The liver is the principal organ responsible for cholesterol biosynthesis and regulation. The liver continuously monitors cholesterol concentrations within its own cells and throughout the body. In response, it activates or suppresses genes that control the expression of key proteins involved in cholesterol homeostasis. These include enzymes responsible for cholesterol synthesis, the number of hepatic receptors that mediate cholesterol uptake, and the rate of excretion either as free cholesterol or in the form of bile acids. This complex feedback system allows the liver to maintain cholesterol balance, but it also complicates our understanding of how dietary cholesterol impacts circulating levels.

Although nearly all cells in the human body have the capacity to synthesize cholesterol, approximately 50% of the total endogenous production occurs in the liver. As such, the liver plays a dominant role in determining the concentration of cholesterol circulating in the bloodstream. Cholesterol originating from both dietary sources (exogenous) and internal synthesis (endogenous) is packaged by the liver into very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), which are then secreted into the bloodstream. As VLDLs travel through the circulatory system, they are progressively metabolized by lipoprotein lipases, eventually giving rise to low-density lipoproteins (LDL). LDL particles can be taken up by peripheral tissues via LDL receptors to fulfill local cholesterol demands. When cellular cholesterol requirements are met, the excess cholesterol is transferred to high-density lipoproteins (HDL), which serve as the body’s primary mechanism for reverse cholesterol transport. HDL particles collect excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues and return it to the liver and intestines, where it is either recycled or excreted via the biliary system. This is why, in clinical medicine, LDL is referred to as “bad cholesterol,” while HDL is known as “good cholesterol.” Elevated LDL cholesterol levels are considered a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease, while higher HDL cholesterol levels are generally associated with a reduced risk.

What makes cholesterol so functionally versatile is its unique three-part structure, combining hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and rigid domains. This enables it to serve diverse biological roles. In mammalian cells, cholesterol is a fundamental component of the plasma membrane. One of its key roles is to provide structural integrity and rigidity, which compensates for the lack of a cell wall, as found in bacteria and plant cells. By inserting between phospholipids, cholesterol reduces membrane permeability to ions and small molecules such as gases. The concentration of cholesterol in cellular membranes varies according to function, with internal organelle membranes generally containing less cholesterol than the outer plasma membrane. This distribution is closely linked to the specific biophysical and functional requirements of each membrane type. Cholesterol can also play a role in cellular membranes as a component of signaling pathways.

If cholesterol had no other functions except to stabilize cellular membranes, it would still be an essential molecule. However, its importance extends further as a precursor for the synthesis of crucial hormones. Cholesterol serves as the precursor for hormones secreted by the adrenal gland, including cortisol and aldosterone, as well as the sex hormones as estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. These hormones regulate numerous physiological processes, from metabolism and stress response to reproductive function and fluid balance. Cholesterol serves also as a precursor for steroid hormones necessary for fetal development, including placental estrogens. Approximately half of the cholesterol required during fetal development is derived from LDL particles, while the other half is synthesized by the fetus itself. This dual-source system ensures adequate supply during critical stages of growth and organ formation.

Cholesterol is also the major structural component used in the synthesis of vitamin D and its metabolites, which are essential for bone health. Additionally, it plays a role in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and in the transport of these vitamins, particularly vitamins K and E, which rely on cholesterol in the form of LDL and HDL particles for distribution throughout the body. Oral forms of vitamin D also depend on this transport system.

