Humans have been influencing the genetics of plants and animals for thousands of years. Just consider the differences between a Chihuahua and a Great Dane. Now, comparing both breeds to their wild ancestor, the wolf, the differences are striking. In traditional agriculture and animal breeding, individuals with desirable traits were selected and crossbred to create new variants through a process known as selective breeding. However, this method is time-consuming and requires multiple generations to achieve the desired results. Modern genetic engineering has accelerated this process by enabling the direct transfer or modification of specific genes within an organism. By introducing specific genes, it is possible to produce the same desired traits but in a much shorter time. This advancement gave rise to what we call genetically modified organisms and genetically modified food. While definitions may vary, genetically modified organisms are generally understood as organisms whose genetic material has been altered by methods other than natural breeding or recombination. This category includes animals, plants, and microorganisms.

The foundation of modern genetic modification began in 1972, when Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer developed the first methods to cut and reassemble DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) strands at specific locations. This breakthrough enabled scientists to insert DNA sequences directly into living cells, opening the door to entirely new possibilities in biotechnology. Since then, progress has been rapid, particularly in the last few decades. Genetic modification now allows the crossing of species barriers, creating new variants with properties previously unattainable through conventional methods. Despite these advancements, genetic modification remains a highly controversial topic today, sparking debates on ethics, safety, and the future of food production.

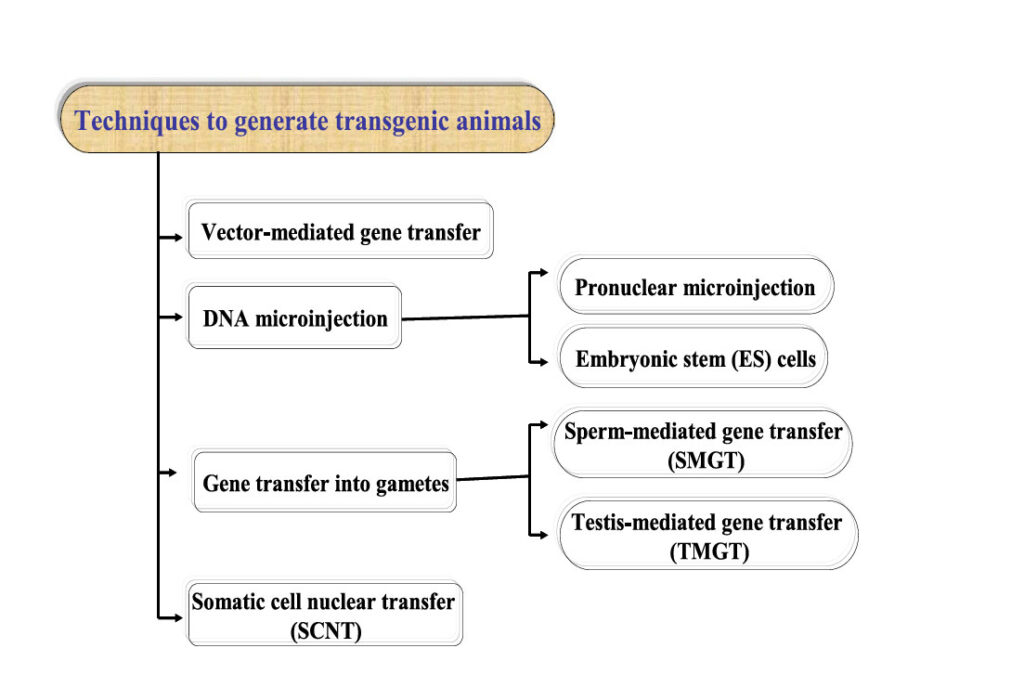

Genetic engineering focuses on the targeted modification of an organism’s traits by directly altering its DNA. Using recombinant DNA technology, scientists can transfer genes across species boundaries, introducing new characteristics into plants, bacteria, viruses, or animals that would otherwise be impossible through natural breeding. One of the earliest applications of this technology was the creation of transgenic organisms, where genes from unrelated species are introduced to achieve specific outcomes. The primary approaches used to create transgenic animals are illustrated in Figure 1. Historically, the first genetically modified organism was created in the 1970s when scientists introduced foreign genes into the bacterium Escherichia coli. By 1985, this technology extended to farm animals, opening new avenues for improving agriculture. Transgenic modifications in farm animals offer several advantages, including improved feed efficiency and growth rate, better carcass composition, enhanced milk production and composition, and increased resistance to diseases (e.g., resistance to BSE in cows). Beyond food production, genetic engineering is also applied in medicine and biotechnology. For instance, genetically modified animals can produce human-compatible organs for transplantation (xenotransplantation) or serve as models for studying diseases and testing new treatments. A particularly interesting innovation is BioSteel silk, a highly strong, flexible, and lightweight fiber with diverse applications, including medical materials, the textile industry, and ballistic equipment. This remarkable material was created by inserting spider genes into goats, enabling them to produce silk proteins in their milk.

