The digestion and absorption of nutrients are fundamental processes necessary for the survival of all living organisms. Over millions of years, these functions have evolved into the highly specialized and intricate tasks performed by the gastrointestinal system. The ability to break down food and extract its nutrients is essential for energy production, cellular function, and overall health. However, digestion is not a simple, uniform process. It is influenced by multiple factors, including food composition, nutrient bioavailability, and interactions between different dietary components. A varied diet is crucial for maintaining health, ensuring that the body receives all essential nutrients. However, even beneficial nutrients can become harmful when consumed in excessive amounts. Equally important is the bioavailability of nutrients, the extent to which they can be absorbed and utilized by the body. If a nutrient remains locked within a food matrix and cannot be accessed by digestive enzymes, it holds no nutritional value, regardless of its presence in the diet. Additionally, individual food components may interact in ways that either enhance or inhibit digestion. For example, certain plant-based compounds such as tannins (found in tea and some fruits), isothiocyanates (present in horseradish and wasabi), and reactive sulfur compounds can modify or crosslink protein side chains, reducing their availability for digestion. Conversely, some foods naturally contain hydrolytic enzymes that aid digestion by breaking down macromolecules into absorbable forms. The rate at which nutrients are released and absorbed also plays a key role in metabolism and health outcomes. For instance, the glycemic index measures how quickly carbohydrates are broken down and cause a rise in blood glucose levels, influencing energy regulation and insulin response. Despite the central role of digestion in human health, the gastrointestinal system remains one of the least studied and least understood processes in food science. As highlighted by researchers:

“All foods pass through a common unit operation, the gastrointestinal tract, yet it is the least studied and least understood of all food processes. To design the foods of the future, we need to understand what happens inside people in the same way as understanding any other process.”

Understanding digestion at both a biochemical and physiological level is essential for designing foods that optimize nutrient delivery and support long-term health.

The gastrointestinal tract is a sophisticated biological system responsible for converting food into absorbable and utilizable nutrients. It involves a complex series of versatile, multi-scale physicochemical processes that include the intake of food, its mechanical and chemical breakdown into basic molecular forms, nutrient absorption, transport to relevant organs, and elimination of waste. Structurally, it is composed of the digestive tract itself and several accessory organs, all regulated by a highly integrated neural network and hormonal control. The digestive tract is essentially a long, open-ended tube measuring approximately 8 to 9 meters in adults, extending from the mouth to the anus. It comprises the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Supporting digestion are the accessory organs: the teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, gall bladder, and pancreas, each playing a specific role in ensuring the efficient breakdown and absorption of nutrients.

