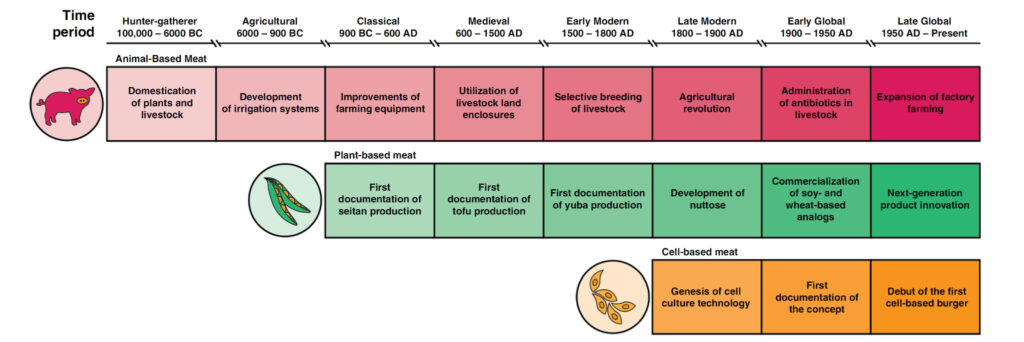

Figure 1. The history and evolution of animal-based, plant-based and cultivated meat approaches to meat production. Sourced from Rubio et al. 2020.