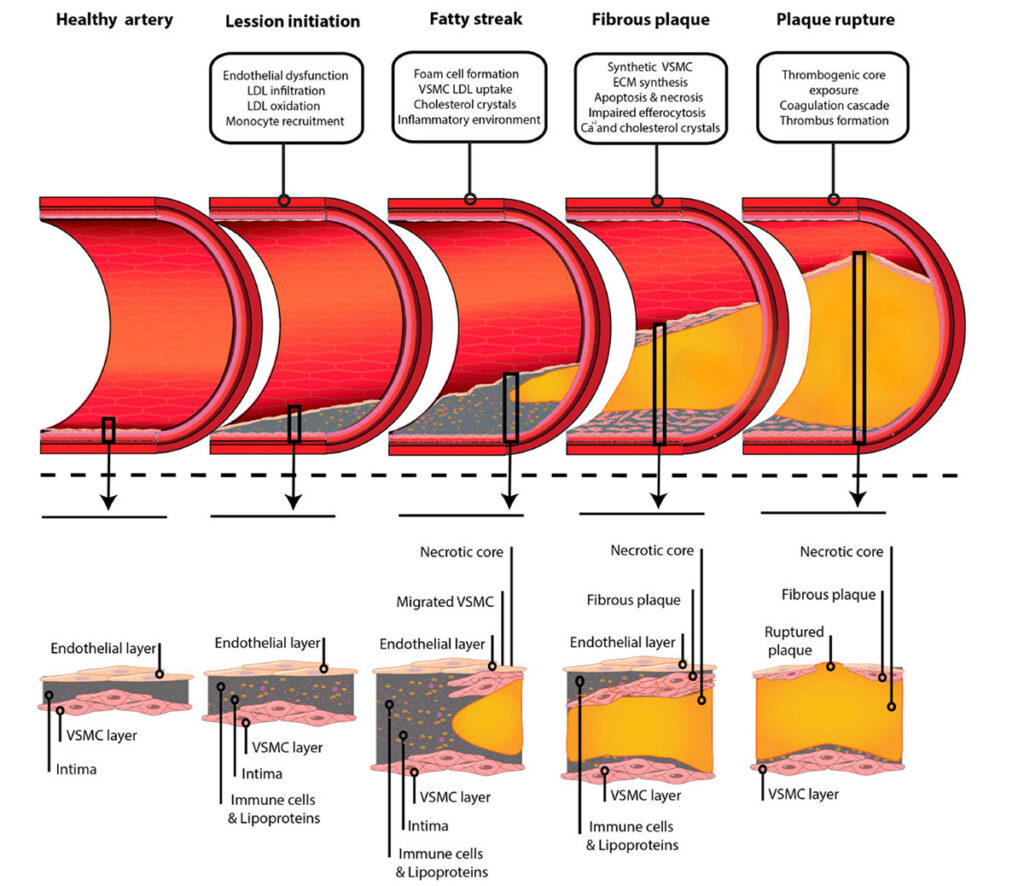

While cholesterol plays essential roles in our bodies, its excess, whether due to lifestyle or genetic predisposition, can lead to serious health issues. The most well-known of these is atherosclerosis, a disease in which cholesterol-rich particles accumulate within artery walls and silently progress until a major cardiovascular event occurs (see Figure 1.). Humans have a limited ability to catabolize cholesterol. When levels of circulating cholesterol-rich lipoproteins, particularly LDL, exceed the liver’s capacity to clear them, these particles begin to penetrate arterial walls, becoming embedded in the tissue. Once inside the arterial wall, LDL particles can undergo oxidation, triggering an inflammatory response. This initiates the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, composed of lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells), cellular debris, and cholesterol. These plaques are largely asymptomatic for years, and often only visible through CT scans or imaging tests. But when the build-up grows severe enough to reduce blood flow to vital organs, it can cause damage ranging from chronic ischemia to sudden infarction. The body doesn’t ignore this build-up. In response, macrophages, T cells, and other immune cells infiltrate the affected artery, releasing inflammatory cytokines. Over time, this immune activity can destabilize the plaque. The most dangerous scenario is plaque rupture: when the fibrous cap covering a plaque splits open, the inner contents spill into the bloodstream, triggering the formation of a blood clot (thrombus). This clot can immediately block the artery, causing a heart attack or stroke. Some forms of cholesterol, particularly free cholesterol and oxidized cholesterol (oxysterols), are toxic to vascular cells. These compounds kill lesional macrophages, promoting necrotic core formation within the plaque. This necrosis resembles an inflammatory abscess and can severely compromise arterial integrity, leading to acute vascular occlusion and infarction. While genetics play a role, atherosclerosis can be slowed or even halted by addressing its major risk factors. Proven preventive steps include stopping smoking, adopting a healthy diet low in saturated fats, staying physically active, and managing cholesterol levels through lifestyle or medication. Chronically elevated body cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia) doesn’t only threaten the heart and brain. It can also lead to cholesterol gallstones, liver dysfunction, cholesterol crystal metabolism, dermatological changes such as xanthelasma or other lipid deposits.

