Cultivated meat aims to replicate not only the nutritional profile of conventional meat but also its organoleptic properties as flavor, aroma, juiciness, and texture. Achieving this complex sensory experience requires more than just growing the right cell types. It demands the recreation of the three-dimensional architecture that gives animal tissue its distinctive bite and structure. At the core of this challenge lies the development of scaffolding technologies, structures that support the organization, growth, and function of cells in vitro. Many of the current approaches to scaffolding originate from biomedical tissue engineering, where they have been designed to regenerate or replace damaged tissues. However, cultivated meat presents a very different set of constraints. While biomedical scaffolds are typically small, high-cost, and designed for implantation, scaffolds for cultivated meat must be scalable, affordable, food-safe, and compatible with high-throughput manufacturing. They must also contribute to the organoleptic qualities of the final product, enabling a fibrous, structured tissue that mimics the mouthfeel of traditional meat. A critical step in many cultivated meat bioprocesses, both current and theoretical, is the seeding of cells onto a three-dimensional scaffold. The scaffold is not simply a passive support. It actively shapes the cellular environment, enabling the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients, the removal of metabolic waste, and the spatial organization of cells into tissue-like formations. As the tissue grows in complexity and thickness, diffusion becomes insufficient on its own. Scaffolds help maintain cell viability by facilitating mass transfer and providing structural cues that guide tissue formation.

From a biological perspective, animal cells are evolutionarily adapted to function within a soft, gel-like matrix known as the extracellular matrix (ECM). This matrix not only provides mechanical support but also delivers biochemical and biophysical signals that regulate cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation. A well-designed scaffold can mimic this natural microenvironment, reproducing key aspects of ECM chemistry and mechanics to influence how cells behave. The interactions between cells and their surrounding matrix are essential for tissue morphogenesis and stability, making scaffold design a central concern in cultivated meat development.

Comparing two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) cell cultivation highlights the importance of scaffolds. In 2D cultivation, most of the cell membrane is either exposed to fluid or in contact with a rigid surface, resulting in artificial polarity and limited opportunities for cell–cell interaction. Adhesion molecules like integrins can only attach to the base of the cell, disrupting normal signal transmission. In contrast, 3D cultivations allow cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions across the entire surface of the membrane. This promotes more physiologically relevant behavior and supports the formation of complex tissue structures.

Scaffolds also help regulate mechanical stress within the cultivation environment. Flowing mediums in bioreactors can expose cells to shear forces that reduce viability. A well-designed scaffold, whether in the form of a porous solid or a soft gel, can buffer these forces, protecting cells from mechanical damage. In addition, scaffolds preserve concentration gradients that guide cell movement and organization. In static or poorly controlled systems, such gradients are often disrupted by media mixing, leading to unnatural cell behavior. By providing structural support, enhancing biological function, and buffering environmental stress, scaffolds play a pivotal role in the development of cultivated meat. They enable the growth of anchorage-dependent cells that require attachment to a surface, and open the door to microcarrier-based or scaffold-based suspension cultures suitable for industrial bioreactors. As such, scaffolding is not merely a technical consideration, it is one of the foundational tools that will determine whether cultivated meat can scale into a viable, affordable, and desirable food product.

