Efficient regulatory frameworks play a pivotal role in enabling food innovation and ensuring timely market access. As the global demand for sustainable alternatives continues to grow, products such as plant-based proteins, fungal biomasses, and cultivated meat have already gained approval in several jurisdictions. However, despite these advances elsewhere, such alternatives remain largely inaccessible within the European Union due to pending regulatory approvals. Notably, a systematic and comparative legal approach to cultivated meat regulation has not yet been adopted. Instead, each jurisdiction tends to evaluate cultivated meat on a case-by-case, product-by-product basis. While the general regulatory logic appears broadly similar across different countries, notable differences exist in the implementation of these frameworks.

In Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand, companies are encouraged to engage in private discussions with the regulatory authority before submitting their applications. In the United States, consultations occur between the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the applicant, though it remains unclear to what extent such discussions take place prior to formal dossier submission. By contrast, the European Union takes a more rigid approach: no private consultations occur between EFSA and the applicant regarding the specifics of an application. Interactions are limited to general procedural matters and exclude any EFSA staff who may later be involved in evaluating the application. Another signifi cant divergence lies in the scope of assessment. Regulatory frameworks in Singapore and the United States focus primarily on scientific risk management, particularly food safety in relation to toxicity and allergenicity. In contrast, both the EU and Australia allow for a broader range of considerations beyond purely scientific assessments. Still, the Australian and New Zealand regulatory process for cultivated meat remains largely centered on scientific risk evaluation.

European Union

In the European Union (EU), cultivated meat is legally classified as a novel food, specifically within the subcategory of novel proteins. As such, it is subject to the regulatory requirements outlined in Regulation (EU) 2015/2283, which mandates pre-market approval before any novel food can be sold within the Union. Once a product is approved and included in the Union List of Novel Foods, it can be legally marketed across all EU Member States. According to Article 3 of the regulation, a novel food is defined as any food that was not consumed to a significant degree by humans within the Union before 15 May 1997. The regulation outlines ten categories of novel foods and establishes a centralized authorization process. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is responsible for conducting the safety evaluation of applications submitted under this framework.