Figure 1. Schema of the development of atherosclerosis from a healthy artery to plaque rupture. Sourced from Jebari-Benslaiman et al. 2022.

Remarkably, atherosclerosis is not just a modern disease. Evidence of arterial plaque has been found in mummies from ancient Egypt, Peru, and the Americas, as well as in Ötzi the Tyrolean Iceman, who lived more than 5,000 years ago and was found preserved in ice in the Alps. Despite his active hunter-gatherer lifestyle, CT scans revealed calcifications in several major arteries, strongly suggesting atherosclerosis. However, in earlier times, shorter lifespans likely meant many individuals died before symptoms of cardiovascular disease could manifest. From a historical perspective, atherosclerosis has existed for thousands of years, yet the peak of coronary heart disease mortality was seen only in the 1960s, followed by a rapid decline, particularly in high-income countries. This drop is largely attributed to medical advances, improved diagnostics, and greater public awareness of healthy lifestyles.

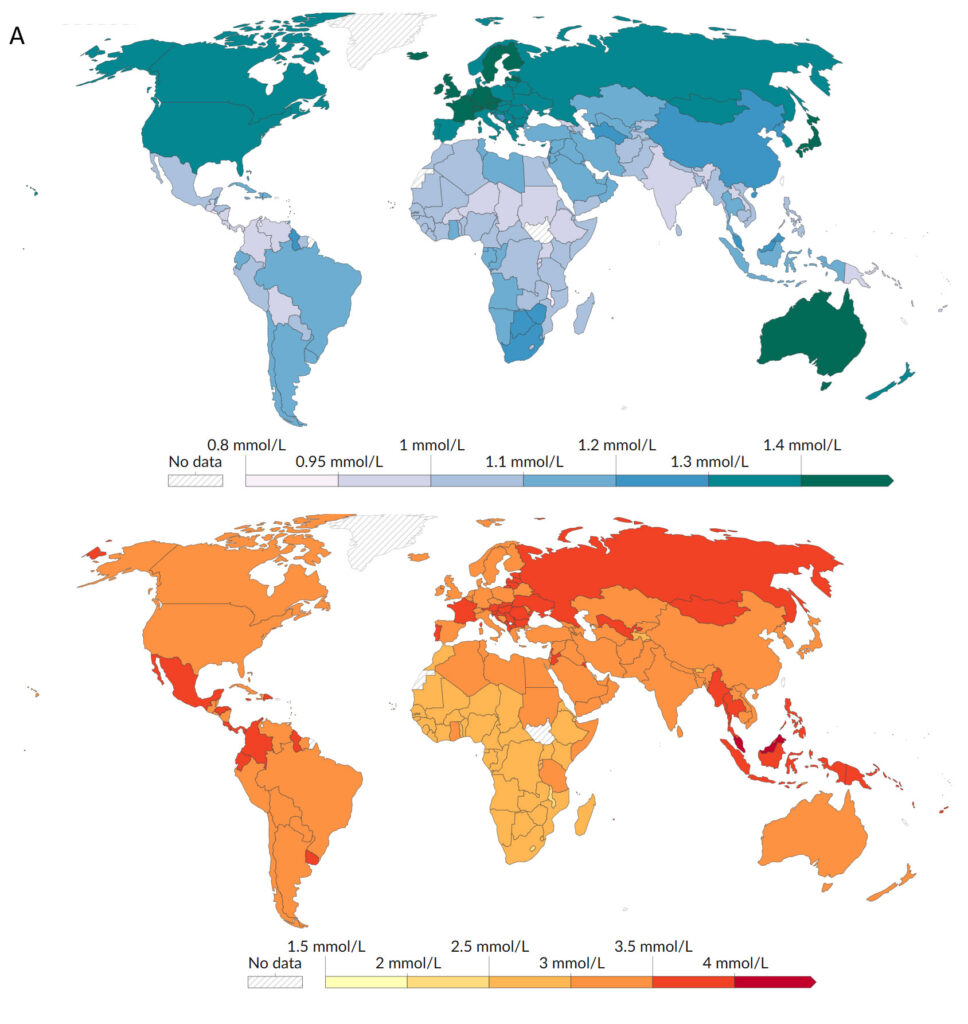

Figure 2. Average of HDL (A) and non-HDL (B) cholesterol levels, 2018. Sourced from World Health Organization – Global Health Observatory (2024) – processed by Our World in Data.

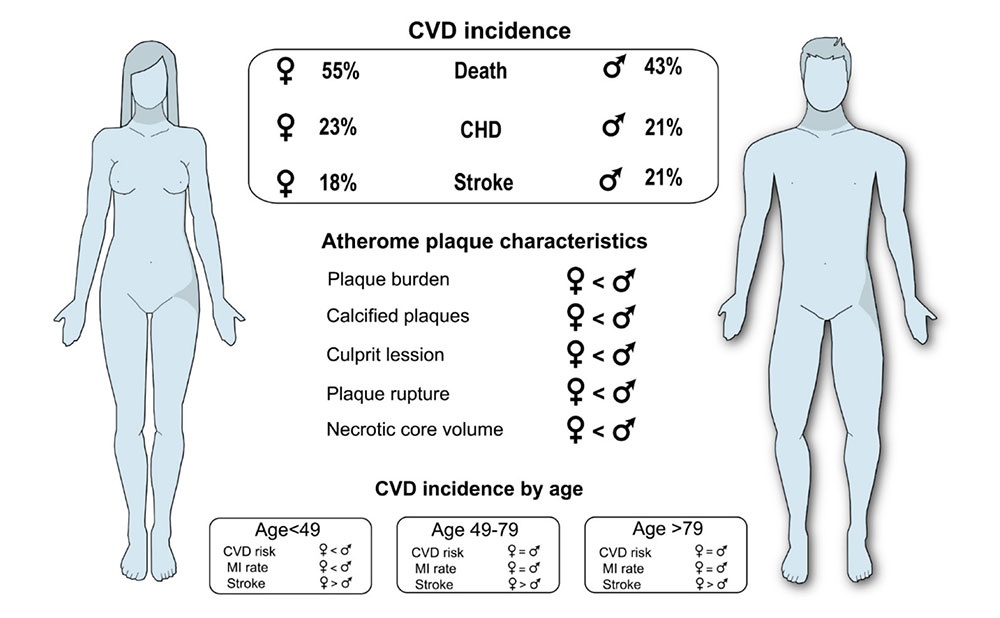

Population-wide disparities in HDL and non-HDL levels are significant and are shaped by geography, diet, lifestyle, and genetics. A global overview of average cholesterol levels by region (see Figure 2.) highlights the substantial variation between populations, emphasizing the role of both systemic