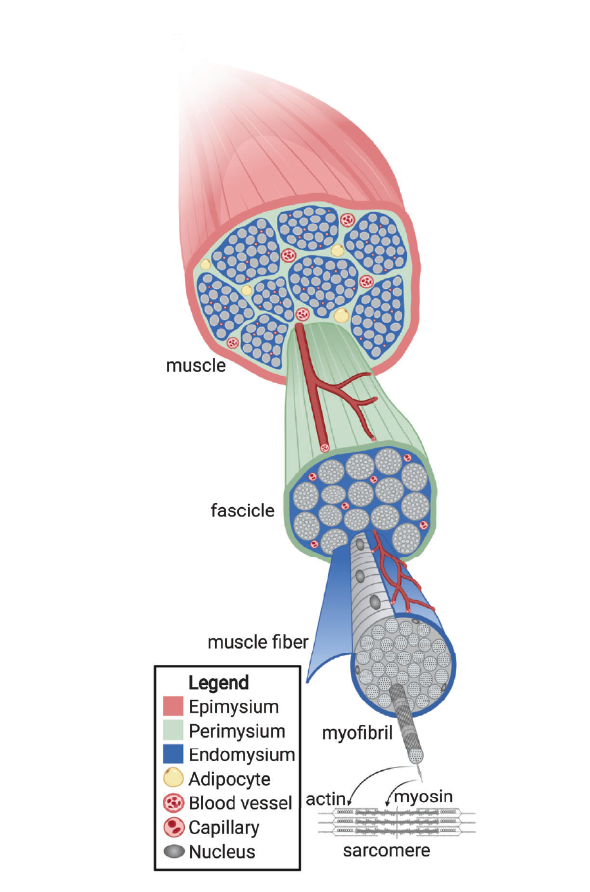

Structure of muscle tissue

In cultivated meat production, one of the key goals is to recreate a tissue structure that closely mirrors the composition and functionality of conventional meat. In most types of meat (no meat products) consumed by humans, whether beef, chicken, pork, or fish, this structure is predominantly composed of mature skeletal muscle fibers, accompanied by smaller amounts of intramuscular fat and connective tissue. Roughly speaking, muscle fibers account for about 90% of the tissue volume, while fat and connective tissue make up the remaining 10%. To achieve a realistic and desirable final product, cultivated meat manufacturers must understand and replicate this complex architecture. While vasculature is critical in vivo for the transport of oxygen, nutrients, and waste, it does not contribute significantly to the sensory properties of meat. Nevertheless, some functional analog to vasculature may be necessary in large cultivated tissues to ensure adequate nutrient exchange. Similarly, nerves are not required for the organoleptic qualities of meat, but their presence during cultivation may support muscle maturation, as electrical and biochemical cues from nerves influence muscle fiber development in vivo.

Skeletal muscle is one of three major muscle types found in vertebrates, alongside cardiac and smooth muscle. Unlike cardiac muscle, which powers the heart, and smooth muscle, which supports involuntary functions in organs such as the digestive tract or blood vessels, skeletal muscle is responsible for voluntary movement. From the perspective of cultivated meat, skeletal muscle is the primary target tissue. Fortunately, the structure and function of skeletal muscle are highly conserved across species, meaning that principles derived from one organism can often be applied to others. At the core of skeletal muscle is the muscle fiber (Figure 1., also called a muscle cell or myofiber), a long, cylindrical, multinucleated (with as many as 100 nuclei) cell that performs the contractile function of muscle tissue. Each fiber is packed with myofibrils, micrometer-scale bundles of actin and myosin filaments arranged into repeating units called sarcomeres. The regular, overlapping organization of these filaments creates the striated pattern visible under the microscope and is responsible for the contractile properties of muscle tissue. In red meat, these fibers contain higher levels of myoglobin, an iron-rich protein that stores oxygen within the cell. Myoglobin contributes to the red coloration of the tissue and provides a bioavailable source of heme iron, which is nutritionally important but also linked, in high intake, to increased health risks such as colorectal cancer. In contrast, white meat contains lower levels of myoglobin. Presence of myoglobin also reflects the metabolic specialization of the fibers: oxidative (slow-twitch) fibers, rich in myoglobin, support endurance activity and sustained contraction, whereas glycolytic (fast-twitch) fibers support rapid, powerful bursts of activity. In terrestrial animals, oxidative and glycolytic fibers are often intermixed throughout the muscle. In fish, however, the organization is more spatially distinct, with glycolytic fibers typically forming concentrated bands along the lateral flanks of the body. This structural variability among species is a factor to consider when designing scaffolds and cultivation strategies tailored to specific meat products.

Muscle fibers are not arranged randomly. Instead, they are grouped into organized bundles known as fascicles, which are surrounded and supported by layers of connective tissue. Three principal layers provide structural integrity and enable the transmission of mechanical forces: the endomysium surrounds individual muscle fibers, the perimysium encases bundles of fibers (fascicles), and the epimysium envelops the entire muscle. These connective tissue layers contribute directly to meat texture by influencing its elasticity, firmness, and chewiness. Notably, the endomysium forms a grid-like structure around individual fibers and acts as a scaffold for their alignment and maintenance. The perimysium plays a role in organizing intramuscular fat, integrating adipose cells into the tissue and supporting the development of marbling, which is a key contributor to flavor and juiciness.