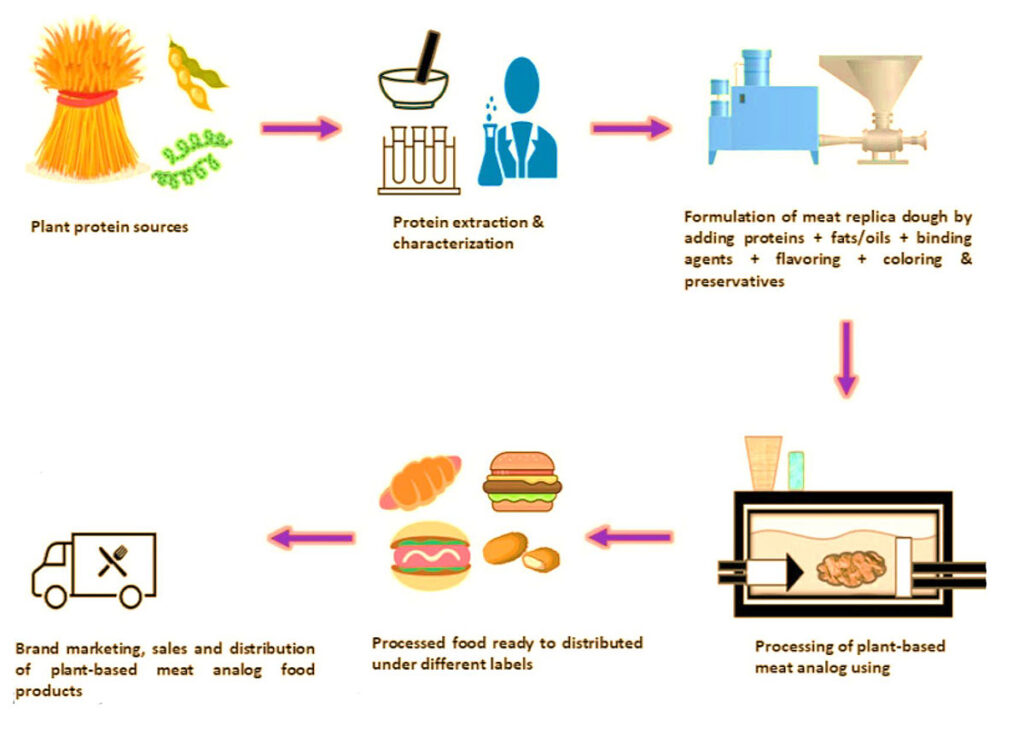

Plant-based protein alternatives can be divided into two main categories: traditional and novel. Traditional sources, such as tofu, tempeh, and seitan, have been consumed for centuries and are typically made using simple fermentation or coagulation processes. In contrast, novel plant-based meat alternatives often rely on industrial processing to achieve a texture and taste similar to conventional meat. The production of these modern alternatives involves multiple stages of processing (illustrated in Figure 2.), including protein isolation and functionalization (e.g., hydrolyzation) to enhance protein properties. The formulation stage combines plant proteins with additional ingredients such as fats, flavor enhancers, and color additives. Finally, the mixture undergoes mechanical processing, including stretching, kneading, pressing, folding, and extrusion, to create a meat-like texture. One of the key advantages of plant-based proteins is their lower cost at the raw material level. In the United States, the farm-gate prices of soy, wheat, and pea proteins are 3.8–12.7 times lower than the prices received for cattle, pigs, and broilers. However, despite these low input costs, the final retail price of plant-based alternatives is significantly influenced by post-harvest processing. While only about 50% of the retail cost of beef is attributed to processing, approximately 94.3% of the final cost of plant-based protein products stems from these additional processing steps. This includes the incorporation of plant-based fats, texturizing agents, and other additives, which contribute to both the cost and the sensory properties of the final product.

Figure 2. Multiple processing stages involved in the production of modern plant-based meat alternatives. Sourced from Singh et al. 2021 with modifications.

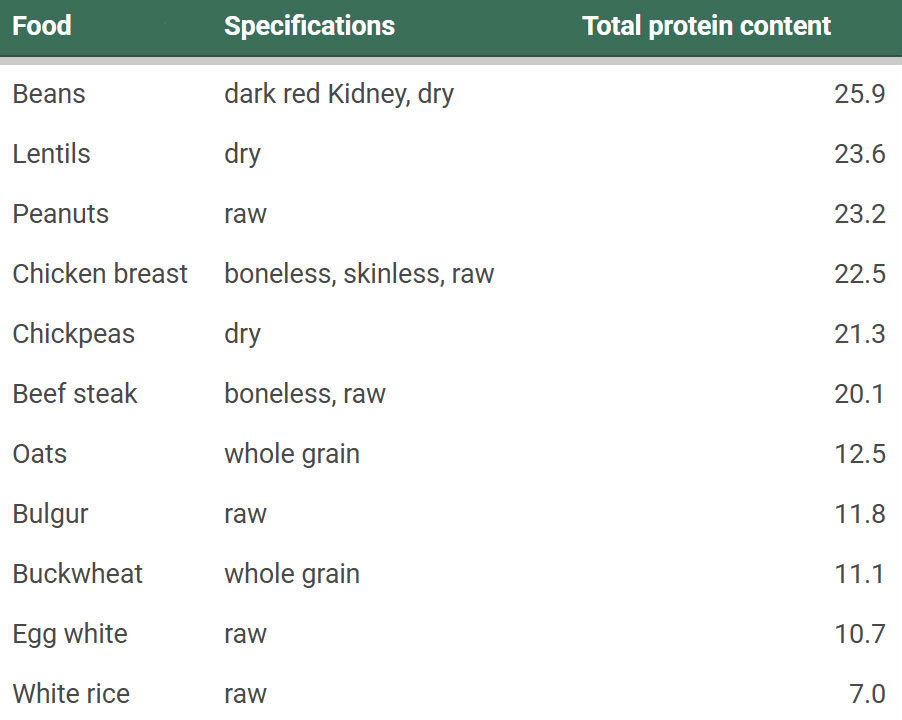

The quality of a protein source is not uniform, even within a single category. The nutrient composition of the same plant species can vary due to differences in soil composition, climate conditions, rainfall levels, geographic latitude and altitude, farming methods, and specific plant varieties or cultivars. Protein quality is assessed based on multiple factors, including total protein content, balance and relative amounts of essential amino acids, digestibility, bioavailability, and bioactivity. The protein content values for various foods can be found in Table 1. A commonly used method for measuring total protein content is the Kjeldahl method, which remains a standard in the food industry and regulatory laboratories. This method estimates protein content by measuring total nitrogen, assuming that all nitrogen originates from proteins. However, it does not distinguish between nitrogen derived from actual protein and nitrogen from other compounds, making it a potentially misleading measure of protein quality. Despite its limitations, the Kjeldahl method is still widely used, and its results appear on product labels, often giving an incomplete picture of a product’s true nutritional value.