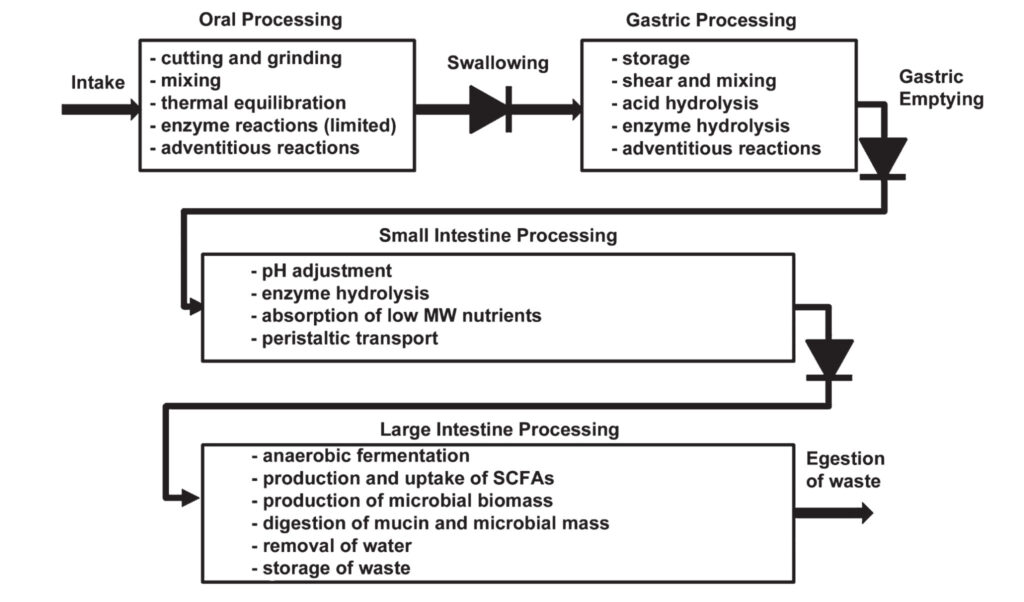

Digestion can be divided into four basic stages, each associated with different sections of the gastrointestinal tract (Figure 1). The process begins in the oral cavity, where mechanical and chemical digestion starts simultaneously. Chewing (mastication) breaks food down into smaller particles, increasing the surface area for enzymatic action. Human teeth are specialized for a range of tasks, incisors cut, canines tear, and molars grind and shear, ensuring efficient mechanical processing of diverse food types. As food is chewed, it is mixed with saliva, a fluid composed of 99% water along with electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, bicarbonate), mucin for lubrication, and enzymes. One of the key enzymes in saliva is salivary amylase, which initiates the breakdown of starch into maltose. Additionally, lysozyme, an antimicrobial enzyme, helps protect the oral cavity from bacterial infection. Once the food is formed into a cohesive bolus, it is swallowed and passes through the oesophagus via peristaltic movements into the stomach, where the next phase of digestion begins.

Once food enters the stomach, it encounters a highly acidic environment, which plays a crucial role in both digestion and pathogen defense. The stomach is anatomically divided into four main regions: the fundus, body, antrum, and pylorus. The fundus primarily serves as a temporary reservoir for ingested food and maintains a more neutral pH, allowing enzymes such as salivary amylase to continue acting on carbohydrates for a short period. As the food moves into the body and antrum, the environment becomes more acidic due to the secretion of hydrochloric acid (HCl) by specialized cells in the gastric wall. This acidic pH not only helps protect against pathogens but also activates digestive enzymes. The antrum and pylorus generate strong peristaltic waves, mechanically disrupting the food and mixing it thoroughly with gastric secretions. The stomach wall, which is 3–4 mm thick, consists of layers such as the gastric mucosa and muscularis, responsible for both chemical secretions and mechanical contractions. Two key enzymes secreted here are pepsin, which begins the digestion of proteins, and gastric lipase, which initiates the breakdown of fats. The release of these digestive substances is tightly regulated by the hormone gastrin, which stimulates the production of hydrogen ions, ultimately contributing to the formation of hydrochloric acid and maintaining the stomach’s low pH. This acidic environment is essential for protein denaturation, enzyme activation, and the initial phases of fat and protein digestion.

After gastric processing, the partially digested food, now called chyme, enters the small intestine, which is the longest and most critical part of the gastrointestinal tract, measuring approximately 6–7 meters in length. Despite its slender shape, its internal absorption surface is enormous (around 4,500 square meters) thanks to the presence of circular folds, villi, and microvilli, which greatly increase the mucosal area available for nutrient uptake. The small intestine is not only a major site of nutrient absorption, but also functions as a complex enzymatic bioreactor. It consists of three regions: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, each with specific roles in digestion and absorption. In the duodenum, the pH of the chyme is rapidly neutralized by bicarbonate secreted from the pancreas, creating optimal conditions for enzymatic activity. The pancreas also releases pancreatin, a complex mixture of hydrolytic enzymes. For example, trypsin and chymotrypsin continue the breakdown of proteins into smaller peptides. Pancreatic amylase converts remaining starches into disaccharides. Pancreatic lipase is responsible for digesting dietary fats. Additionally, bile acids from the gall bladder (containing bile salts, phospholipids, cholesterol, and bilirubin) emulsify fats into smaller droplets, significantly enhancing fat digestion by increasing the surface area for pancreatic lipase to act. As the chyme moves into the jejunum and ileum, absorption becomes the primary focus. These sections of the intestine provide an expansive surface area lined with specialized epithelial cells, which produce enzymes such as maltase-glucoamylase, sucrase-isomaltase, lactase, brush border peptidases, and additional lipases. These enzymes complete the breakdown of macromolecules into absorbable monomers like monosaccharides, amino acids, and fatty acids, which then pass through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream. However, digestion and absorption in the small intestine occur under constant competition with peristalsis, the rhythmic muscular contractions propelling the digesta forward. The rate of transit through the small intestine influences how much of the available nutrients are absorbed. If the process is too fast, unabsorbed nutrients may reach the colon, where they become substrates for colonic microbiota instead of entering systemic circulation. At the ileocecal junction, a specialized valve prevents backflow of colonic contents into the ileum and regulates the passage of digesta into the large intestine, ensuring one-way movement through the digestive tract.

