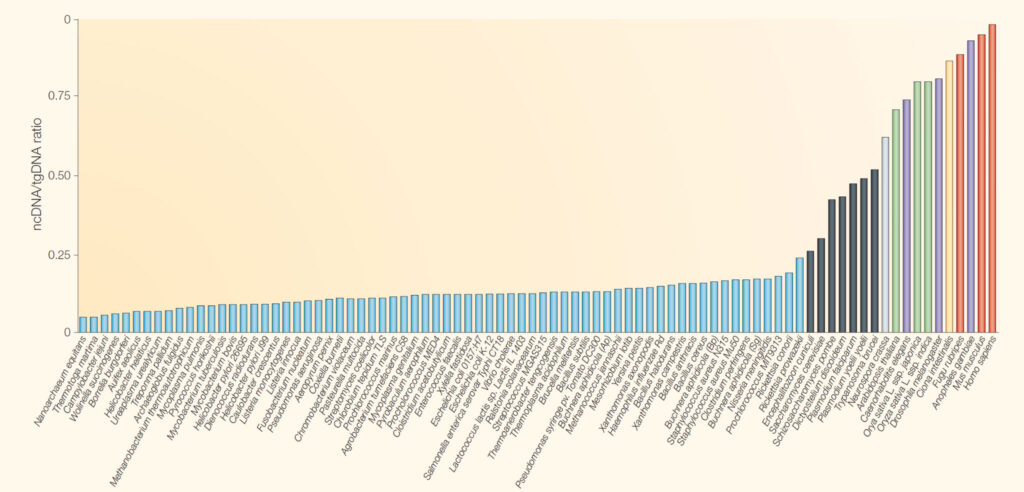

Figure 1. Proportion of non-coding DNA (ncDNA) relative to total genomic DNA (tgDNA) across different organisms, ranging from simple prokaryotes to humans. As organismal complexity increases, the proportion of non-coding DNA tends to rise, highlighting its potential role in regulatory and developmental processes rather than direct protein coding. Sourced from Mattick 2004.