Table 1. Total protein content in different animal-based and plant-based foods. Values sourced from USDA.

One of the main differences between animal and plant proteins lies in their amino acid profile. Most plant-based proteins are nutritionally incomplete, meaning they lack one or more essential amino acids in sufficient quantities. Exceptions include quinoa, soy, and buckwheat, which contain a more balanced amino acid profile, although often in lower amounts than animal proteins. Due to these limitations, achieving a well-balanced amino acid profile from plant sources typically requires protein complementation. This strategy involves combining different plant proteins to compensate for deficiencies. A common approach is to pair legume proteins (which are low in sulfur-containing amino acids but high in lysine) with cereal proteins (which are high in sulfur-containing amino acids but low in lysine), creating a more nutritionally complete protein source.

Building on the discussion of protein quality, another critical factor in assessing protein sources is digestibility. Protein digestibility is often evaluated using the protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) or the more accurate digestible indispensable amino acid score (DIAAS). Compared to animal-based proteins, many plant proteins tend to have lower digestibility, with the exception of soy protein, which demonstrates relatively high digestibility among plant sources. Additionally, the processing technologies used to create plant-based alternatives may result in the formation of structures that negatively affect protein digestion. Some processing methods alter protein conformation, making it more resistant to enzymatic breakdown, while others introduce interactions with fiber and other food components that further reduce digestibility.

In addition to digestibility, bioavailability, the extent to which nutrients are absorbed and utilized by the body, is another important factor to consider. Many plant proteins contain structures that decrease nutrient bioavailability due to resistance to proteolysis, unfavorable protein conformations, and the presence of antinutritional factors (see below). These compounds can interfere with the absorption of essential nutrients, further limiting the efficiency of plant-based protein sources when compared to their animal-based counterparts.

Both animal-based and plant-based foods contain essential micronutrients such as vitamin B12, iron, calcium, potassium, magnesium, and zinc, but plant-based sources often have lower bioavailability. While these nutrients are crucial for overall health, with iron, zinc, and vitamin B12 playing particularly important roles in brain function and cognitive development, their absorption from plant-based foods can be less efficient. As a result, the bioavailability of zinc and non-heme iron from plant-based foods is 1.7–2 times lower than from animal sources. This means that even when plant-based diets provide adequate amounts of these nutrients, the body may not absorb and utilize them as efficiently, potentially increasing the risk of deficiencies.

Many plant foods also contain antinutritional compounds, such as fiber, phytates, tannins, saponins, and phenolic compounds, which can interfere with digestion and nutrient absorption. They are naturally produced by plants as a defence mechanism. The main health impact of antinutritional factors in plant-based meat alternatives is their ability to reduce nutrient bioavailability. Additionally, these compounds can affect the sensory qualities of plant-based meat products, often contributing to unpleasant flavors such as bitterness. Phytic acid, commonly found in grains and legumes, binds to essential minerals such as iron, zinc, and calcium, making them unavailable for absorption by the body. This can lead to mineral deficiencies, which may impact cognitive function, immune health, and bone development. In some cases, excessive intake of antinutrients has been associated with maldigestion, inflammation, gut dysfunction, and even autoimmune responses. However, food processing techniques can significantly reduce antinutrient levels, thereby improving protein digestibility and increasing mineral bioavailability. Methods such as soaking, sprouting, fermenting, and heat treatment can help break down these compounds, making plant-based proteins more nutritionally comparable to animal-derived sources.