Intramuscular fat plays a crucial role in shaping the sensory and nutritional qualities of meat. Embedded between muscle fibers and fascicles, adipocytes are the primary contributors to this fat fraction. Their presence is associated with increased juiciness, flavor intensity, and tenderness, attributes that define the eating experience. In addition to adipocytes, intramuscular fat includes structural lipids, phospholipids, and intracellular lipid droplets located within the muscle fibers themselves. The distribution and abundance of these lipid components are influenced by species, muscle type, breed, and nutritional status. Notably, adipocyte size also varies: salmon adipocytes typically measure under 50 ìm in diameter, while bovine adipocytes can exceed 100 ìm, reflecting substantial species-specific differences in lipid storage strategies.

Beyond fat, the extracellular matrix plays a central role in both cell biology and the mechanical properties of tissue. It is a complex, dynamic network of proteins and polysaccharides that is continuously remodeled through synthesis, degradation, and reorganization. In skeletal muscle, the ECM forms the dense connective tissue that surrounds and interconnects muscle fibers, shaping the architecture of the tissue and influencing how it responds to mechanical stress. The ECM is not a uniform structure but consists of three distinct layers (already mentioned above): endomysium, perimysium, and epimysium. Each layer differs slightly in its molecular composition and structural function. Interestingly, much of the load-bearing capacity of muscle tissue comes not from the muscle fibers themselves but from this collagenous network. This insight underscores the importance of recreating adequate support structures, whether through scaffolds or cell-secreted matrix components, in the cultivation of meat.

The ECM’s mechanical properties are also critical to the final texture of the product. Mimicking the stiffness, elasticity, and structural arrangement of native ECM is therefore essential. In cultivated meat systems, this can be achieved either by engineering scaffolds with comparable properties or by inducing cells to secrete their own ECM proteins during cultivation. Collagen is the primary structural protein in ECM, contributing significantly to the tensile strength of tissue. However, collagen-rich meat is considered less nutritious due to its high glycine content and the absence of essential amino acids such as tryptophan. This limitation is less relevant in commercial meat production, where animals are typically slaughtered at a young age, before extensive collagen cross-linking occurs. In fish, collagen is more heat-sensitive and contributes minimally to cooked texture, which is primarily determined by muscle fibers. As a result, fish muscle tends to flake upon cooking rather than firm up like terrestrial meat. In addition to collagen, ECM contains proteoglycans and glycoproteins that provide further structural integrity and biochemical signaling cues. These molecules support cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation, and may be instrumental in engineering tissues with desired properties in cultivated systems.

Scaffolding

In cultivated meat production, scaffolds are not merely passive structures, they serve multiple critical roles in supporting cell viability, guiding tissue architecture, and shaping the final product’s sensory qualities. As such, scaffolds must be carefully engineered to fulfill several biological and functional objectives, each contributing to the development of complex, structured tissues. The first essential function of any scaffold is to promote effective cell attachment. Animal cells are inherently anchorage-dependent, meaning they require a surface to adhere to in order to survive, proliferate, and differentiate. Some biomaterials naturally support cell adhesion due to the presence of bioactive motifs that resemble those found in the extracellular matrix. Examples include silk fibroin, gelatin, and textured vegetable proteins, which contain amino acid sequences that interact favorably with cellular integrins. Other materials, such as alginate or certain synthetic polymers, are biologically inert in their native form but can be modified, either chemically or through surface coatings, to enhance their adhesive properties. The choice of material and its surface characteristics directly influence the efficiency of cell seeding, distribution, and the overall success of the cultivation process.

A second key role of scaffolds is to promote the maturation and alignment of muscle cells. In vivo, muscle fibers are highly ordered and aligned in parallel bundles, a structural feature that contributes to the distinct textural properties of meat. This alignment not only enhances mechanical properties but also supports proper muscle cell differentiation, gene expression, and protein synthesis. Fully matured muscle fibers contain high levels of actin, myosin, and myoglobin. Without aligned scaffolds, cells tend to grow in disorganized patterns, leading to tissue structures that lack the integrity and organoleptic appeal of conventional meat.