factors and public health strategies in shaping cardiovascular risk. Ethnic and racial differences are evident: e.g., Black, Hispanic, and Asian-Pacific Islander males have higher stroke mortality rates (age-adjusted) than White males, suggesting social and biological influences at play. Furthermore, individual variability can also be found. Cholesterol absorption in the gut (often influenced by genetic factors) can significantly modulate the body’s overall cholesterol status, making dietary effects highly person-specific. For example, young women tend to be less vulnerable to atherosclerosis than men (see also Figure 3.), possibly due to hormonal protection and lower prevalence of smoking or hypertension.

Figure 3. Differential risk of cardiovascular disease by sex. Sourced from Jebari-Benslaiman et al. 2022.

Cultivated meat: a healthier way to enjoy animal protein? As our understanding of cholesterol and fatty acids evolves, so does our ability to shape the nutritional properties of the foods we eat. Cultivated meat, produced from animal cells without the need for traditional farming, represents a new frontier not only in food ethics and sustainability, but also in health. In theory, the lipid profile of cultivated meat could be adjusted through cultivation medium composition and metabolic engineering, allowing for the reduction of saturated fatty acids or cholesterol and the enrichment of beneficial omega-3 fatty acids. This offers the potential to create animal-based products that retain their biological value while minimizing some of the health risks associated with conventional meat.