After passing through the ileocecal valve, the remaining undigested material enters the large intestine, or colon, which measures approximately 150 cm in length. This final section of the gastrointestinal tract plays a crucial role in fermentation, water reabsorption, and electrolyte balance. The colon provides an anaerobic environment that is home to a dense and diverse community of microorganisms. In the adult human colon, there are estimated to be between 10¹¹ and 10¹³ bacterial cells, representing over a thousand different species. Collectively, these microbes possess a combined genome more than 100 times larger than the human genome. While the exact composition of the gut microbiota varies from person to person, most individuals share a core set of metabolic functions that are essential for host health. Within the colon, residual food components, particularly dietary fiber, undergo microbial fermentation. This process produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are absorbed by the host and used as an energy source. In some individuals, microbial fermentation may also lead to the production of gases like methane, depending on their microbial composition. As the digesta continues to move through the colon, the fermentation environment shifts from the breakdown of carbohydrates in the proximal colon to the fermentation of proteins and amino acids in the distal colon. This transition can influence the types of metabolites produced and may have implications for gut and overall health. Beyond fermentation, the colon is essential for recovering water and balancing electrolytes from the remaining material. Moreover, certain gut bacteria synthesize essential vitamins, such as vitamin B1 (thiamine), B3 (niacin), and vitamin K2, which can contribute to the host’s nutritional status.

Overall, transit time through the gastrointestinal tract varies depending on the individual and diet. On average, food remains in the stomach for 1–2 hours, in the small intestine for 3–4 hours, and may spend 24–48 hours in the colon, where extensive microbial activity continues long after digestion is complete.

Carbohydrates (Saccharides)

Following the general overview of the digestive system, we now turn to carbohydrates, which represent the main source of energy in the human diet and are key determinants of postprandial blood glucose levels. Understanding their digestion and absorption is fundamental to assessing how different foods influence metabolic health. Carbohydrates are typically classified by their chemical structure into: monosaccharides (e.g., glucose and fructose), oligosaccharides (e.g., lactose and sucrose), and polysaccharides (e.g., starch in plants and glycogen in animals). They can also be categorized as glycemic or non-glycemic, based on their ability to be digested and absorbed in the small intestine. Glycemic carbohydrates contribute to postprandial glycemia, as reflected by their glycemic index (GI), while non-glycemic carbohydrates, such as fiber, pass into the colon, where they may be fermented by gut microbiota.

The digestibility of carbohydrates can vary significantly, depending on several factors: viscosity and physical form of the food, cooking methods and processing techniques, the type of starch (amylose vs. amylopectin), the presence of antinutrients, content of fiber, fat and protein. For example, amylopectin-rich starches are generally digested more rapidly than those high in amylose, which can form complexes with lipids and resist enzymatic breakdown. Likewise, lipids may physically coat starch granules, further reducing enzymatic access and slowing digestion. The cooking process can also modify starch structure and increase or decrease digestibility, depending on the method used. Some plant-derived compounds naturally act as enzyme inhibitors, such as α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitors, which slow carbohydrate digestion and absorption. These compounds are of interest not only for their natural occurrence but also for their use in managing postprandial glucose levels, particularly in individuals with diabetes. Moreover, dietary fiber, especially viscous fiber, slows digestion and delays glucose absorption in the small intestine. Its beneficial effect is linked to both its viscosity and its ability to reduce starch accessibility to digestive enzymes.

