How people perceive naturalness plays a key role in the acceptance of food technologies. The term “natural” is widely used in food marketing and everyday discussions, but there is no universally accepted definition of what makes food “natural”. Its interpretation is often shaped by consumer intuition rather than objective criteria. For instance, people perceive orange juice with added vitamin C as less natural than orange juice with removed vitamin C, even though both involve modifications to its original composition. Similarly, the use of E numbers for food additives reduces their perceived naturalness compared to when the same additives are listed without E numbers. This highlights how perceptions of naturalness are more about emotional response than scientific reasoning. Because of this subjectivity, the term “natural” is often used inconsistently. Different regulatory bodies interpret the term in various ways, and in many cases, it is used loosely to appeal to consumer preferences rather than to describe a specific production method. While many people associate “natural” with health, purity, or traditional methods, these assumptions can be misleading.

Firstly, natural does not always mean healthy. Many naturally occurring processes can be harmful. Toxins produced by molds, bacteria, or plants are entirely natural, yet they pose serious health risks. Similarly, certain wild mushrooms, unprocessed cassava, or spoiled food can contain dangerous compounds that are far from beneficial for human consumption. Secondly, very little of what we eat today is truly “natural” in the sense of being untouched by human intervention. If “natural” were defined as food created entirely by nature, without modification, then most of our diet would not qualify. Modern agriculture, including livestock farming, is not natural. It has been shaped by thousands of years of selective breeding, artificial watering, soil fertilization, and disease control. Even fruits and vegetables (e.g. Figure 1.) have undergone genetic changes over centuries to increase yield, taste, and resilience. Another common perception is that natural equals traditional, meaning food produced using home cooking, fermentation, or traditional farming techniques. While these methods have been passed down through generations, they are still forms of food processing. More importantly, innovation in food technology has always played a crucial role in food security, safety, and sustainability. Techniques like plant breeding, mechanized irrigation, pasteurization, sterilization, refrigeration, and the use of veterinary medicine have greatly improved food quality and safety. Without these advancements, our food system would be far less efficient and more vulnerable to disease, spoilage, and environmental challenges. Ultimately, “natural” does not always mean better. While many associate natural food with higher quality and purity, it is often scientific advancements that ensure food is safer, more nutritious, and more sustainable. This leads to an important question: Where does cultivated meat fit into this debate? If traditional farming is no longer truly “natural,” can cultivated meat be seen as a logical extension of human progress in food production rather than a deviation from nature?

Figure 1. The image shows a comparison between early maize (left) and modern cultivated corn (right).

One of the key arguments in the debate about cultivated meat is whether it can be considered natural. While some view the laboratory setting as inherently artificial, the process itself follows the same biological mechanisms that take place inside every living organism. At its core, cell growth, differentiation, and renewal are natural processes. Every cell in the body undergoes a continuous cycle of growth, division, aging, and programmed cell death (apoptosis). For example, human skin cells regenerate every two to three weeks, demonstrating the body’s ability to renew and replace tissue in a controlled manner. Muscle tissue, which is the primary component of meat, is generally stable and consists of multinucleated postmitotic muscle fibers that do not divide. However, muscle tissue has a natural ability to repair and regrow itself, largely thanks to special cells called satellite cells. These cells can be activated by injury or extensive physical activity, allowing for the gradual repair of muscle tissue. In mammals, daily wear and tear of muscles is repaired at a rate of approximately 1–2% per week. Similarly, fat cells also undergo natural renewal. Research shows that approximately 10% of fat cells are replaced annually, regardless of age or body mass index. This demonstrates that even tissues considered relatively stable are constantly undergoing cellular turnover and regeneration.

The foundation of cultivated meat production lies in the natural ability of cells to grow and divide. While cells in different parts of the body behave differently, they are fundamentally the same, sharing the same DNA but following specific genetic instructions that determine their function. Cultivated meat utilizes these innate biological mechanisms, replicating the natural processes of cell growth and differentiation in a controlled environment rather than inside an animal. This approach is not an artificial intervention but rather a precise optimization of what already occurs in nature. By providing cells with the right conditions (nutrients, signals, and a suitable environment), they grow as they would naturally. The key difference is that this process happens without requiring the entire animal. By harnessing biological principles that govern natural tissue growth, cultivated meat production offers a sustainable and ethical alternative that remains deeply rooted in nature itself.