A third challenge addressed by scaffold design is the creation of vascular-like structures within the tissue. In natural muscle, blood vessels are responsible for delivering oxygen and nutrients to every cell and for removing metabolic waste. In the absence of such a network, diffusion becomes the limiting factor, restricting viable tissue thickness to just a few hundred microns. Only tissues with low metabolic demands, such as cartilage or cornea, can survive without vascularization. For cultivated meat, which aims to replicate dense, metabolically active tissues like muscle, the development of perfusable or vascular-mimicking networks is essential.

Scaffolding materials

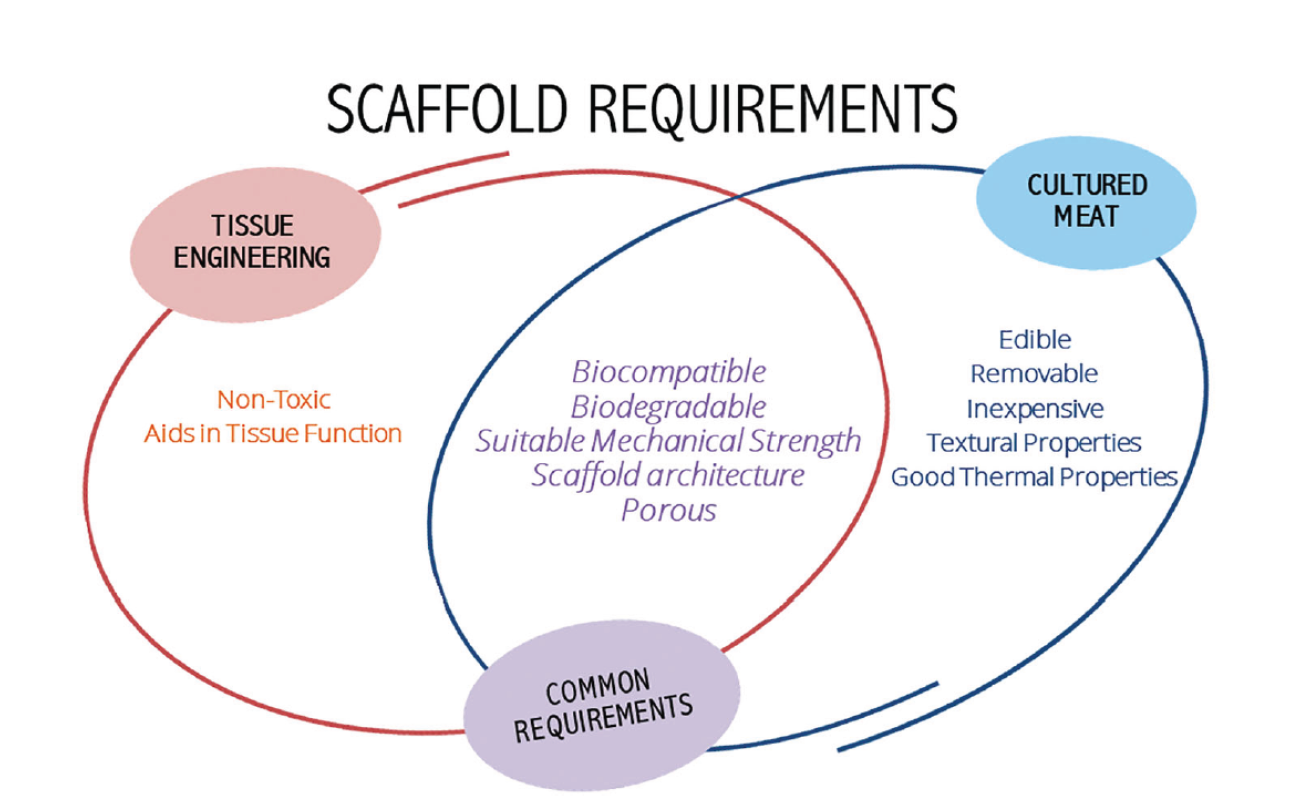

The choice of scaffold material has a profound influence on the structural and functional outcomes of cultivated meat. Scaffolds must provide an environment that not only supports cell adhesion and viability, but also guides cellular organization, differentiation, and tissue maturation. The ideal biomaterial should possess excellent biocompatibility, high porosity, and sufficient mechanical strength, while mimicking the architecture and cues of the extracellular matrix. In the context of cultivated meat, however, scaffold materials must meet a unique set of criteria beyond those required for biomedical applications. They must be edible, safe for human consumption, and suitable for large-scale, cost-effective production. Beyond edibility and scalability, additional considerations include sustainability, biodegradability, and the absence of non-edible or toxic compounds such as chemical crosslinkers or organic solvents. These requirements impose strict limitations on the pool of usable materials, particularly when aiming to comply with food-grade standards and ethical expectations. Naturally occurring ECM is composed primarily of structural proteins and complex polysaccharides, most notably proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and various types of collagen. Consequently, scaffold biomaterials for cultivated meat are most commonly derived from proteins and polysaccharides.

Animal-derived biomaterials are already part of conventional meat and therefore inherently edible, which makes them a logical candidate for use in cultivated meat scaffolding. These materials include a variety of biomacromolecules such as polysaccharides (e.g., chitosan), proteins (collagen, gelatin, fibrin), and polynucleotides. Their natural richness in ECM components promotes favorable conditions for cellular growth and tissue development, supporting full cellular integration and bioabsorption. Notably, key ECM components such as elastin, collagen, gelatin, fibronectin, hyaluronic acid, and chitosan (traditionally derived from shellfish but also obtainable from mushrooms) have demonstrated potential to guide cell behavior and tissue structuring effectively. Because animal-derived ECM closely resembles the texture and architecture of traditional meat, it may offer a more authentic sensory profile in the final product. Among these, collagen and gelatin are the most widely studied due to their well-established biocompatibility, biodegradability, and minimal immunogenicity, as evidenced by their widespread use in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. For instance, the incorporation of smooth