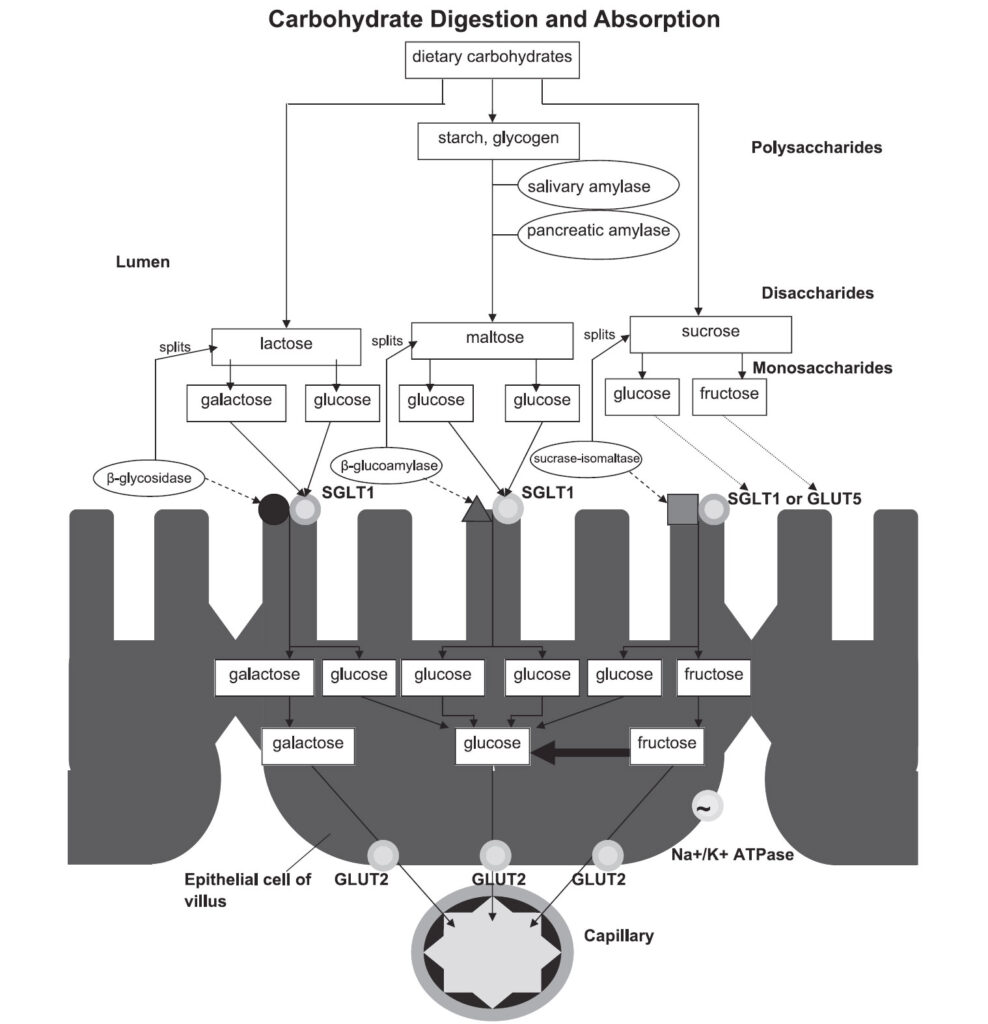

The digestion of complex carbohydrates begins in the mouth, where salivary amylase initiates the hydrolysis of starch into maltose and other oligosaccharides. However, salivary amylase is rapidly deactivated by gastric acid, unless shielded by the food matrix. In the small intestine, digestion resumes with pancreatic amylase, which continues breaking down starch into maltose, maltotriose, and isomaltose. These oligosaccharides are then processed by disaccharidases, a group of membrane-bound enzymes embedded in the enterocyte brush border, including: maltase-glucoamylase, sucrase-isomaltase, and lactase. These enzymes cleave disaccharides and oligosaccharides into absorbable monosaccharides, primarily glucose, fructose, and galactose. The spatial distribution of these enzymes across the small intestine is optimized to coordinate with the localization of glucose transporters, a phenomenon referred to as membrane digestion.