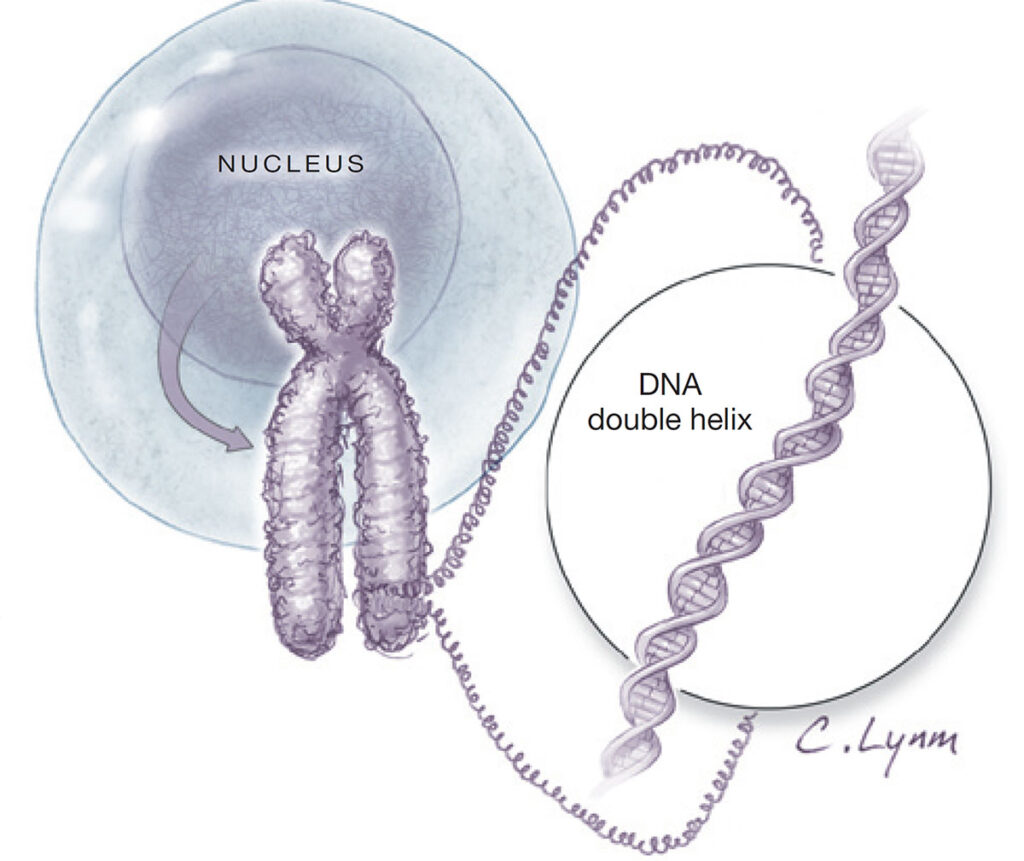

Genetics is the study of heritable changes in the nucleotide sequences that make up our genetic code. At the heart of this code lies DNA (see Figure 2.), the molecular blueprint that encodes the instructions for life itself. DNA is the fundamental hereditary material, enabling the transmission of traits from one generation to the next. Structurally, DNA consists of two long, twisting strands arranged in a double helix. Each strand is composed of repeating units called nucleotides, which are capable of storing genetic information.

Figure 2. Organization of genetic material in a human cell. DNA is tightly coiled into chromosomes, which are located inside the cell nucleus. The detailed inset shows the structure of the DNA double helix, composed of two twisted strands carrying genetic information. Sourced from Torpy et al. 2008.

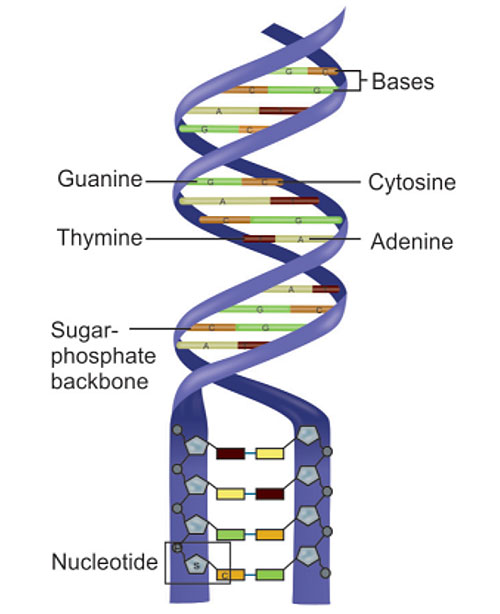

Every nucleotide includes a sugar (deoxyribose), a phosphate group, and one of four nitrogen-containing bases: purines (A – adenine, G – guanine) and pyrimides (C – cytosine, T – thymine). These bases pair in a specific, complementary manner (see Figure 3.): adenine pairs with thymine (A–T) and cytosine pairs with guanine (C–G). This base pairing is essential for accurate DNA replication and genetic transmission. In human cells, DNA is found in two locations. The vast majority of genetic material is located in the nucleus, while mitochondria contain their own small circular DNA, which is inherited maternally. Although the total length of DNA in a single human cell is estimated to be around one meter, it is compactly coiled and folded to fit within the microscopic nucleus. It is a remarkable example of biological engineering.

Figure 3. Structure of the DNA double helix. Sourced from Mattick 2004.

Segments of DNA that encode instructions for specific proteins are called genes. These are the basic units of heredity passed from parents to offspring and presented in every cell. The human genome contains approximately 20,000 to 25,000 genes, most of which are protein-coding. Each gene is composed of exons (coding sequences) and introns (noncoding sequences), together forming a DNA sequence that instructs the cell on how to produce particular proteins. Genes exist in different forms known as alleles. For any given gene, an individual typically inherits two alleles, one from each parent. These can be identical (making the individual homozygous) or different (heterozygous). In simple Mendelian inheritance, dominant alleles are expressed even when only one copy is present, whereas a recessive allele requires two copies to affect the phenotype (observable traits of an organism). However, most genes have more than two possible alleles, resulting in a range of heterozygous combinations. The specific composition of alleles in an individual constitutes genotype, while the observable characteristics or traits make up the phenotype.