muscle cells into a collagen gel-based scaffold model has been shown to reduce pressure loss, enhance collagen accumulation, and improve mechanical features such as springiness and firmness, important characteristics for the textural perception of meat. However, the use of animal-derived scaffolds in cultivated meat production poses several challenges. It undermines one of the primary motivations for cultivated meat, namely, the ethical and environmental benefits of reducing animal agriculture. These materials also tend to be more expensive and less reproducible than synthetic or plant-based alternatives due to natural variability in animal tissues. Finally, ensuring food safety and avoiding contamination with pathogens remain critical hurdles when working with animal-sourced components. Some non-traditional sources have also emerged. Edible insects are rich in structural proteins like collagen and chitin, and while less conventional, they could be explored as scaffold material. Moreover, collagen and gelatin can be engineered via microbial fermentation using yeast or bacteria, and fibers derived from edible fungi (such as enoki mushroom polysaccharides) are being investigated for their functional roles in supporting cell attachment and proliferation.

Plant-derived scaffolding materials, such as polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, starch, glucomannan) and proteins (e.g., soy, pea, and zein), are considered highly promising for cultivated meat applications. Their nutritional value, affordability, consumer acceptance, and inherent biocompatibility make them a prime choice, especially for producers aiming for a fully animal-free process. Although these materials often exhibit weak mechanical properties, they are biodegradable and less likely to trigger immunogenic responses. Their compatibility with cells and sustainability profile outweigh many of their structural limitations, which can be addressed through various modification techniques. Plant proteins have shown promise in promoting cell adhesion and growth. For instance, soy protein isolate has demonstrated good attachment capabilities for muscle cells, while scaffolds made from peanut-derived proteins have also supported cell viability. Zein, a storage protein from corn, and cellulose have both emerged as promising candidates due to their structural adaptability and surface compatibility. Decellularized plant tissues such as spinach leaves, celery stalks, and apple slices have attracted attention for their natural vascular-like structures and porosity, which can facilitate oxygen and nutrient transport, two critical parameters in thick tissue constructs. Even more structurally rigid plant parts, like jackfruit rind and corn husk, have been successfully decellularized and used as scaffolds, providing adequate support for bovine satellite and avian cells. Despite their advantages, plant-derived materials generally require reinforcement to meet the mechanical demands of meat-like textures. To this end, edible or food-safe crosslinking agents such as citric acid, sodium hydroxide, sodium phosphates, or transglutaminase (a common food enzyme) are often employed to improve structural stability. These crosslinking techniques enhance the physical integrity of plant-based scaffolds while maintaining regulatory compliance and consumer safety.