The resulting monosaccharides are then absorbed by enterocytes via specific transport proteins and rapidly transferred into the bloodstream, where they can be distributed throughout the body and utilized for energy or storage. A schematic overview of the digestion and absorption of dietary carbohydrates, along with key enzymes and transporters involved in these processes, is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Summary of the basic steps involved in carbohydrate digestion and absorption, highlighting important enzymes and transporters in the intestinal lumen and epithelial cells. Sourced from Goodman 2010.

Proteins

After carbohydrates, dietary proteins represent another fundamental nutrient that must be effectively broken down for proper absorption and utilization. On average, the human digestive system processes approximately 70–100 grams of dietary protein and 35–200 grams of endogenous proteins daily, including digestive enzymes and sloughed-off epithelial cells. The goal of protein digestion is to hydrolyze complex proteins into their basic building blocks, amino acids and small peptides, which can be absorbed across the intestinal lining. Protein digestion is more complex than that of carbohydrates or lipids due to the wide variety of peptide bonds and the specific action required by different enzymes.

In addition to the role of digestive enzymes and transport mechanisms, the structural characteristics of the protein itself significantly influence its digestibility. The extent to which proteins are structured, whether they are soluble, aggregated, or form clots, determines how accessible they are to proteases in the gastric and intestinal environments. Soluble proteins are generally more easily hydrolyzed, as digestive enzymes can readily access their peptide bonds. However, the acidic environment of the stomach can induce protein aggregation, leading to the formation of dense, porous clots when proteins come into contact with gastric juice. These clots are only marginally permeable to gastric secretions, which reduces the ability of enzymes like pepsin, the key protease active in the stomach, to penetrate and digest the protein core, ultimately lowering digestibility. In addition to physical accessibility, enzyme activity is also influenced by gastric pH. Pepsin functions optimally at a pH around 2. However, the ingestion of food increases gastric pH from a fasting pH of 1.3 – 2.5 to 4.5 – 5.8 postprandially temporarily reducing pepsin’s activity until the acid level is restored. The pH distribution in the stomach varies over time and depends on the type and composition of the meal consumed. Furthermore, protein digestibility, especially from plant-based sources, can be negatively affected by the presence of compounds traditionally referred to as antinutritional factors, such as phytates, tannins, or protease inhibitors. These substances can interfere with enzymatic activity, further reducing the efficiency of protein digestion and nutrient absorption.