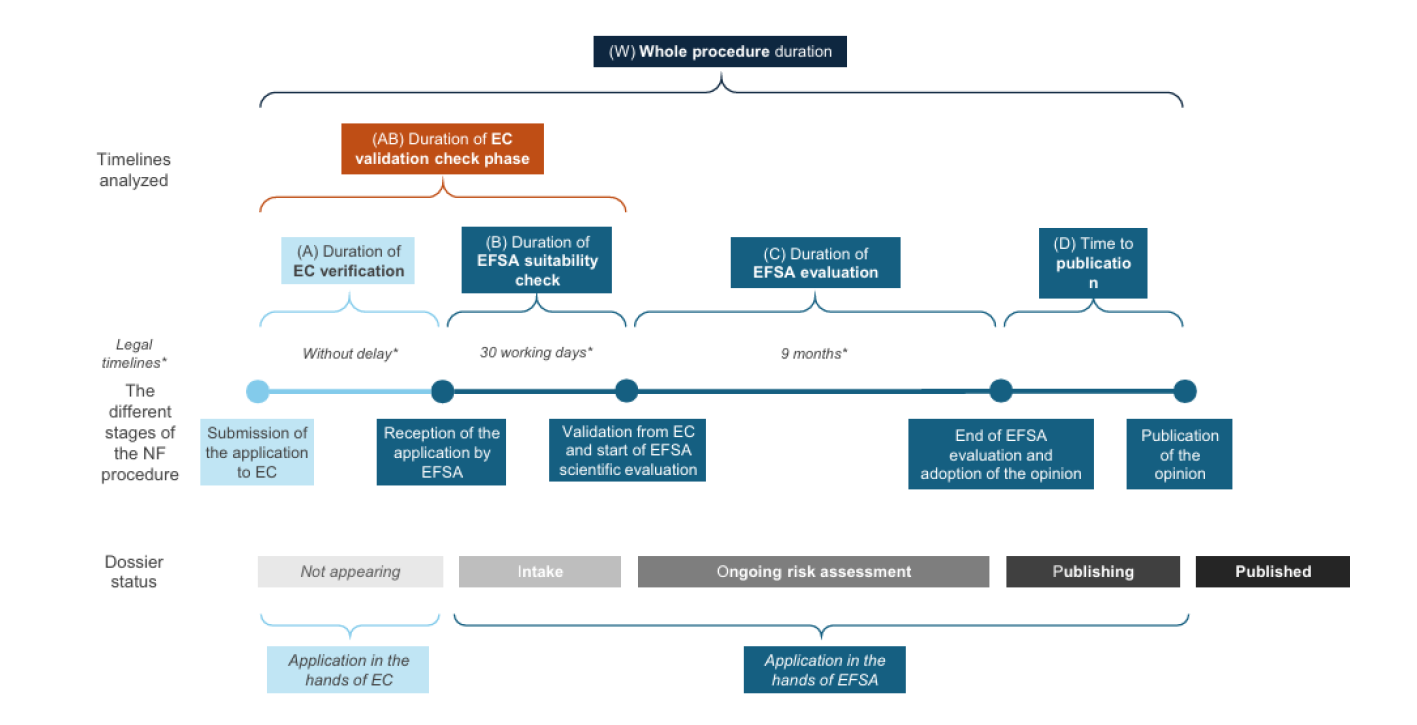

A recent analysis by Le Bloch (2025) offered the first comprehensive examination of processing timelines under Regulation (EU) 2015/2283, revealing procedural inefficiencies and administrative bottlenecks within the EU system (see whole procedure in Figure 1.). The process begins with the submission of a scientific dossier to the European Commission (EC). The Commission is responsible for verifying the validity of the application and may consult EFSA during this phase. EFSA then has 30 working days to provide an initial opinion on the validity of the submission, which is followed by the publication of a Scientific Opinion. Once the application is validated, the EC formally forwards it to EFSA, which then conducts the main risk assessment. EFSA’s role in this phase is to identify and characterize any potential hazards by comparing the novel food to similar products already on the market and assessing the associated risks under the proposed conditions of use. Although EFSA is expected to issue its opinion within nine months, this timeline is frequently extended due to requests for additional information from applicants. These delays have had a measurable impact on the overall process, with only 22 assessments completed in 2023, falling short of the targeted 42 evaluations. The final decision on whether to authorize a novel food does not rest with EFSA but with the political authorities. Based on EFSA’s scientific opinion, the Commission prepares a draft implementing act, which is then voted on by representatives of the Member States in the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed (PAFF). Once approved, the product is added to the Union List of Authorized Novel Foods and can be marketed across the EU. Importantly, each authorization is product-specific and not generalizable across categories.

The EU’s evaluation process is widely regarded as one of the most rigorous globally. Scientific requirements are detailed in EFSA’s guidance, which was recently updated and will come into force on 1 February 2025. This guidance includes comprehensive criteria relating to the production process, compositional data, toxicological assessments, allergenic potential, and the nature of additives and ingredients used during bioreactor cultivation. Two major regulatory developments have significantly shaped the current landscape. The first was the implementation of the Transparency Regulation in 2021, which revised scientific and technical guidance and introduced new obligations for food business operators. While enhancing transparency, this regulation has also extended and complicated the approval process. The second was the 2024 update to EFSA’s scientific guidance, reflecting accumulated experience and aiming to streamline future assessments.

Despite these procedural challenges, EFSA maintains a high rate of approval: 86.81% of opinions are ultimately positive. This indicates that, while demanding, the regulatory system is capable of supporting the safe introduction of novel foods into the EU market. By 2025, only a limited number of applications for the authorization of cultivated meat products had been submitted under the EU novel food framework, notably by Gourmey in 2024 and Mosa Meat in early 2025. This highlights both the novelty of the sector and the regulatory complexity companies must navigate to enter the European market.

United States

In the United States, the regulation of cultivated meat falls under the jurisdiction of multiple federal agencies. A formal regulatory framework was outlined in March 2019, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defined their respective roles in overseeing the production and commercialization of cultivated meat. Under this shared oversight model, the FDA is responsible for the early stages of production, including cell sourcing, development of cell banks, and tissue cultivation and maturation. Once the cultivated tissue is ready for harvest, jurisdiction shifts to USDA-FSIS, which oversees post-harvest activities such as processing, packaging, and labeling, in accordance with the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Poultry Products Inspection Act. This dual-agency approach applies to cultivated meat, poultry, and catfish, while products such as cultivated seafood fall solely under the FDA’s remit. Notably, there is currently no centralized regulatory regime for cultivated meat in the U.S., and each product is assessed individually. The regulatory emphasis, as stated in the formal agreement between USDA and FDA, remains focused on food safety and accurate labeling. Although the agencies have announced intentions to issue further guidance documents, regulatory uncertainty persists, particularly in light of increasing political attention to the sector. In recent years, several U.S. states, including Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Indiana and Texas, have introduced bans or restrictions on cultivated meat, adding another layer of complexity.

