content. One of the most important aspects of dietary fat is the presence of essential fatty acids, particularly omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, which cannot be synthesized de novo by the human body and must be obtained from food. These fatty acids serve as carriers of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and play a vital role in immune response, brain function, and cardiovascular health. While some of omega-3 fatty acids are found in plant sources, the longer-chain forms, e.g., eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which are crucial for cell membrane integrity, tissue health, and brain function, are only available in marine organisms and land herbivores. These long-chain omega-3 fatty acids act as precursors to vasoactive and inflammatory-related eicosanoids, compounds that help regulate blood flow and inflammation. Increasing the omega-3 fatty acids content in meat through animal nutrition strategies has been an area of interest for improving the health benefits of meat consumption. However, daily intake of fats should not exceed 20-35% of total acquired energy.

Meat is also an important dietary source of essential vitamins, particularly fat-soluble (A, D, K) and B-complex vitamins, which play a crucial role in metabolism, immune function, and overall health. The bioavailability of these vitamins from animal-based sources is generally higher than from plant sources, making meat a valuable component of a balanced diet. B vitamins are essential for energy production, blood formation, and nervous system function. Among them, vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is particularly important, as it is required for normal blood function, nerve cell myelin synthesis, and DNA synthesis. B12 is also involved in the methylation of genetic material, a process crucial for cell regulation and gene expression. A deficiency in vitamin B12 can lead to megaloblastic anemia, characterized by large, immature red blood cells, and may result in elevated homocysteine levels, which are considered a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Another critical B vitamin found in meat is vitamin B9 (folate), which acts as a methyl donor crucial for fetal development and DNA methylation, a process believed to play a role in cancer prevention. Folate is particularly important during pregnancy, as inadequate levels are linked to neural tube defects in newborns.

Vitamin A is an essential nutrient for growth, development, and numerous physiological processes, including vision, immune response, cell differentiation, intercellular communication, and reproduction. It is found in both meat and vegetables, though the form found in animal products (retinol) is more readily absorbed than plant-based carotenoids. A deficiency in vitamin A (VAD) can cause severe night blindness (xerophthalmia), an eye disorder linked to extreme dryness, and is associated with reduced immune function, increasing susceptibility to infectious diseases.

Vitamin D plays a crucial role in musculoskeletal, immune, nervous, and cardiovascular system function. One of its primary roles is regulating calcium levels, which is essential for bone mineralization and preventing osteoporosis. Inadequate vitamin D levels lead to decreased calcium absorption, resulting in weakened bones and a higher risk of fractures. Beyond its skeletal functions, vitamin D is also involved in neurological health, with deficiencies linked to several neurological diseases. Its impact on the immune system is highly tissue-specific, influencing different cell types, organs, and systemic immune responses. Moreover, vitamin D is believed to regulate cardiovascular functions, contributing to overall heart health. The recommended daily intake, in the absence of sufficient sun exposure, is approximately 10–20 µg. However, studies indicate that the actual intake typically falls short, averaging only around 3–7 µg per day. Vitamin K2 also plays a vital role in bone metabolism and dental health, working in synergy with vitamin D to transport calcium from soft tissues and circulation into bones and teeth. This prevents arterial calcification while strengthening the skeletal system. Additionally, vitamin K2 has been associated with improved brain and kidney function, cancer prevention, and blood sugar regulation.

Essential minerals are more easily absorbed by the body from meat than from plant-based foods. This higher bioavailability of key minerals from meat sources is crucial for supporting physical and cognitive development, physiological functions, healthy blood, and a strong immune system. Iron is a critical mineral for oxygen transport, brain function, and immune support, but its absorption varies significantly depending on its source. Heme iron, found exclusively in animal-based foods, comes from hemoglobin and myoglobin and is highly bioavailable, with an absorption rate of 15 to 35%. In contrast, non-heme iron, which is found in plant sources, has much lower bioavailability (2 to 20%) and is more susceptible to absorption inhibitors like phytates and polyphenols. Meat’s superior absorption rate makes it a key part of iron-rich diets. Iron deficiency is a major risk factor for anemia, which can impair cognitive and motor development, particularly in infants and young children. Daily recommended iron intake for men is 8 mg and for women 18 mg (27 mg during pregnancy).