Algae have also emerged as a promising source of scaffold materials due to their abundance, sustainability, and nutritional benefits. Widely consumed as food in many cultures, algae are generally considered safe and contain a wide range of bioactive compounds, including polysaccharides, proteins, bioactive peptides, essential fatty acids, and vitamins. These properties make them attractive candidates for use in cultivated meat scaffolds. Among algae-derived polysaccharides, carrageenan, alginate, and agarose are the most extensively explored. These materials can support cell encapsulation and three-dimensional growth, but they often require combination with other biopolymers to enhance mechanical strength, cell adhesion, and structural integrity. Alone, they may lack the optimal viscoelastic and adhesive properties needed for complex tissue formation. Macroalgae (seaweeds) are generally considered more suitable for edible scaffold development than microalgae, primarily due to their lower pigmentation and more neutral taste profiles. In contrast, microalgae can present challenges in scaffold design. Their strong pigmentation, aquatic odor, and high moisture content can negatively affect the texture, flavor, and sensory experience of the final cultivated meat product, making them less favorable as primary scaffold materials for consumption.

Microbial-derived biomaterials are produced through microbial fermentation involving various genera of bacteria, yeast, and molds. These materials have gained increasing attention due to their biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity, making them attractive candidates for cultivated meat scaffolds. However, despite these advantages, they often come with limitations such as low nutritional value and a lack of native cell-binding sites, which may reduce their effectiveness in supporting robust cell adhesion and tissue development without further modification. One of the most studied materials in this category is bacterial cellulose, which is known for its high purity, strength, and water-holding capacity. It provides a highly porous and fibrous structure, ideal for cell infiltration and nutrient diffusion. However, because it lacks specific biochemical signals for cell adhesion, it is often combined with proteins or modified chemically to improve its biological functionality. Another example is gellan, which forms stable gels even at low concentrations.

Synthetic polymers are originally developed for tissue or pharmaceutical engineering. They have also found utility in the cultivated meat field, particularly in the form of microcarriers or other porous and fibrous structures. These materials offer high tunability, reliable mechanical strength, and controlled biocompatibility. Common examples include polyvinyl alcohol, polypropylene, polycaprolactone, and polylactic acid. A significant advantage of synthetic polymers is their batch-to-batch reproducibility, ensuring consistent performance across production cycles. However, many synthetic polymers are non-edible or only partially degradable, posing limitations when applied to food-grade applications. Despite this, certain synthetic polymers have shown promising potential in cultivated meat scaffolding due to their ability to support vascularization and tissue formation. Polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid, and their copolymer are the most commonly used in tissue engineering, with proven efficacy in supporting the growth of various cell types. Hydrogels based on polyethylene glycol have been shown to support multi-layered skeletal myoblast cell growth, especially when engineered with internal channels that enhance nutrient and oxygen diffusion.

Self-assembling peptides (SAPs) represent a promising category of scaffold materials due to their versatility and ability to mimic the ECM. These peptides are composed of monomers that spontaneously organize into well-defined structures in response to environmental stimuli, making them suitable for a wide range of applications. By adjusting the peptide sequences, SAPs can be tailored to meet specific structural and functional requirements. The side chains of amino acids within these peptides provide functional sites for chemical modifications, enabling the creation of diverse supramolecular structures and hydrogels. These hydrogels can be engineered to possess valuable characteristics such as shear-thinning, bioactivity, self-healing, and shape memory. Such features expand the scope of SAPs as dynamic and adaptable materials for scaffolding in cultivated meat production. Notably, SAPs like CH-01 and CH-02 have been used to generate hydrogels with nanofibrous architectures that closely resemble the collagen-rich ECM found in natural meat. These scaffolds successfully support cellular adhesion and growth, while mimicking the fibrous texture essential for recreating realistic meat structures. Despite their potential, the application of SAPs in cultivated meat remains largely unexplored. A major limiting factor is the high cost associated with conventional peptide synthesis, which presents a barrier to broader adoption and further research into their scalability and affordability.