The regulatory process typically begins with a voluntary pre-market consultation with the FDA, during which the company provides a scientific rationale demonstrating the safety of its product. The FDA reviews the submission and produces a safety evaluation. However, there are currently no formal guidelines outlining how this consultation process should be conducted, and it remains unclear whether companies are pursuing regulatory approval via the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) route to avoid a more extensive pre-market review. Following the FDA’s safety evaluation, companies must secure USDA-FSIS approval for product labeling. This includes obtaining authorization for special statements and claims, although these are not yet clearly defined in federal regulations or policy. Before the product can be brought to market, the production facility must also receive a grant of inspection from USDA-FSIS. This step requires companies to demonstrate the implementation of robust Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures and to complete a hazard analysis supported by a validated HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) plan.

In 2023, the U.S. approved the fi rst cultivated meat products for sale, marking a significant milestone (UPSIDE Foods). Despite this progress at the federal level, state-level restrictions continue to pose challenges. Proponents of these bans argue that they may encourage further federal scrutiny or re-evaluation of regulatory procedures. Advocacy efforts in response to such bans have emphasized consumer rights and food freedom. A notable example was the world’s first public tasting of cultivated meat hosted by UPSIDE Foods in Miami, Florida, on June 27, 2024, framed as a celebration of the “Freedom of Food.”

Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand operate under a joint food regulation system governed by the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (ANZFSC), which is administered by the regulatory agency Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). Within this framework, cultivated meat products are generally regulated as novel foods, though depending on their characteristics and intended use, they may also fall under other categories such as food additives, processing aids, nutritive substances, or foods produced using gene technology. A novel food is defined as a non-traditional food that requires a public health and safety assessment. This assessment is triggered when the food raises potential safety concerns and is evaluated in light of its composition or structure, method of preparation, source material, consumption patterns, and other relevant factors. As such, cultivated meat meets the criteria for novel food status due to its lack of prior consumption history in the region.

Although FSANZ conducts the safety and technical assessment of applications, the final decision on whether to authorize a new food rests with the Australia and New Zealand Ministerial Forum on Food Regulation, a political body that makes rulings on standards and amendments proposed by FSANZ. This division of responsibility is comparable to the European system, where the regulator assesses safety, but elected representatives make the final determination. In recent regulatory developments, FSANZ proposed amendments to the ANZFSC that would require any food containing cell-cultured components to be explicitly permitted under the Code. If adopted, this change would effectively mean that cultivated meat products would require pre-market approval not solely because they are novel, but because they are cell-cultured. FSANZ also proposed two new standards specific to cultivated meat: (1) a general framework including labelling requirements and a schedule listing approved cultivated meat products and their conditions of use, and (2) production and processing requirements applicable to all cell-cultivated foods. These proposals indicate an intention to create a dedicated regulatory pathway for cultivated meat rather than relying entirely on the existing novel food framework. The development and implementation of these new standards is ongoing and subject to Ministerial approval. Their final form may evolve or be revised, and there is no certainty that all provisions will be enacted as currently proposed.

In evaluating novel foods and cultivated meat, FSANZ’s core objectives include the protection of public health and safety, the provision of adequate information to allow informed consumer choice, and the prevention of misleading conduct. In making regulatory decisions, FSANZ is also guided by broader policy goals: reliance on risk analysis and scientific evidence, alignment with international food standards, support for a competitive domestic food industry, promotion of fair trade, and adherence to relevant policy directives issued by the Ministerial Forum.

In June 2025, Australia approved its first cultivated meat product. The regulatory approval was granted to Vow Group Pty Ltd for a product derived from Japanese quail cells, marking a milestone in the implementation of FSANZ’s regulatory framework. This decision formalized the inclusion of the product in the Food Standards Code and demonstrated FSANZ’s ability to assess and authorize cultivated meat using its existing procedures. The product is expected to first enter the market through selected restaurants before broader commercial rollout.

Singapore

Singapore stands out as the only jurisdiction examined here that has developed dedicated guidelines specifically addressing the regulation of cultivated meat. The country’s regulatory framework is overseen by the Singapore Food Agency (SFA), which released its initial guidelines in 2019 under the title Requirements for the Safety Assessment of Novel Foods and Novel Food Ingredients. These were subsequently updated in 2023 to reflect evolving understanding and regulatory needs. The SFA guidelines provide a clear and structured outline of the general safety assessment requirements for novel foods, relying on data submitted by the applicant. Notably, the guidelines include specific provisions for the evaluation of cultivation media used in cultivated meat products, setting Singapore apart from most other jurisdictions, where such detailed regulatory direction is lacking.

