Proteins are fundamental components of the human diet and are essential for life. They are involved in nearly every biological process, from building and maintaining body tissues, such as muscles, skin, and organs, to supporting the immune system, synthesizing enzymes and hormones, and transporting nutrients and oxygen throughout the body. Every cell in the human body relies on proteins to function properly, making them indispensable for maintaining health and vitality. Animal-based foods such as meat, eggs, and dairy typically provide high-quality, complete proteins in optimal ratios for human needs. Certain plant-based sources can also contribute significantly to overall protein intake, especially when properly combined.

Proteins are macromolecules composed of long chains of amino acid subunits, and they are classified as essential macronutrients, vital for human survival, health, and reproduction. These intricate molecules are responsible for a wide range of biological roles, from structural support to enzymatic catalysis and immune defense. The human body depends on a continuous turnover of proteins to maintain tissue integrity and function, making the adequate supply and proper utilization of dietary protein critically important. The human proteome (entire set of proteins) comprises a vast array of proteins constructed from 21 different amino acids, each linked together by peptide bonds formed between the amino group of one amino acid and the carboxyl group of another. Depending on the number of amino acids bound in the chain, we distinguish between oligopeptides (2 to 10 amino acids), polypeptides (11 to 100 amino acids), and full proteins (more than 100 amino acids). While the number of amino acids is important, it is the specific order and composition of these building blocks that ultimately determine the structure, properties, and biological function of each protein. These protein structures serve a multitude of indispensable functions in the body, including biochemical catalysis (as enzymes), structural support (as collagen and keratin), movement (actin and myosin), transport (hemoglobin and albumin), regulation of cellular processes (hormones and signaling molecules), immune protection (antibodies), and storage (ferritin, casein).

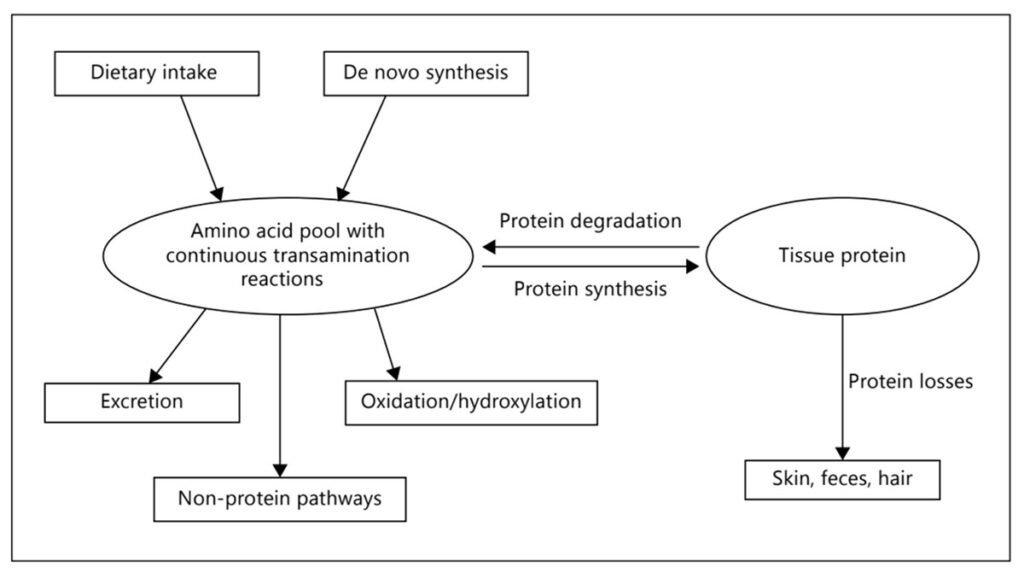

When proteins are ingested through food, they are hydrolyzed in the gastrointestinal tract into amino acids and small peptides. These breakdown products are then absorbed and either used for de novo protein synthesis or serve as precursors in the biosynthesis of critical compounds such as nucleic acids, hormones, and vitamins. Within the human body, proteins are in a constant state of turnover (illustrated in Figure 1.), being broken down and rebuilt in a dynamic balance that reflects physiological needs, tissue repair, and metabolic function.

Figure 1. Protein turnover. Sourced from Goudoever et al. 2014.