Zinc, like iron, is also more easily absorbed from animal-based foods because it is bound to protein, making it more readily available to the body. Zinc plays a crucial role in various bodily functions, including enzyme activity, cell division, gene expression, immune function, and reproductive health. Zinc deficiency can lead to a weakened immune system, oxidative stress, and genetic damage. The bioavailability of iron and zinc from ruminant meat is significantly higher (2 times for iron and 1.7 times for zinc) compared to plant-based sources like beans, lentils, and peas, emphasizing the superior absorption of these essential minerals from animal products.

Selenium, another crucial mineral found in meat, is a key component of selenoproteins, which act as antioxidants, promoting cardiovascular health and aiding in cancer prevention. Additionally, selenium plays a vital role in the activity of glutathione peroxidase, an enzyme essential for the body’s detoxification processes. Trace elements like copper, magnesium, cobalt, lead, chromium, and nickel, while only needed in small amounts, are essential for various metabolic and physiological processes. These processes include enzyme function, oxidative balance, and overall cellular health. Daily intake for adults is 55 µg.

Beyond its macronutrient and micronutrient content, meat is also a rich source of bioactive molecules that play crucial roles in healthy aging, immunity, muscle function, and the prevention of cardiovascular diseases and metabolic disorders. These compounds include taurine, creatine, carnosine, glutathione, anserine, and 4-hydroxyproline, all of which contribute to various physiological functions that support overall health. Taurine is found almost exclusively in meat products, as humans have a limited ability to synthesize it from its precursors, methionine and cysteine. This may be due to low levels of cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase, an enzyme required for taurine production. Newborn infants, in particular, have reduced taurine synthesis and must obtain it from dietary sources. Taurine exhibits strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, making it an important molecule for cardiovascular health and disease prevention. Creatine is an essential energy carrier in muscle cells, where it facilitates the rapid production of ATP, the body’s primary energy currency. It is naturally present in meat and plays a vital role in muscle performance, strength, and endurance. Supplementation with creatine has been shown to enhance physical performance and support muscle maintenance during aging. Carnosine is a dipeptide formed from the amino acid beta-alanine and functions as a potent antioxidant. It is particularly abundant in muscle and brain tissue, where it helps to buffer pH levels, reduce oxidative stress, and support muscle contraction and endurance. Glutathione is a powerful antioxidant that plays a key role in cellular detoxification and immune function. It helps to neutralize free radicals and supports the body’s natural defense mechanisms against oxidative damage.

Meat consumption has played a long and significant role in human evolution, potentially dating back to the earliest known anthropomorphic ancestor that lived 5 to 7 million years ago. Although direct evidence of early meat consumption is lacking, studies of our closest common ancestor with chimpanzees suggest that meat-eating has deep evolutionary roots. This dietary behavior likely originated before the evolution of anthropomorphic primates. The history of meat consumption can be divided into four key periods. In the earliest stage, our ancestors engaged in occasional hunting and possibly scavenging. Around 2 million years ago, the regular practice of hunting is believed to have begun, marking a shift in dietary patterns that provided early humans with a high-energy, nutrient-dense food source. The third major transition occurred about 10,000 years ago, when humans shifted from hunting and gathering to domesticated food sources, incorporating both animal and plant-based agriculture. Finally, the modern era of sustainable meat consumption emerged, particularly after World War II, when advancements in livestock farming, food production, and preservation led to widespread availability and increased global meat consumption.