Figure 1. The primary approaches used to create transgenic animals. Sourced from Shakweer et al. 2023.

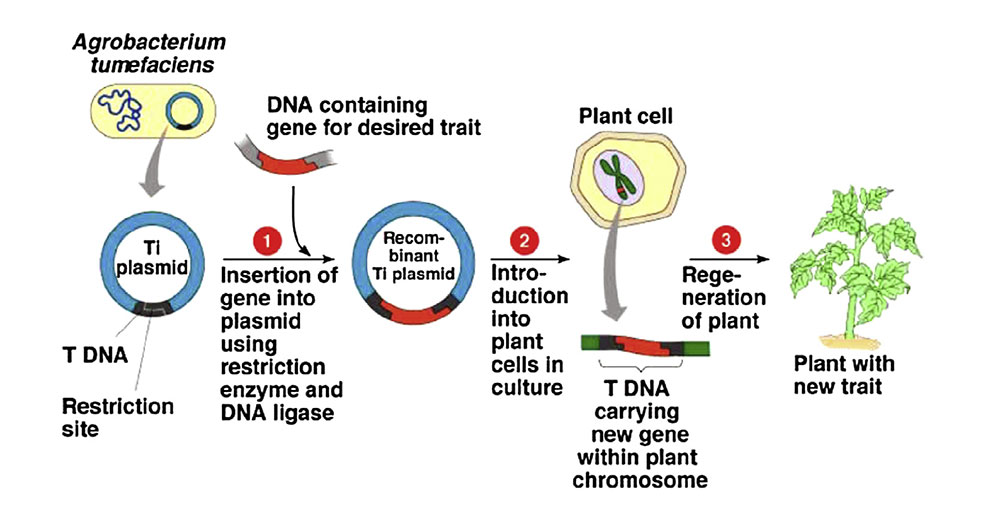

In 1983, the first genetically modified plant, a tobacco plant with antibiotic resistance, was developed. This was achieved using a new method introduced in the 1980s that utilized the pathogenic bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens to transfer genes into plants (Figure 2). Many agronomically important plant species, such as tobacco, corn, tomato, potato, banana, alfalfa, and canola, have since been used to express various recombinant proteins. Genetically engineered plants provide considerable advantages by increasing production yield, enhancing nutritional content, and creating resistance to insects, pests, viruses, and specific herbicides. Beyond agricultural use, genetically modified plants now play an important role in medicine, producing antibodies, therapeutic proteins, and vaccines.

Figure 2. Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated transfer. Sourced from Rani & Usha 2013.

The use of genetically modified organisms has led to significant concerns, including their potential impact on human health (e.g. antibiotic resistance, allergenicity, toxicity), their possible negative effects on the natural environment, and public discomfort with consuming DNA from other sources, such as viruses or bacteria. This has also sparked a debate about what is ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural,’ as well as the idea of ‘playing God’. And this is despite the fact that there is evidence suggesting that gene transfer between species is not as unnatural as we might think. For example, the marine slug Elysia chlorotica has integrated a gene from algae into its genome, granting it the ability to perform photosynthesis.