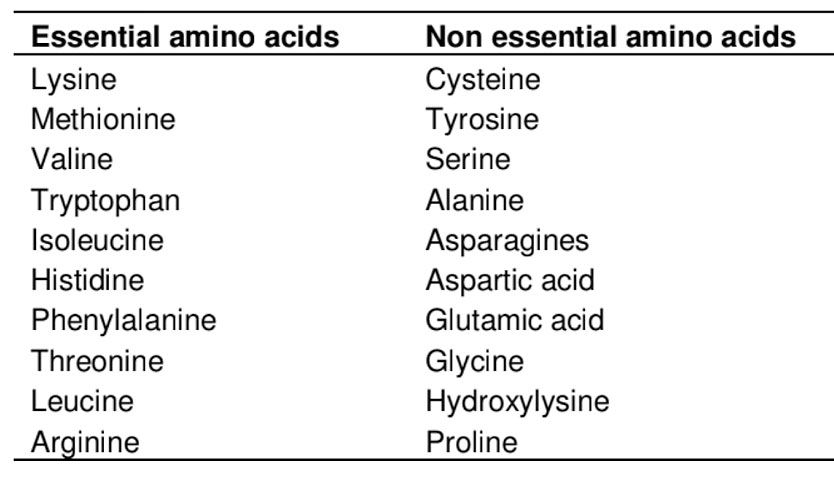

Amino acids are the fundamental building blocks of proteins. These organic compounds contain both an amino group and a carboxylic acid group. Although over 300 amino acids exist in nature, only 21 are used in the synthesis of proteins in the human body. These proteinogenic amino acids form the basis of the human proteome and are essential not only for protein formation but also for a wide range of vital biological processes. All mammalian proteins are composed of α-amino acids, characterized by a central α-carbon atom bonded to a carboxyl group, an amino group, and a unique side chain. Based on their metabolic role, amino acids can be classified as essential, non-essential (see Table 1.), or conditionally essential. Essential amino acids cannot be synthesized by the human body and must be obtained through the diet, while non-essential amino acids can be produced endogenously. Conditionally essential amino acids are amino acids that are normally non-essential (the body can synthesize them), but under certain conditions, the body’s demand exceeds its ability to produce them, making them essential in the diet. Their availability and balance are crucial. Deficiencies can impair protein synthesis, while excesses may lead to health issues such as oxidative stress, neurological dysfunction, or cardiovascular disease. Maintaining optimal amino acid homeostasis is therefore vital for efficient nutrient utilization, lean tissue development, and overall health.

Table 1. Classification of amino acids. Sourced from Akram et al. 2011.

Human protein needs are influenced by several individual factors, including body weight and composition, physiological state (such as growth, pregnancy, or lactation), physical activity level, and the presence of pathological conditions. Because protein plays a foundational role in growth, repair, and metabolic regulation, daily intake must align with these demands to ensure proper bodily function. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein, established by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine (U.S.), is set at 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day for healthy adults. This recommendation reflects the minimum intake required to meet the needs of 97% of healthy individuals. However, growing evidence suggests that this baseline may not be optimal for everyone. Higher protein intakes, beyond the RDA, may support better health outcomes, particularly in older adults, where increased protein consumption is linked to the prevention of sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle mass), maintenance of bone mineral density, and reduced risk of fractures. In addition, higher protein diets have been associated with better appetite regulation, weight management, and enhanced athletic performance, highlighting the importance of adjusting protein intake to suit individual life stages and health goals.

Meeting daily protein requirements is not solely a matter of quantity. Protein quality plays a critical role in determining how effectively the body can utilize ingested proteins. The nutritional quality of proteins is highly heterogeneous and depends on several key factors, including their amino acid composition, digestibility, and bioavailability. One of the primary indicators of protein quality is the amino acid profile. Complete proteins provide all nine essential amino acids: histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine. Animal-derived proteins generally offer a complete amino acid profile, whereas many plant-based sources (such as cereals and legumes) may be deficient in one or more essential amino acids. This makes complementary pairing of plant proteins important in vegetarian and vegan diets.

Another crucial factor is digestibility, which refers to the proportion of protein (measured as nitrogen) that is absorbed by the body after ingestion. During digestion, proteins are broken down into amino acids or small peptides that are absorbed through the intestinal wall (enterocytes) into the bloodstream and used for new protein synthesis or other physiological functions. To evaluate protein quality, international health organizations recommend two standardized scoring systems. Protein digestibility corrected amino acids score (PDCAAS) is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). This method evaluates both the amino acid profile and the digestibility of a protein source. Digestible indispensable amino acids score (DIAAS) is recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). This newer method provides a more accurate picture by measuring the digestibility of individual essential amino acids at the end of the small intestine.