Cholesterol remains a molecule of profound biological importance, essential for life, yet associated with the leading cause of death in the industrialized world. Its role in cardiovascular health is nuanced, shaped by diet, genetics, lifestyle, and medical interventions. The amount of cholesterol and saturated fat (which affects LDL levels) in one’s diet are well-established contributors to circulating LDL cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular mortality. However, the quantitative effect of dietary cholesterol can be difficult to interpret, owing to individual variability and numerous modifying factors that influence outcomes. Interestingly, those who consume little cholesterol regularly may experience greater increases in LDL when intake rises, while habitual high consumers often show minimal change. Clinical data supports that the efficacy of ezetimibe, a drug that blocks intestinal cholesterol absorption, in lowering LDL by ~20%, highlights the importance of dietary cholesterol as part of the broader cholesterol pool. However, cholesterol-rich foods often also contain saturated fatty acids (SFA), making it hard to isolate their individual effects. In this context, eggs, which are high in cholesterol but low in SFA, have been rigorously studied. Results consistently show no significant impact on CVD risk, suggesting that cholesterol alone is not the villain it was once believed to be. Despite our progress, atherosclerosis remains a dangerous and currently incurable condition. Yet intriguingly, LDL particles (long seen as harmful) may hold promise in a new role. Due to the overexpression of LDL receptors on rapidly dividing cancer cells, LDL-mediated transport may become a novel vehicle for anticancer drugs, allowing for targeted delivery. As cancer cells require abundant cholesterol for membrane synthesis, they could, paradoxically, become the very targets of the molecules once blamed for chronic disease. Ongoing research may turn yesterday’s cardiovascular threat into tomorrow’s therapeutic tool.

Resources:

Jebari-Benslaiman, S.; Galicia-García, U.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Olaetxea, J. R.; Allonza, I.; Vanderbroeck, K.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022, 23, 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23063346

Kenneth, R.; Feingold, M. D. The Effect of Diet on Cardiovascular Disease and Lipid and Lipoprotein Levels. Endotext, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK570127/ (accessed on 31 March 2025)

Luo, J.; Yang, H.; Song, B.-L. Mechanisms and regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2020, 21, 225-245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0190-7

Pang, Z. Progress in Atherosclerosis and treatments. Theoretical and Natural Science, 2024, 71, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-8818/2024.LA18222

Ridker, P. M. LDL cholesterol: controversies and future therapeutic directions. Lancet, 2014, 384, 607-617. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61009-6

Shade, D. S.; Shey, L.; Eaton, R. P. CHOLESTEROL REVIEW: A METABOLICALLY IMPORTANT MOLECULE. Endocrine Practice, 2020, 26, 12, 1514-1523. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP-2020-0347

Széliová, D.; Ruckerbauer, D. E.; Galleguillos, S. N.; Petersen, L. B.; Natter, K.; Hanscho, M.; Troyer, C.; Causon, T.; Schoeny, H.; Christensen, H. B.; Lee, D.-Y.; Lewis, N. E.; Koellensperger, G.; Hann, S.; Nielsen, L. K.; Borth, N.; Zanghellini, J. What CHO is made of: Variations in the biomass composition of Chinese hamster ovary cell lines. Metabolic Engineering 2020, 61, 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2020.06.002

Tabas, I. Cholesterol in health and disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2002, 110, 5, 5, 583-590. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI16381

World Health Organization – Global Health Observatory (2024) – processed by Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/good-cholesterol-levels-age-standardized and https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/average-non-hdl-cholesterol-levels (accessed on 14 April 2025)

Wurst, C.; Maixner, F.; Paladin, A.; Mussauer, A.; Valverde, G.; Narula, J.; Thompson, R.; Zink, A. Genetic Predisposition of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Ancient Human Remains. Annals of Global Health, 2024, 90, 1, 6, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4366