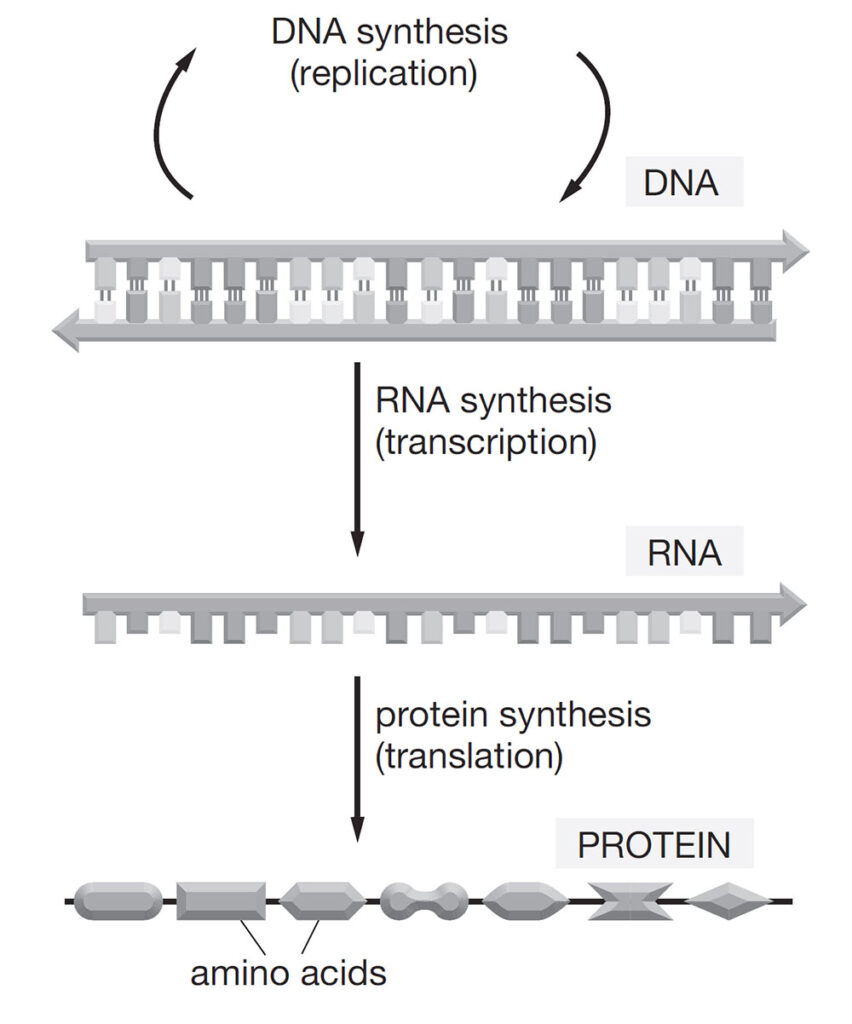

The flow of genetic information is governed by what is known as the central dogma of molecular biology: information is transcribed from DNA to messenger RNA (mRNA) and then translated from mRNA into proteins (Figure 4.). During translation, the mRNA sequence is read in triplets called codons, with 64 possible combinations that specify amino acids or signal the end of a protein chain. As already mentioned, only about 1.5% of the human genome encodes proteins. The remaining 98.5% consists of non-coding regions, once thought to be “junk DNA,” but now recognized as vital for regulation. These regions include regulatory elements and non-coding RNAs, which play essential roles in controlling gene expression and cellular behavior.

Figure 4. The central dogma of molecular biology. Genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein. DNA undergoes replication to duplicate itself. Through transcription, a strand of RNA is synthesized from the DNA template. The RNA sequence is then translated into a chain of amino acids, forming a protein that carries out cellular functions. Sourced from Lewis 2017.