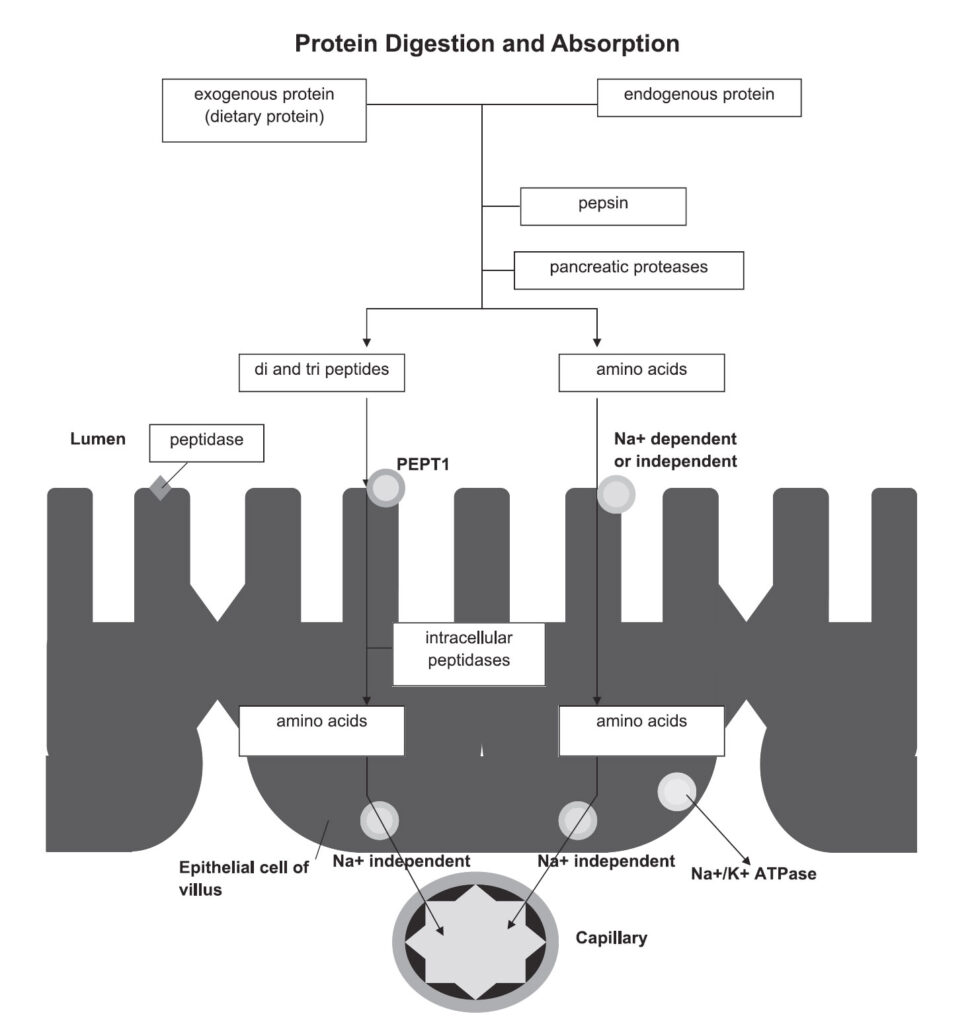

There are two main classes of proteolytic enzymes involved: endopeptidases and exopeptidases. Endopeptidases cleave internal peptide bonds within the protein structure, producing large polypeptides. Exopeptidases remove individual amino acids from the ends of the polypeptide chains. The process begins in the stomach, where the enzyme pepsin (endopeptidase) initiates protein breakdown. Pepsin is secreted in its inactive form, pepsinogen, by the gastric mucosa. Upon exposure to gastric hydrochloric acid, pepsinogen undergoes a conformational change and becomes activated. In addition to enzyme activation, the strongly acidic environment (pH 1.5–3.5) denatures proteins, unraveling their structures and making peptide bonds more accessible to enzymatic action.

Protein digestion continues in the small intestine, where a range of pancreatic proteases (including trypsin, chymotrypsin, elastase, and carboxypeptidases) further break down polypeptides into oligopeptides and free amino acids. Absorption of the resulting fragments occurs also in the small intestine. Specific transport proteins embedded in the membranes of enterocytes (intestinal absorptive cells) facilitate the uptake of free amino acids as well as dipeptides and tripeptides into the bloodstream. Once absorbed, amino acids can be used for tissue repair, enzyme production, neurotransmitter synthesis, and other vital metabolic functions. Figure 3 summarizes the main stages of protein digestion and absorption, including the roles of pepsin, pancreatic enzymes, and the transporters involved in moving amino acids and peptides from the intestinal lumen into the bloodstream.

Figure 3. Summary of the basic steps involved in protein digestion and absorption, highlighting important enzymes and transporters in the intestinal lumen and epithelial cells. Sourced from Goodman 2010.

Fats (Lipids)

Dietary lipids are primarily composed of long-chain fatty acids typically containing 16 to 20 carbon atoms. Medium-chain fatty acids (C8–C12) occur less frequently in natural foods (with some exceptions, such as coconut oil), while short-chain fatty acids (C2–C4) are not found in food but are instead produced as end products of microbial fermentation in the colon and absorbed there. The digestion of lipids is influenced not only by the composition and structure of lipids, but also by the physical form and food matrix, emulsification, type of fatty acids, digestive enzymes, presence of bile salts and calcium ions, and dietary fiber. Lipids in natural foods occur as droplets or globules stabilized by emulsifying layers, such as milk-fat globule membranes or oil bodies in seeds. The surface area of these droplets (especially after emulsification) plays a key role, as lipases act at the lipid–water interface.