The taste and texture of plant-based meat alternatives play a critical role in consumer acceptance. Achieving a flavor and appearance similar to conventional meat requires a complex formulation of ingredients and additives, including plant-based fats, flavor enhancers, and texturizing agents. These products often undergo multiple processing stages to replicate the structure and mouthfeel of meat, classifying them as ultra-processed foods. While these modifications improve sensory appeal, they may also raise concerns about the nutritional quality and health implications of heavily processed food products. However, there is a growing discussion about the limitations of this classification, as it focuses solely on the degree of processing rather than nutritional value or intended function. Some experts argue that not all ultra-processed foods are nutritionally poor and that the term can be misleading when applied to purposefully processed foods like plant-based meat alternatives. These products are developed to offer an option that is often lower in saturated fat, cholesterol-free, and higher in fiber.

Unlike plant-based replacements, cultivated meat is not an imitation, it is real meat at the cellular level. Rather than attempting to mimic meat using alternative ingredients, cultivated meat is produced by growing animal cells in a controlled environment, resulting in a product that is nutritionally equivalent to conventional meat. This distinction is essential in understanding the fundamental differences between animal proteins, plant-based substitutes, and the emerging category of cultivated meat. One key advantage of cultivated meat is also its potential for personalization/customerization. As the technology advances, it may allow for tailored nutrient profiles, optimized fat compositions, or even adjustments to texture and taste to meet individual dietary preferences. While some critics argue that cultivated meat undergoes processing, it does not fall into the same category as ultra-processed foods like many plant-based meat alternatives, which often contain numerous additives and structural modifications. While it does not fit within a strict vegan framework, it offers a compromise for those who prioritize animal welfare but still recognize the nutritional benefits of animal-derived proteins. This nutritional, ethical and environmental dimension sets cultivated meat apart from both traditional meat and plant-based alternatives. As consumer preferences continue to evolve, cultivated meat stands as a promising solution that bridges the gap between sustainability, ethics, and dietary needs.