Beyond the molecular mechanisms of gene expression, the organization of genetic material within the cell also plays a critical role. Within the cell nucleus, genes are organized into larger structures called chromosomes, compact packets of DNA and proteins that ensure efficient storage and accurate transmission of genetic material during cell division. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, for a total of 46. One chromosome in each pair is inherited from the mother, and the other from the father. Among these pairs, 22 are autosomes, while the 23rd pair consists of sex chromosomes: XX for females and XY for males. These chromosomes not only carry genes responsible for sexual development but also influence other physiological traits through genes unrelated to sex. The complete set of genetic material contained within an organism is referred to as its genome. In humans, the genome comprises all of the DNA distributed across the 23 pairs of chromosomes. These genomes are tightly packed within the microscopic nucleus of each cell, guiding everything from cell function to organismal development. The genome operates through three fundamental molecular systems often described as its three languages: DNA, which stores the instructions; RNA, which transmits them; and proteins, which execute them. Together, they form a dynamic, interconnected network that underlies all biological processes.

While genetics focuses on the sequence of DNA itself, epigenetics refers to changes in gene expression that occur without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This field was first classically defined by Conrad Waddington in the 1940s as “the study of the causal interactions between genes and their products that give rise to a phenotype.” Epigenetic mechanisms influence which genes are turned on or off, thereby shaping cellular identity, development, and disease susceptibility. The major epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation and histone modification. In DNA methylation, methyl groups attach to specific nucleotides, often silencing gene activity. Histone modifications, on the other hand, alter the structural proteins around which DNA is wound, affecting how tightly or loosely DNA is packed, thus influencing gene accessibility and expression. These changes can be stable and heritable through cell divisions, making epigenetic regulation a powerful mechanism in both development and disease.

Additionally, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) play a critical role in epigenetic regulation. Among these, microRNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNAs that regulate biological processes such as cell development, differentiation, and apoptosis. They act by cleaving target mRNA, promoting its degradation, or suppressing translation, and they may also modulate epigenetic processes indirectly. Another group, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), are involved in processes like cell cycle regulation, genomic imprinting, immune function, and embryonic stem cell differentiation. Although only partially characterized, lncRNAs have been shown to interact with chromatin-modifying complexes, influence transcriptional machinery, and bind to regulatory regions of DNA or RNA, thereby activating or repressing gene expression. Through these diverse actions, non-coding RNAs serve as key regulators of the epigenome, complementing the static instructions encoded in our DNA with dynamic, context-specific control.

The differences between species, and even between individuals of the same species, are not defined solely by the genes they possess, but more importantly by how those genes are regulated. It is the dynamic control of gene expression across time and space that determines biological diversity and complexity. Two main factors govern this regulation: genetics, which refers to the DNA sequence itself, and epigenetics, which influences how that sequence is read and expressed without changing the underlying code. Although every cell in the human body originates from a single fertilized egg and contains an identical DNA sequence, these cells differentiate into distinct types, such as neurons, muscle cells, or liver cells, each performing unique functions. This specialization is made possible by epigenetic mechanisms, which selectively activate or silence genes as needed. In this way, genetics provides the script, while epigenetics directs the performance. Together, they form the foundation of development, health, and individuality.

Resources:

Ahuja, M. S. Structure of DNA. In Talwar, P., ed. Manual of Cytokinesis in Reproductive Biology. JP Medical Ltd, 2014.

Gayon, J. From Mendel to epigenetics: History of genetics. Comptes Rendus Biologies, 2016, 339, 225-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crvi.2016.05.009

Lewis, R. (2017). Human genetics: The basics. 2017 (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Mattick, J. RNA regulation: a new genetics? Perspectives, 2004, 5, 316-323. http://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1321

Sharma, S.; Aazmi, O. Basics of epigenetics: It is more than simple changes in sequence that govern gene expression. Prognostic Epigenetics, 2019, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814259-2.00001-7

Torpy, J. M..; Lynm, C.; Glass, R. M. Genetics: the Basics. The Journal of American Medical Association, 2008, 299, 11, 1388. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.299.11.1388