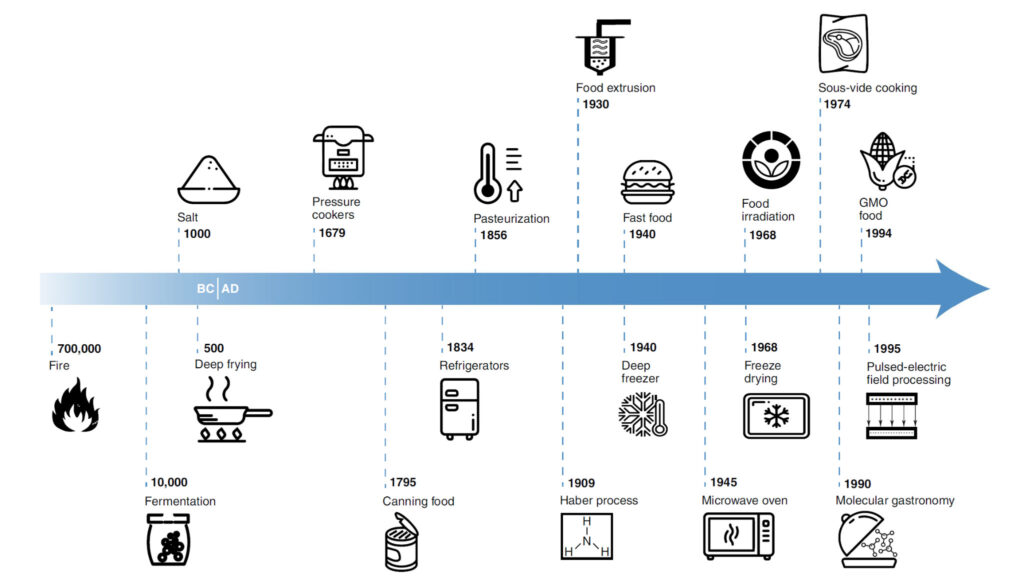

Perceptions of naturalness play a key role in the acceptance of food technologies. In Western countries, the concept of “natural” is almost universally associated with positive emotions. As a result, most consumers place great importance on naturalness in food, often assuming that natural foods are inherently healthier, tastier, and more environmentally friendly. Technological progress has fundamentally shaped what we eat today, as illustrated in Figure 2. It is important to recognize that many of the foods we consume today are not “natural” in the strictest sense of the word. Modern food production often involves intensive processing, including the addition of synthetic chemicals and additives to enhance flavor, extend shelf life, and improve texture. Even foods that appear untouched by technology, such as fruits and vegetables, have undergone millennia of selective breeding and domestication, drastically altering their original characteristics. The crops we now consider common and natural were once smaller, less palatable, and contained more seeds. For example, wild peaches were originally bitter and low in sugar, whereas modern cultivated varieties have been selectively bred to eliminate bitterness and maximize sweetness. This same principle applies to many other crops, including corn, bananas, and tomatoes, which have been shaped by human intervention over thousands of years. These examples highlight an important reality that many of the foods we perceive as “natural” are, in fact, the product of extensive human modification. Understanding this should encourage us to rethink our perception of naturalness, particularly in the context of modern agriculture and food production. Rather than focusing on whether a food is strictly “natural,” we should consider its safety, sustainability, and other benefits that cultivated meat is well-positioned to meet.

Figure 2. A timeline of key innovations in food technology. Sourced from Siegrist & Hartmann 2020a.

Resources:

Li, Y.; Cao, K.; Zhu, G.; Fang, W.; Chen, Ch.; Wang, X.; Zhao, P.; Guo, J.; Ding, T.; Guan, Q.; Guo, W.; Fei, Z.; Wang, L. Genomic analyses of an extensive collection of wild and cultivated accessions provide new insights into peach breeding history. Genome Biology, 2019, 20, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1648-9

Pondeljak, N.; Lugović-Mihič, L.; Tomić, L.; Parać, E.; Pedić, L.; Lazić-Mosler, E. Key Factors in the Complex and Coordinated Network of Skin Keratinization: Their Significance and Involvement in Common Skin Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024, 25, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010236

Schmidt, M.; Schüler, S. C.; Hüttner, S. S.; von Eyss, B.; von Maltzahn, J. Adult stem cells at work: regenerating skeletal muscle. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2019, 76, 2559–2570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03093-6

Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, Ch. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nature Food, 2020a, 1, 343-350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0094-x

Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, Ch. Perceived naturalness, disgust, trust and food neophobia as predictors of cultured meat acceptance in ten countries. Appetite, 2020b, 155, 104814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104814

Spalding, K. L.; Arner, E.; Westermark, P. O.; Bernard, S.; Buchholz, B. A.; Bergmann, O.; Blomqvist, L.; Hoffstedt, J.; Näslund, E.; Britton, T.; Concha, H.; Hassan, M.; Rydén, M.; Frisén, J.; Arner, P. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature Letters, 2008, 453, 783-787. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06902