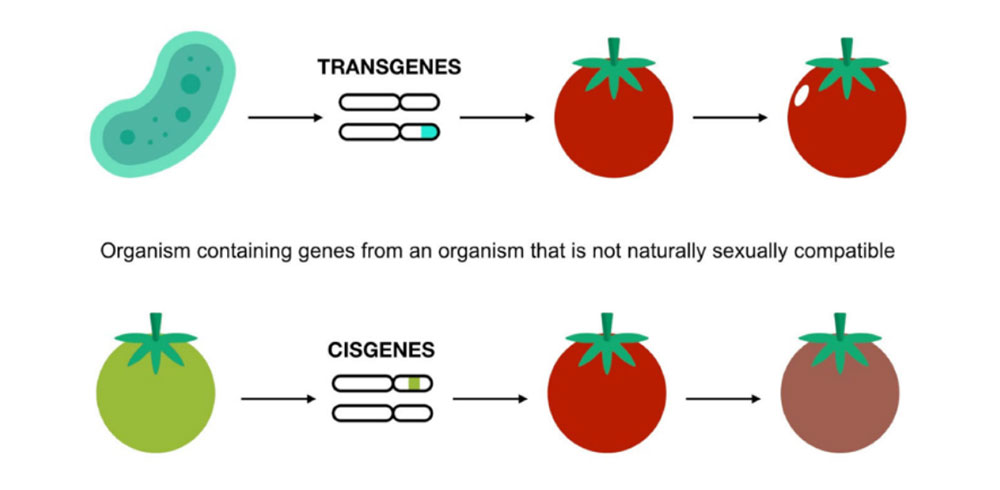

To address some of the ethical and safety concerns, researchers have developed cisgenic modification, a technique that introduces genes from the same species or a closely related one. Unlike transgenesis, where genes can be transferred between completely unrelated species, cisgenesis works with genetic material that could also be introduced through traditional breeding. (see Figure 3). Cisgenesis carries no more risks than traditional breeding, such as impacts on non-target organisms, soil ecosystems, toxicity, and allergenic risks in genetically modified food or feed. Cisgenic and conventionally bred organisms could be treated similarly by regulators from a safety perspective, as the release and marketing of cisgenic organisms is as safe as the release and marketing of traditionally bred ones. While in traditional breeding, it can take years to successfully select organisms with the desired trait, cisgenesis is highly efficient, allowing for precise genetic improvements in a much shorter time. The problem is that the selected gene is often linked to a number of other genes that are not desirable. During crossbreeding, these genes (and thus their associated traits) are passed on to future generations, requiring multiple backcrosses to eliminate them. This process can be extremely time-consuming.

Figure 3. Contrast between transgenic and cisgenic modification techniques. Sourced from Rodriguez et al. 2013.

Yet, critics continue to view these “new” technologies with suspicion, often branding genetically modified foods with alarmist labels like Frankenfood or Farmageddon. In reality, genetic engineering holds immense potential to address the needs of the ever-growing global population. Ironically, while the use of genetic modification in medicine is widely accepted, food biotechnology is scrutinized with extreme caution. Another paradox is that genetically modified food technology originated in Europe, yet EU countries remain the most resistant to its adoption. The legislative framework is strict. While some genetically modified food and feed products have been approved for sale in the EU, their cultivation is limited, and only a small number of genetically modified crops are allowed to be grown commercially. From a scientific perspective, this resistance seems illogical, especially when considering breeding methods such as mutagenesis via radiation, which is legally accepted despite being an uncontrolled process that can generate numerous (both desired and unintended) mutations. Compared to targeted genetic modifications, this method is arguably more controversial. Yet mutagenesis is responsible for thousands of commercial plant varieties. Furthermore, European regulations make no distinction between cisgenic and transgenic modifications. In 2006, a group of scientists proposed exempting cisgenic plants from the stringent safety assessments required for transgenic organisms. They argued that cisgenic transfer poses no greater risk than traditional breeding, where large segments of DNA are naturally exchanged. The proposal sparked significant debate, yet no meaningful legislative changes have followed. The scientific community continues to advocate for a more nuanced approach that acknowledges the differences between genetic modification techniques and applies regulations based on actual risk rather than outdated perceptions.

Despite all of humanity’s advancements, malnutrition remains a leading risk factor for health issues and mortality worldwide. The nutritional and health benefits of genetic engineering are significant and will play a crucial role in sustaining the growing global population, which, according to the United Nations, is expected to double by 2050. Therefore, genetic engineering is the logical way to feed and treat an overpopulated world. Genetic engineering tools, originally developed for cell and gene therapy industries, can be equally applied to cultivated meat, offering significant potential for optimizing cellular processes. Several proof-of-concept studies have already demonstrated key advancements, including the generation of immortalized cell lines, the removal of growth factor dependencies from serum-free proliferation media, and enhancements in nutritional value. Some products can be intentionally modified to enhance the levels of specific nutrients or to eliminate compounds with antinutritional effects. These modifications aim to reduce adverse reactions in certain individuals, for example, in people with alpha-gal syndrome (a meat allergy), removing alpha-gal sugars from the surface of cells can significantly reduce the risk of allergic responses. Additionally, the expression or upregulation of proteins and bioactive compounds not typically found in animal products, such as antioxidant carotenoids, may help improve the nutritional value and overall quality of the food. A growing number of industry patents now target cellular traits such as reprogramming, proliferation, and differentiation, reflecting the increasing interest in applying these technologies.