In 2025, Singapore formalized its approach through the passage of the Food Safety and Security Act, which codifies that novel foods, including cultivated meat, cannot be produced, imported, distributed, or sold in the country without pre-market approval from the SFA. This legal framework reinforces the agency’s role in overseeing novel foods and ensures regulatory clarity and enforcement authority. As of November 2025, two cultivated meat products have been approved under this system: the first by GOOD Meat in 2020, and the second by Vow in 2024. Additional applications are currently under review, indicating that the regulatory pathway is both functional and active. Singapore’s regulatory approach does not operate in a vacuum but is heavily influenced by broader national objectives, particularly in relation to food security and technological leadership. The country has positioned itself as a pioneer in alternative proteins, using regulatory clarity and governmental support as tools to attract global innovators. This contrasts with other jurisdictions such as the EU, US, and Australia/New Zealand, where political and policy support for cultivated meat has been less pronounced or more fragmented. In Singapore, the regulation of cultivated meat is embedded in a wider strategy aimed at enhancing domestic production capacity and establishing the country as a global hub for novel food technologies.

Despite significant progress in selected jurisdictions, global regulatory frameworks for cultivated meat remain fragmented. Differences in approval procedures, legal definitions, and labeling requirements continue to pose major barriers to international commercialization. While the EU and Singapore have issued detailed scientific guidelines, other jurisdictions, including the US, Australia, and New Zealand, lack similarly specific documentation, leaving applicants to navigate less structured processes. One important point of divergence lies in public participation: Australia is currently the only jurisdiction requiring and incorporating public consultation in the approval of specific cultivated meat products. Moreover, while most jurisdictions share a common reliance on scientific risk assessments, the scope, depth, and formal expectations differ. For example, the EU regulatory system, widely regarded as the most rigorous, requires a higher level of scientific detail and procedural formality than systems such as that of Singapore, which is perceived as more flexible and innovation-oriented. That said, regulatory focus across all jurisdictions is converging around core technical concerns. These include the origin and stability of the cell lines, the composition of the cultivation medium (particularly the presence of growth factors, antibiotics, or residual components), and chemical and microbiological analyses ensuring product safety with regard to toxins, allergens, or contaminants. However, nuanced technical differences in application requirements and assessment processes, often apparent only to scientific experts, underscore the complexity of navigating approvals in different countries.

Looking ahead, emerging political developments add another layer of complexity. The introduction of bans on cultivated meat in several US states (Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Indiana and Texas), Italy’s December 2023 national ban on both production and sale of cultivated meat products signal rising tensions or latest Hungary ban. These actions also stand in contrast to statements made by European Commissioner Kyriakides in January 2024, reaffirming that the existing EU novel food framework is robust and fit for purpose. Her confidence was further supported by the publication of new dedicated EFSA guidance for cellular agriculture products in September 2024. Opponents of cultivated meat argue that the novel food framework does not account for socio-economic impacts, such as those related to European gastronomic heritage and traditional food culture. However, these concerns are already addressed through other regulatory mechanisms in the EU that protect high-quality regional foods and artisanal practices. From a legal standpoint, an outright national ban based on cultural or economic arguments is unlikely to withstand scrutiny under EU internal market law. Overall, pre-emptive bans and restrictive legislation, as seen in Italy and under consideration in France, Romania, and Poland, risk undermining the harmonized regulatory approach that the EU seeks to uphold. As the cultivated meat sector evolves, careful attention must be paid not only to scientific safety assessments, but also to the legal coherence and market compatibility of regulatory responses, balancing innovation, safety, and public trust in a rapidly changing food landscape.

Resources:

Gerber, S.; Bae, H.; Ramirez, I.; Cash, S. B. Publicly tasting cultivated meat and socially constructing perceived value politics and identity. Science of Food, 2025, 9, 94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00449-0

Johnson, H.; Monaco, A. Global developments in the regulation of cultivated meat: A comparative study of the EU, Singapore, US and Australia and New Zealand. RECIEL, 2025, 34, 2, 496‐511. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.70007

Khan, I.; Sun, J.; Liang, W.; Li, R.; Cheong, K.-L.; Qiu, Z.; Xia, Q. Innovations, Challenges, and Regulatory Pathways in Cultured Meat for a Sustainable Future. Foods, 2025, 14, 3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14183183

Monaco, A. A perspective on the regulation of cultivated meat in the European Union. Science of Food, 2025, 9, 21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00384-0

Le Bloch, J.; Roualt, M.; Langhi, C.; Hignard, M; Iriantsoa, V.; Michelet, O. The novel food evaluation process delays access to food innovation in the European Union. Science of Food, 2025, 9, 117. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00492-x