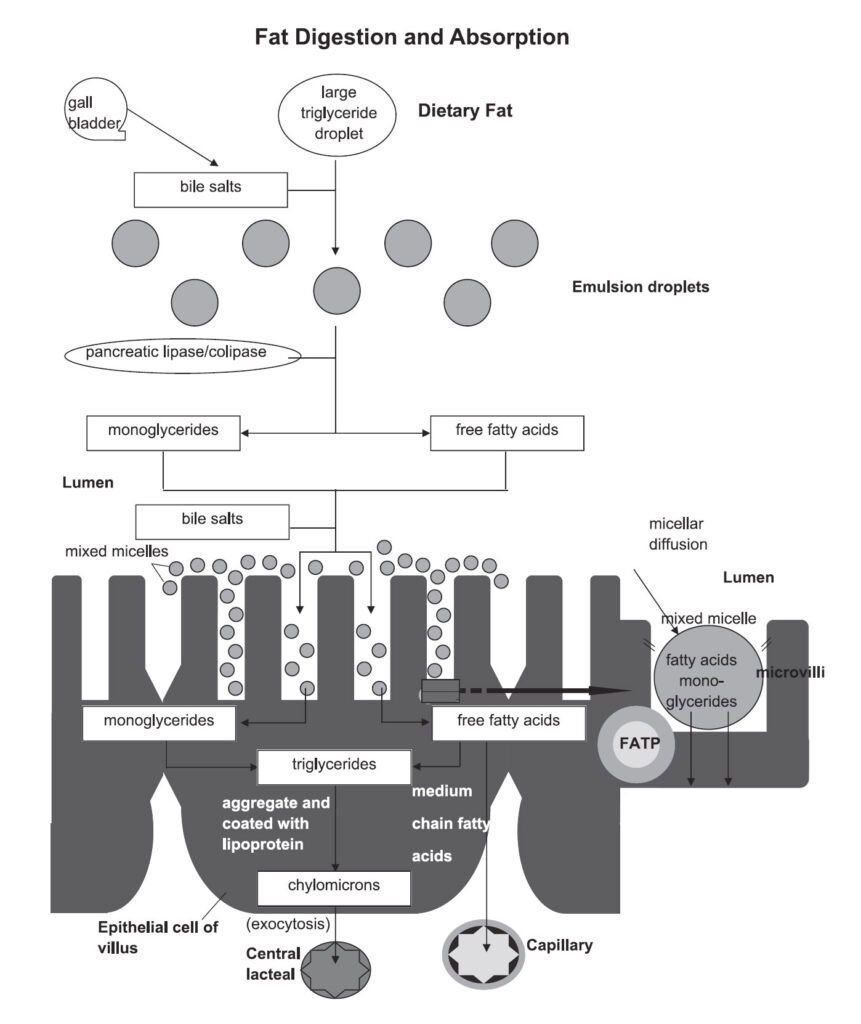

Fat digestion begins in the mouth, where lingual lipase secreted by glands on the tongue initiates the hydrolysis of triglycerides. This process continues in the stomach, where both lingual and gastric lipases act on dietary fats, although only about 15% of total lipid digestion occurs before chyme enters the small intestine. Once dietary fats reach the duodenum, their presence triggers the release of bile from the gallbladder and pancreatic enzymes from pancreas, which play a key role in the hydrolytic breakdown of lipids. Pancreatic lipase, activated by colipase (converted from procolipase by trypsin), catalyzes the breakdown of triglycerides into monoglycerides and free fatty acids. These digestion products, along with bile salts, form micelles, tiny transport structures that facilitate the uptake of lipids by enterocytes (intestinal absorptive cells). Once absorbed, lipid-soluble molecules (composed of bile salts and mixed lipids like fatty acids, monoglycerides, lysophospholipids, and cholesterol) bind to serum albumin and are transported through the lymphatic or circulatory system to the liver for further processing.