However, despite these advancements, the cultivated meat industry has largely favored spontaneous adaptation of cells over genetic engineering, opting for slower but regulatory-friendly approaches. Nonetheless, genetic engineering presents a unique opportunity to optimize, enhance, or eliminate specific cellular functions in a precise, reproducible, and combinatorial manner, enabling the acquisition of desired phenotypes for large-scale production. The regulatory landscape remains a crucial factor in determining the extent of genetic modifications that can be implemented, particularly regarding cisgenic vs. transgenic approaches. Importantly, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already approved a cultivated chicken product derived from cisgenically immortalized cells, setting a precedent for the use of such technologies in food production. Beyond optimizing cell growth and efficiency, genetic engineering also holds substantial promise in improving the nutritional profile of cultivated meat, including increasing vitamin and essential amino acid content, refining fatty acid composition, and reducing harmful compounds, all of which contribute to making cultivated meat a nutritious and healthy dietary option for consumers. While the debate over genetic modification continues, one thing is clear: innovation in this field will shape the future of food. The question is not whether we should use this technology but how we can ensure it benefits people, animals and the planet.

Resources:

Cai, J.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Dong, S.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, S. Industrialization progress and challenges of cultivated meat. Journal of Future Foods, 2024, 4-2, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfutfo.2023.06.002

Gama Sosa, M. A.; De Gasperi, R.; Elder, G. A. Animal transgenesis: an overview. Brain Structure and Function, 2010, 214, 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-009-0230-8

Karalis, D. T.; Karalis, T.; Karalis, S.; Kleisiari, A. S. Genetically Modified Products, Perspectives and Challenges. Cureus, 2020, 12, 3, e7306. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7306

Kronberger, N.; Wagner, W.; Nagata, M. How Natural Is “More Natural”? The Role of Method, Type of Transfer, and Familiarity for Public Perceptions of Cisgenic and Transgenic Modification. Science communication, 2014, 36, 1, 106-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547013500773

Ong, K. J.; Johnston, J.; Datar, I.; Sewalt, V.; Holmes, D.; Shatkin, J. A. Food safety considerations and research priorities for the cultured meat and seafood industry. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2021, 20, 5421-5448. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12853

Rani, S. J.; Usha, R. Transgenic plants: Types, benefits, public concerns and future. Journal of Pharmacy Research, 2013, 879-883

Riquelme-Guzmán, C.; Stout, A. J.; Kaplan, D.L.; Flack, J. E. Unlocking the potential of cultivated meat through cell line engineering. Iscience, 2024, 27, 10, 110877

Shakweer, W. M. E.; Krivoruchko, A. Y.; Dessouki, Sh. M.; Khattab, A. A. A review of transgenic animal techniques and their applications. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, 2023, 21, 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43141-023-00502-z

Schouten, H. J.; Krens, F. A.; Jacobsen, E. Cisgenic plants are similar to traditionally bred plants: international regulations for genetically modified organisms should be altered to exempt cisgenesis. EMBO Reports, 2006, 7, 8, 750-3. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400769

Uzogara, S. G. The impact of genetic modification of human foods in the 21st century: A review. Biotechnology Advances, 2000, 18, 179–206

Van Eenennaam, A. L. Genetic modification of food animals. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2017, 44, 27–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2016.10.007

Vasudevan, S. N.; Pooja, S. K.; Raju, T. J.; Damini, C. S. Cisgenics and intragenics: boon or bane for crop improvement. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2023, 14, 1275145. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpls.2023.1275145

Vega Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez-Oramas, C.; Sanjuán Velázquez, E.; Hardisson de la Torre, A.; Rubio Armendáriz, C.; Carrascosa Iruzubieta, C. Myths and Realities about Genetically Modified Food: A Risk-Benefit Analysis. Applied Science, 2022, 12, 2861. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12062861

Yali, W. Application of Genetically Modified Organism (GMO) crop technology and its implications in modern agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Technology, 2022, 8, 1, 014-020. https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/2455-815X.000139