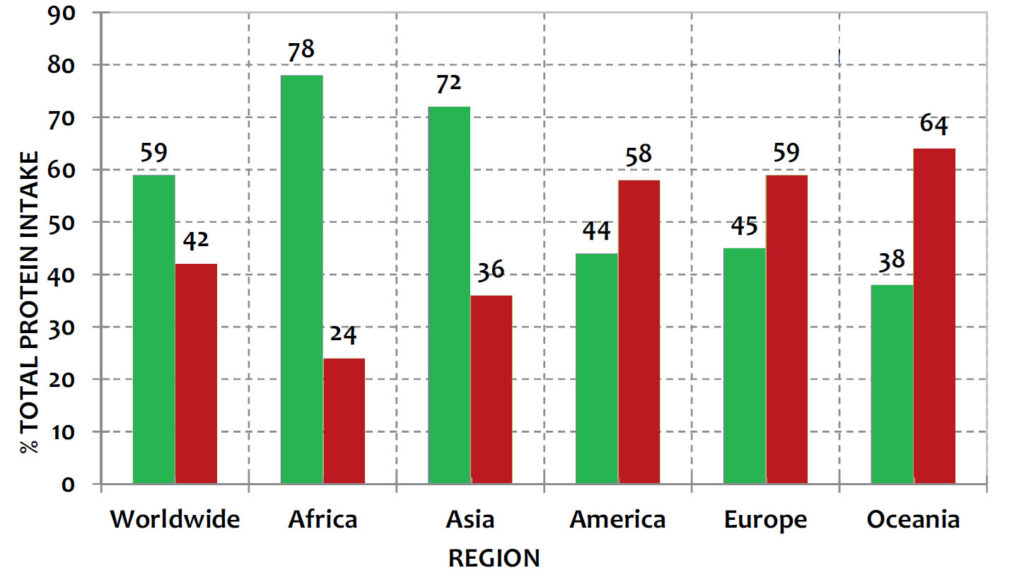

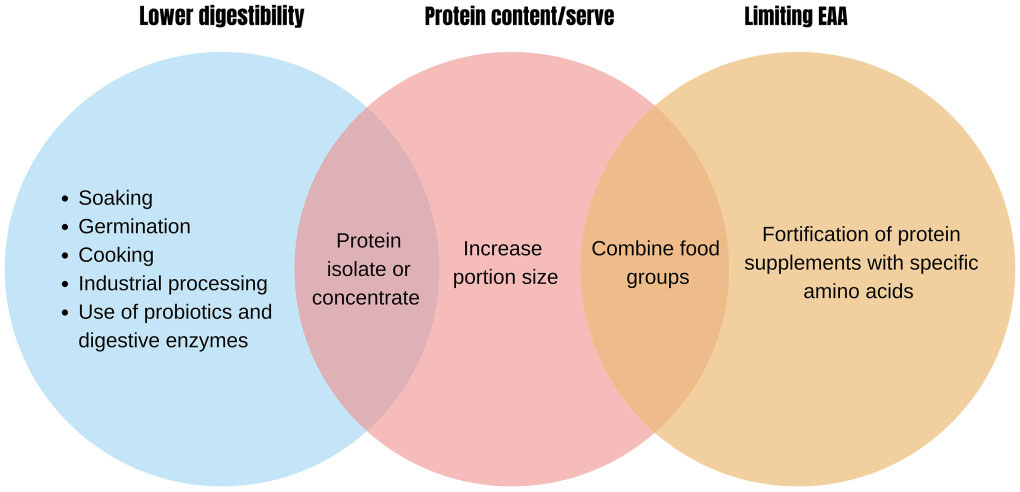

Both plant-based and animal-derived proteins play a role in meeting the growing global demand for dietary protein. Currently, 60% of dietary protein comes from plant sources and 40% from animal sources, reflecting a diverse approach to nutrition. However, this distribution varies by region, with some areas relying more heavily on plant-based proteins due to dietary habits, economic factors, or availability of animal products (Figure 3.). While plant-based proteins are often considered more sustainable and ethical, nutrient content, digestibility, and bioavailability differ significantly between the two sources (see Figure 4, where solutions to the deficiencies of plant-based foods are proposed). Humans have evolved as omnivores, with a digestive system optimized for a high-quality, nutrient-dense diet, in contrast to herbivores, which possess specialized adaptations for processing fibrous plant materials. Unlike cows or pandas, which rely on fermentation and have extended digestive tracts, humans lack the necessary enzymes and gut adaptations to extract sufficient nutrients from a strictly plant-based diet. Even when compared to their closest relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas, humans have a proportionally larger small intestine (70% vs. 15–25%) and a reduced colon, favoring the digestion of energy-dense foods like meat. This anatomical distinction highlights the historical significance of animal-derived nutrients in human evolution.

Figure 3. The worldwide proportion of protein consumption derived from plant (green) versus animal (red) sources. Sourced from Singh et al. 2021 with modifications.

Meat remains a key dietary component due to its high density of essential nutrients and superior bioavailability. However, its consumption varies widely across the globe. In regions with low meat intake, such as South Asia (7g/day) and Sub-Saharan Africa (24g/day), undernutrition is more prevalent, leading to stunted physical and cognitive development, which can hinder economic progress. While reducing global meat consumption is often proposed as a sustainability strategy, drastic reductions could pose nutritional risks, especially in vulnerable populations where access to alternative nutrient sources is limited. If meat intake is restricted, alternative sources must compensate for its essential nutrients, either through a carefully planned diet, fortification, or supplementation. However, this is not always straightforward due to economic constraints, dietary habits, food intolerances (e.g., gluten, soy, or pea protein), and gaps in nutritional awareness. In regions where meat consumption is already low, further reductions could exacerbate malnutrition and health disparities.

Figure 4. Possible solutions to the deficiencies of plant-based foods. Sourced from Nichele et al. 2022.

Although plant-based proteins are easier to produce compared to animal-derived proteins, they are not always nutritionally equivalent. Most plant proteins lack sufficient amounts of essential amino acids, making them incomplete as standalone dietary protein sources. This poses additional challenges in regions where meat intake is already limited, as relying solely on plant-based protein requires careful dietary planning to ensure adequate amino acid intake. At the same time, the inefficiency of animal protein production, which requires 6 kg of plant protein to produce just 1 kg of meat protein, highlights the substantial loss of protein and energy during the conversion process. This inefficiency underscores the critical importance of exploring alternative protein sources to ensure food security. Cultivated meat emerges as a potential solution, offering a nutritionally authentic and efficient protein source that aligns with both sustainability goals and human dietary needs. By providing a high-quality alternative without the ethical and environmental drawbacks, cultivated meat has the potential to support global nutrition while reducing the environmental footprint of meat production.