In the colon, short-chain fatty acids are produced by bacterial fermentation of undigested fats and fiber. These are absorbed locally and serve as an important energy source for colonocytes, highlighting the metabolic importance of microbial contributions to fat digestion. These complex steps of fat digestion and absorption are summarized in Figure 4. Lipid digestion is generally highly effective, with more than 95% of dietary fats being digested and absorbed following the consumption of a typical meal. An exception to the typically high efficiency of lipid digestion is found in oilseeds such as nuts and soybeans, where intact cell walls can hinder lipid release and absorption. Studies have shown that the metabolizable energy from almonds may be up to 30% lower than estimated by standard energy calculations, with similar discrepancies reported for other nuts like walnuts.

Figure 4. Summary of the basic steps involved in fat digestion and absorption, highlighting important factors and transporters in the intestinal lumen and epithelial cells. Sourced from Goodman 2010 with modifications.

Understanding the digestion and absorption of the three main macronutrient groups, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, reveals the complexity of our gastrointestinal system and its remarkable ability to extract nutrients from a wide variety of foods. While the fundamental principles of digestion apply to all humans, individual differences in enzymatic activity, microbiota composition, and genetic predispositions can lead to significant variation in nutrient utilization across populations. For instance, lactase deficiency, which impairs the ability to digest lactose in milk, is common among adults in many ethnic groups, such as populations in Asia, and pastoralist groups like the Maasai, Tutsi, and Fulani. Similarly, trehalase deficiency, which affects the breakdown of the disaccharide trehalose, is more prevalent among Inuit populations in Greenland. Differences can also be observed in fiber digestion, where the gut microbiota plays a central role. Gut microbiota diversity tends to be higher in populations from non-Western regions, especially parts of Africa, compared to those in more industrialized areas. Populations consuming high-fiber vegetarian diets have microbial adaptations that improve their ability to ferment and extract energy from plant-based polysaccharides.

These examples illustrate how diet and digestion co-evolve, and how the composition of food (including its structure, nutrient form, and digestibility) matters as much as its quantity. In this context, cultivated meat emerges as a novel dietary option with a familiar biological profile. Since it is made from real animal cells, it contains the same essential amino acids, proteins, and fats as conventional meat. This means it could be digested and absorbed in the same way, offering a complete and bioavailable source of nutrition. Moreover, cultivated meat production allows for precise control of composition, potentially enabling customerization (e.g., the modification of fat profiles), reduction of harmful compounds, or enrichment with specific nutrients (vitamins, taurine). This opens the door to designing meat that not only mirrors traditional products but may even offer improved health outcomes, especially for populations with specific dietary challenges.

Still, it’s important to emphasize that no single food can meet all of our nutritional needs. Regardless of the protein source, plant, animal, or cultivated, a diverse and balanced diet remains the cornerstone of good health. To function optimally, the human body requires not only proteins, but also fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber, each contributing in unique and complementary ways to metabolism, development, and disease prevention.

Resources:

Boland, M. Human digestion – a processing perspective. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2016, 96, 7, 2275-2283. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.7601

Capuano, E.; Janssen, A. E. M. Food Matrix and Macronutrient Digestion. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2021, 12, 193-212. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-032519-051646

Giacco, R.; Costabile, G.; Riccardi, G. Metabolic effects of dietary carbohydrates: The importance of food digestion. Food Research International, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2015.10.026

Norton, J. E.; Wallis, G. A.; Spyropoulos, F.; Lillford, P. J.; Norton, I. T. Designing food structures for nutrition and health benefits. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2014, 5, 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-030713-092315

Senghor, B.; Sokhna, Ch.; Ruimy, R.; Lagier, J.-Ch. Gut microbiota diversity according to dietary habits and geographical provenance. Human Microbiome Journal, 2018, 7-8, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humic.2018.01.001

Sensoy, I. A review on the food digestion in the digestive tract and the used in vitro models. Current Research in Food Science, 2021, 4, 308-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2021.04.004