The evolutionary dependence on meat consumption is reflected in significant changes in human anatomy, digestion, and metabolism. Fossil and physiological data indicate that hominins adapted to a diet rich in animal-derived nutrients, which played a crucial role in their development. The arid and seasonal environments in which early hominins evolved likely did not provide sufficient plant-based protein sources, unlike the wetland forests where their primate ancestors thrived. In contrast, grazing animals were abundant, offering a high-calorie, nutrient-dense food source, particularly in the form of easily digestible proteins and fats. One of the most profound biological consequences of meat consumption was the dramatic increase in brain size. Over the last 2 to 3 million years, the human brain has tripled in size, with the greatest level of encephalization observed in Homo erectus. Since the time of Australopithecus afarensis (approximately 4 million years ago), this expansion has been directly linked to access to energy-dense foods like meat. The human brain is composed largely of phosphoglycerides and cholesterol, which are rich in long-chain fatty acids, particularly arachidonic acid (ARA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). These essential fatty acids, primarily obtained from animal tissues, played a critical role in brain growth, cognitive function, and neural development. As brain size increased, digestive tract size decreased, reflecting the energy trade-off hypothesis (a shift towards a diet of higher-quality foods enabled a reduction in gut size). Compared to herbivorous primates, humans developed a relatively simple stomach, a smaller colon, but a proportionally longer small intestine, optimized for the absorption of nutrient-dense foods. Simultaneously, tooth size decreased, as cooked meat and other processed foods required less mechanical breakdown. A striking comparison highlights this shift. While chimpanzees spend an average of five hours a day chewing, modern hunter-gatherers who cook over fire spend only one hour on chewing, demonstrating the efficiency of cooking and meat consumption. Beyond biological adaptations, meat consumption shaped human social behavior. Hunting required cooperation, which fostered complex communication, pantomiming, and vocalization, a pivotal moment in the development of language. The practice of hunting and meat sharing also laid the foundation for social bonding and the formation of early human societies, marking one of the first steps in sociogenesis. Additionally, hunting rituals and the depiction of animals in prehistoric art suggest that early artistic expression was closely tied to the role of animals as prey. Throughout history, hunting and animal sacrifice rituals have been deeply embedded in various religious traditions, emphasizing the spiritual and symbolic importance of meat consumption in human culture.

Archaeological and paleontological evidence suggests that hominins began increasing their meat consumption around 3 million years ago. This shift was accompanied by the development of stone tools between 2.5 and 2.1 million years ago, enabling early humans to process and consume meat more efficiently. As a result, both brain and body size evolved, reinforcing the role of meat in fueling human development. The Australopithecus lineage marked a turning point in early hominin evolution. As the wetlands of East Africa shrank, these hominins ventured into expanding grasslands, a transition that necessitated dietary adaptations and triggered physiological and metabolic changes. One of the most significant adaptations was bipedalism, which is often considered one of the first evolutionary strategies related to human nutrition. Early evidence of postural bipedalism has been found in Australopithecus afarensis, but true locomotor bipedalism, which allowed for more efficient movement, did not fully emerge until Homo ergaster appeared between 1.9 and 1.5 million years ago. This more advanced form of bipedalism provided crucial advantages in hunting and load carrying, making food acquisition more effective. Around 2.4 million years ago, Homo habilis primarily obtained meat through scavenging, relying on carcasses left behind by predators. However, with the emergence of Homo erectus, hunting became a more dominant strategy. This shift in food acquisition coincided with a sharp increase in brain volume, body size, and life expectancy, while sexual dimorphism decreased, suggesting a shift toward greater social cooperation and shared food resources.

Another key milestone in human evolution was the control of fire and the advent of cooking. The ability to cook food improved digestion, increased nutrient absorption, and helped eliminate potential toxins, giving early humans a significant survival advantage. As hominins transitioned toward a more meat-inclusive diet, dental and digestive adaptations followed. The total surface area of chewing teeth initially increased, allowing for more efficient food processing. However, as cooking and tool use reduced the need for extensive chewing, posterior dentition decreased, leading to smaller postcanine teeth, reduced chewing muscles, and a weaker maximum bite force. At the same time, the intestines became smaller, reflecting a shift toward higher-quality, nutrient-dense foods that required less fermentation and digestion. Despite these adaptations, humans have always remained omnivores. Throughout evolution and history, the proportion of animal protein versus plant-based foods varied, allowing humans to thrive in diverse environments without reliance on a single food source. This dietary flexibility became a key factor in human survival and expansion, enabling populations to adapt to different ecological conditions across the globe.