Finally, bioavailability (how well nutrients are released from food, absorbed in the gut, and transported in the bloodstream) is another essential aspect of protein quality. Even proteins with a high amino acid content may have low nutritional value if they are poorly digested or absorbed. Animal-based proteins typically have higher bioavailability than plant-based proteins due to differences in structure and the presence of antinutritional factors in plants. Moreover, food processing (e.g. heating or chemical treatment) can further affect protein structure, sometimes reducing digestibility and the availability of key amino acids. In summary, evaluating protein sources requires a holistic view, taking into account not just the amount of protein, but also the completeness of the amino acid profile, digestibility, and bioavailability. All contribute to the true nutritional value of the protein consumed.

Beyond general protein content, the concentration and balance of indispensable (essential) amino acids vary significantly between animal- and plant-based food sources. Studies have shown that meat and fish products consistently contain higher levels of total essential amino acids compared to plant-based products. These amino acids are present in optimal ratios for human nutrition and are readily bioavailable, making meat an efficient and complete source of dietary protein. The explanation for this difference lies, in part, in the natural food chain. Plants absorb inorganic nitrogen and minerals from the soil and synthesize proteins, which often lack one or more essential amino acids or contain them in suboptimal ratios. When herbivores consume plants, their specialized digestive systems allow them to break down and reassemble these plant proteins into a more balanced amino acid profile. These are stored as animal proteins in muscle tissue, milk, or eggs. Carnivores and omnivores, including humans, then consume these animal-based foods and benefit from this pre-digested, metabolically efficient form of nutrients. In this way, meat provides amino acids that are more aligned with human physiological needs, reducing the metabolic burden of processing and transforming them.

In this context, cultivated meat represents a significant innovation in food technology, offering a high-quality, ethical, and sustainable alternative to traditional meat. Although it does not come from a slaughtered animal, it is still biologically equivalent to meat and therefore has the potential to provide high-quality protein with an amino acid profile comparable to that of conventional meat. The nutritional composition of cultivated meat can be influenced by factors such as the formulation of the cultivation medium used during production. By adjusting components like amino acids, vitamins, and growth factors, it is possible to modulate the nutritional content. This customization may allow for the enhancement of specific nutritional attributes, potentially leading to improved health benefits. This makes cultivated meat a promising solution for meeting human amino acid requirements without compromising on health or nutritional quality. However, these areas require further research, current data are limited. Therefore, ongoing studies are essential to fully understand and optimize the nutritional impact of cultivated meat.

Proteins and amino acids are indispensable for maintaining health, supporting growth, and enabling virtually every physiological function in the human body. As both a structural and functional cornerstone of life, adequate protein intake, in both quantity and quality, is essential for achieving optimal nutrition across all life stages. While animal-based proteins remain a gold standard for completeness and bioavailability, plant-based sources and novel protein technologies continue to expand our dietary options. Among these innovations, cultivated meat stands out as a promising solution that bridges the gap between nutritional adequacy, ethics, and sustainability. By offering a protein source with the potential to match the amino acid profile of conventional meat, while reducing concerns associated with traditional animal farming, cultivated meat could reshape the way we meet our dietary needs in the future. As our understanding of protein digestion, amino acid metabolism, and food innovation continues to evolve, the focus must remain on evidence-based strategies that support both individual health and planetary well-being. With continued research and responsible development, we can ensure that future protein sources, whether from animals, plants, or cells, nourish the world effectively, sustainably, and equitably

Resources:

Beaudry, K. M.; Binet, E. R.; Collao, N.; De Lisio, M. Nutritional Regulation of Muscle Stem Cells in Exercise and Disease: The Role of Protein and Amino Acid Dietary Supplementation. Frontiers in Physiology, 2022, 13, 915390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.915390

Huang, S.; Wang, L. M.; Sivendiran, T.; Bohrer, B. M. Review: Amino acid concentration of high protein food products and an overview of the current methods used to determine protein quality. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2017.1396202

Fraeye, I.; Kratka, M.; Vandenburgh, H.; Thorrez, L. Sensorial and Nutritional Aspects of Cultured Meat in Comparison to Traditional Meat: Much to Be Inferred. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2020, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.00035

López-Pedrouso, M.; Lorenzo, J. M.; Zapata, C.; Franco, D. Proteins and amino acids. In Innovative Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing, Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds. Elsevier, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814174-8.00005-6

van Goudoever, J. B.; Vlaardingerbroek, H.; van den Akker, Ch. H.; de Groof, F.; van der Schoor, S. R. D. Amino Acids and Proteins. World Review of Nutrition and Diabetics, 2014, 110, 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358458

Wu, G. Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids, 2009, 37, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-009-0269-0