Resources:

Baig, M. A.; Ajayi, F. F.; Hamdi, M.; Baba, W.; Brishti, F. H.; Khalid, N.; Zhou, W.; Maqsood, S. Recent Research Advances in Meat Analogues: A Comprehensive Review on Production, Protein Sources, Quality Attributes, Analytical Techniques Used, and Consumer Perception. Food Reviews International, 2025, 41, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2024.2396855

Good Food Institute & Physicians Association for Nutrition. 2025. Where does plant-based meat fit in the UPF conversation? Available online: https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:EU:39626559-1082-4d21-92a7-d71ade12fa78?viewer%21megaVerb=group-discover

Gorbunova, N. A. Assessing the role of meat consumption in human evolutionary changes. A review. Theory and practice of meat processing, 2024, 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.21323/2414-438X-2024-9-1-53-64

He, J.; Evans, N. M.; Liu, H.; Shao, S. A review of research on plant-based meat alternatives: Driving forces, history, manufacturing, and consumer attitudes. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2020, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12610

Kołodziejczak, K.; Onopiuk, A.; Szpicer, A.; Poltorak, A. Meat Analogues in the Perspective of Recent Scientific Research: A Review. Foods, 2022, 11, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11010105

Langyan, S.; Yadava, P.; Khan, F. N.; Dar, Z. A.; Singh, R.; Kumar, A. Sustaining Protein Nutrition Through Plant-Based Foods. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2022, 8, 772573. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.772573

Leroy, F.; Smith, N. W.; Adesogan, A. T.; Beal, T.; Iannotti, L.; Moughan, P. J.; Mann, N. The role of meat in the human diet: evolutionary aspects and nutritional value. Animal Frontiers, 2023, 13, 2, 11-18. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfac093

Nichele, S.; Phillips, S. M.; Boanventura, B. C. B. Plant-based food patterns to stimulate muscle protein synthesis and support muscle mass in humans: a narrative review. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 2022, 47, 700-710. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2021-0806

Our World in Data, Per capita sources of protein, World, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-sources-of-protein?country=~OWID_WRL (accessed 21 March 2025)

Rubio, N. R.; Xiang, N.; Kaplan, D. L. Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production. Nature communications, 2020, 11, 6276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20061-y

Singh, M.; Trivedi, N.; Enamala, M. K.; Kuppam, Ch.; Parikh, P.; Nokolova, M. P.; Chavali, M. Plant based meat analogue (PBMA) as a sustainable food: a concise review. European Food Research and Technology, 2021, 247, 2499–2526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-021-03810-1

Shankaran, P. I.; Kumari, P. Nutritional Analysis of Plant-Based Meat: Current Advances and Future Potential. Applied Science, 2024, 14, 10, 4154. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14104154

Tyndall, S. M.; Maloney, G. R.; Cole, M. B.; Hazell, N. G.; Augustin, M. A. Critical food and nutrition science challenges for plant-based meat alternative products. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2024, 64, 3, 638-653. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2107994

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov (accessed 20 March 2025)

Wang, S.; Zhao, M.; Fan, H.; Wu, J. Peptidomics Study of Plant-Based Meat Analogs as a Source of Bioactive Peptides. Foods, 2023, 12,1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12051061

Xie, Y.; Cai, L.; Zhao, D.; Liu, H. Real meat and plant-based meat analogues have different in vitro protein digestibility properties. Food Chemistry, 387, 4, 132917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132917

Zhou, H.; Hu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; McClements, D. J. Digestibility and gastrointestinal fate of meat versus plant-based meat analogs: An in vitro comparison. Food Chemistry, 2021, 364, 130439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130439