Changes in diet have profoundly influenced the evolution of many species, shaping their anatomy, metabolism, and even behavior. Just as early humans adapted to a meat-rich diet, an example of an opposite evolutionary trajectory can be seen in the domestication of dogs. While wolves are strict carnivores, domesticated dogs evolved into omnivores after their transition from a hunter-scavenger lifestyle to living alongside agricultural societies. Compared to wolves, dogs developed a longer gastrointestinal tract, enabling them to digest plant-based foods more efficiently. One of the most significant genetic adaptations in dogs was the evolution of the AMY2B gene, which encodes for pancreatic alpha-amylase, an enzyme crucial for starch digestion. As dogs consumed more human food scraps, including grain-based waste products, they adapted to break down starch into maltose using the enzyme maltase-glucoamylase (MGAM), which is then converted into glucose and absorbed via the sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1). Additionally, the shift from a meat-based diet led to metabolic adjustments in fat synthesis and essential nutrient production. Since domesticated dogs received less meat, they adapted to synthesize key nutrients such as niacin, taurine, and arginine, which their wild ancestors primarily obtained from prey. However, dietary needs still vary across breeds, with some retaining a stronger reliance on animal-based nutrients than others.

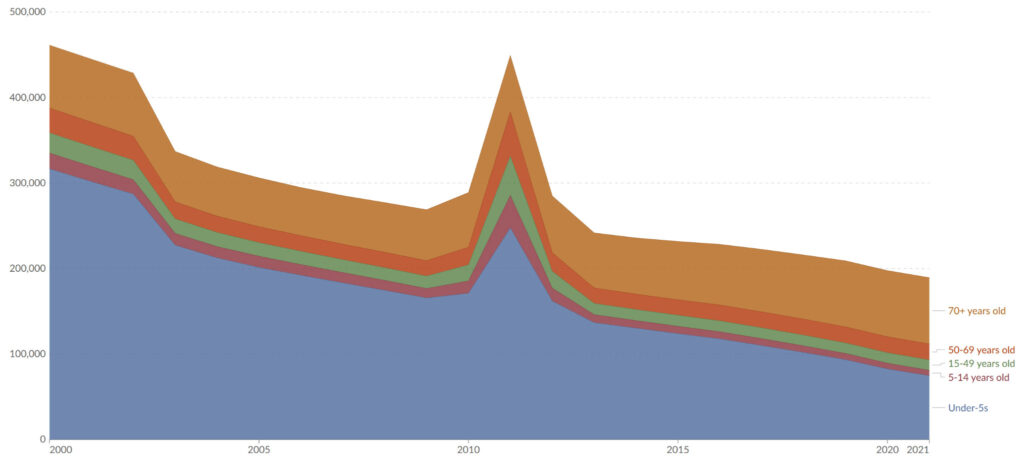

Human meat consumption has continued to evolve even in recent history. Between the mid-1950s and 1978, global meat consumption per capita increased from 60.8 kg per year to 98.0 kg per year, reflecting a nearly 50% rise. This increase was driven by advances in livestock farming, food production, and economic growth, making meat more accessible to a larger portion of the global population. In recent decades, evolving consumer preferences, shaped by growing interest in sustainability, animal welfare, and personal health, have contributed to a trend toward more diverse diets, including in some cases a reduction in meat intake. Despite these changes, animal protein remains an essential nutrient source, and its absence can have serious consequences particularly in vulnerable populations. Millions of people, particularly children in developing countries, suffer from malnutrition and starvation due to a deficiency of high-quality animal proteins (see Figure 2.), highlighting the need for nutritional balance rather than absolute dietary restrictions.

Figure 2. Deaths from protein-energy malnutrition by age group worldwide. Sourced from IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024) – with minor processing by Our World in Data.

This does not mean that a diet should consist only of meat. A balanced diet is crucial for optimal health, and plant-based foods provide essential nutrients that meat lacks. One of the most important plant-derived components missing from meat is dietary fiber, which plays a significant role in digestive health and disease prevention. Fiber is a complex mixture of nonstarch polysaccharides, including cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, which resist digestion by enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract. It is broadly classified into soluble and insoluble fiber, each with distinct physiological functions. Soluble fiber acts as a prebiotic, supporting gut health and playing a role in cholesterol reduction, glucose metabolism, and blood sugar regulation. By decreasing glucose absorption in the small intestine, it may help prevent and manage diabetes. Insoluble fiber contributes to intestinal regulation by increasing fecal bulk, absorbing water, and promoting regular bowel movements. It plays a key role in preventing constipation, obesity, and certain gastrointestinal disorders. Both types of fiber are associated with a lower risk of chronic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and some cancers, highlighting the necessity of a diet that combines both animal and plant-based foods.

In conclusion, while meat has been a fundamental part of human evolution and nutrition, it should be consumed as part of a diverse and balanced diet. The key lies not in eliminating meat or plant-based foods but in ensuring that all essential nutrients are adequately provided, supporting both human health and sustainability.

Resources:

Baig, M. A.; Ajayi, F. F.; Hamdi, M.; Baba, W.; Brishti, F. H.; Khalid, N.; Zhou, W.; Maqsood, S. Recent Research Advances in Meat Analogues: A Comprehensive Review on Production, Protein Sources, Quality Attributes, Analytical Techniques Used, and Consumer Perception. Food Reviews International, 2025, 41, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2024.2396855

Baltic, M. Z.; Boskovic, M. When man met meat: meat in human nutrition from ancient times till today. Procedia Food Science, 2015, 5, 6-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profoo.2015.09.002

Bosch, G.; Hagen-Plantinga, E. A.; Hendriks, W. H. Dietary nutrient profiles of wild wolves: insights for optimal dog nutrition? British Journal of Nutrition, 2015, 113, S40-S54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514002311

Debelo, H.; Novotny, J. A.; Ferruzzi, M. G. Vitamin A. Advances in Nutrition, 2017, 8, 6, 992-994. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.014720

Deschamps, Ch.; Humbert, D.; Zentek, J.; Denis, S.; Priymenko, N.; Apper, E.; Blanquet-Diot, S. From Chihuahua to Saint-Bernard: how did digestion and microbiota evolve with dog sizes. International Journal of Biological Science, 2022, 18, 13, 5086-5102. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.72770

Duraisamy, R.; Ganapathy, D. M.; Rajeshkumar, S. Vitamin K2 – A Review. International Journal of Dentistry and Oral Science, 2021, 8, 9, 4388-4392.

Gorbunova, N. A. Assessing the role of meat consumption in human evolutionary changes. A review. Theory and practice of meat processing, 2024, 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.21323/2414-438X-2024-9-1-53-64

IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024) – with minor processing by Our World in Data. “70+ years old” [dataset]. IHME, Global Burden of Disease, “Global Burden of Disease – Deaths and DALYs” [original data]. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/malnutrition-deaths-by-age (accessed on 19 March 2025)

Leroy, F.; Smith, N. W.; Adesogan, A. T.; Beal, T.; Iannotti, L.; Moughan, P. J.; Mann, N. The role of meat in the human diet: evolutionary aspects and nutritional value. Animal Frontiers, 2023, 13, 2, 11-18. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfac093

Mann, N. J. A brief history of meat in the human diet and current health implications. Meat Science, 2017, 144, 169-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.06.008

Maphosa, Y.; Jideani, V. A. Dietary Fiber Extraction for Human Nutrition – A Review. Food Reviews International, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2015.1057840

OpenStax. Digestive Systems. Biology, Open Text BC, https://opentextbc.ca/biology/chapter/15-1-digestive-systems/ (accessed on 17 March 2025)

Pereira, P. M. C. C.; Vicente, A. F. R. B. Meat nutritional composition and nutritive role in the human diet. Meat Science, 2013, 93, 586-592. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.09.018

Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E.; Atanasov, A. G.; Horbańczuk, J.; Wierzbicka, A. Bioactive Compounds in Functional Meat Products. Molecules, 2018, 23, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23020307

Ptáčníková, A. Evolutionary aspects of dog domestication and hybridization with wolf. Charles University in Prague, 2016, bachelor thesis.

Zmijewski, M. A. Vitamin D and Human Health. International Journal of Molecular Science, 2019, 20, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20010145