Scaffolding for cultivated meat

Over the past several years, significant advances in biofabrication technologies have revolutionized the field of three-dimensional scaffold engineering. A wide array of strategies has emerged, each offering distinct advantages in terms of cellular compatibility, nutrient transport, mechanical properties, and scalability. Scaffold systems can now be tailored with high precision to meet the specific demands of cultivated meat production, from small-scale prototyping to industrial manufacturing (see scaffold requirements in Figure 2.). Scaffold architectures can take on a diverse range of forms, broadly categorized based on their structure and material behavior. Among the simplest and most scalable platforms are microcarriers: small, spherical particles that serve as substrates for cell growth in suspension cultivation. Beyond microcarriers, most three-dimensional scaffolds fall into one of three primary categories: porous scaffolds, hydrogels, and fibrous scaffolds. Although these classes may overlap in function, they differ substantially in their structural architecture and performance characteristics. A rapidly evolving frontier in scaffold engineering is three-dimensional bioprinting, which enables the layer-by-layer deposition of bioinks, composites of cells, biomaterials, and growth factors, into precisely defined architectures. This technology allows for the fabrication of complex, multi-tissue constructs with high spatial resolution, opening new possibilities for mimicking the hierarchical organization of natural meat. By printing different cell types into designated regions and incorporating vascular-mimetic channels, 3D bioprinting holds the potential to produce thick, heterogeneous meat analogs with unprecedented fidelity. However, challenges such as limited print speed, material constraints, and regulatory uncertainty must be addressed before this technology can be scaled for commercial production.

The concept of growing adherent cells on small particles, microcarriers, in suspension was first introduced by van Wezel in 1967, laying the foundation for what would become a widely adopted platform in large-scale cell cultivation. Since then, a variety of commercial microcarrier products have been developed, primarily targeting the pharmaceutical and biomedical sectors. These platforms have proven highly effective for mass expansion of functional living cells, including human mesenchymal stem cells, embryonic stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells. Their use is well established in vaccine production and cell therapy manufacturing. Microcarriers are typically small, spherical beads with diameters ranging from 100 to 200 ìm, providing a sufficient surface area for cell attachment while remaining suspended in dynamic cultivation environments. They enable efficient encapsulation of cells and help reduce cell necrosis, which is a common challenge in high-density cultivation. Microcarriers can be fabricated from synthetic or natural polymers, with common materials including polystyrene, cross-linked dextran, cellulose, gelatin, or polygalacturonic acid. To enhance adhesion, their surfaces are often coated with collagen, adhesive peptides, or functionalized with positive charges.

Microcarriers differ in size, porosity, rigidity, density, and surface chemistry, all of which influence their performance in specific applications. In cultivated meat production, microcarriers are used in several distinct ways: 1. As temporary carriers for cell proliferation, after which the cells are removed and further processed. 2. As biodegradable or dissolvable carriers, which release the cells during or after cultivation. 3. As edible carriers, which are incorporated directly into the final product. One of the key advantages of microcarriers lies in the ease of producing large material volumes and their compatibility with various types of bioreactors, supporting the efficient proliferation of anchorage-dependent cells. However, challenges remain, particularly concerning cost, potential inedibility, and limitations in cell harvesting efficiency. Studies have demonstrated that microcarrier surfaces can be quickly and completely covered with cells, allowing for rapid proliferation within a few days. However, incomplete detachment of cells from microcarriers can result in cell loss and reduced production efficiency, which presents a trade-off in large-scale operations. Thus, while microcarriers offer a relatively simple and space-efficient solution for scaling mammalian cell cultures, they may also introduce technical and economic constraints, including costs related to cell separation, limitations in maximum achievable cell densities, and potential effects on the nutritional or sensory properties of the final cultivated meat product. Experimental research continues to refine microcarrier technologies. A 3D porous microcarrier made from gelatin (PoGelat-MC) has been utilized as an expansion scaffold to support the growth of pig skeletal muscle cells, mouse muscle cells, and mouse adipose cells. In a separate study, Yen et al. (2023) developed edible microcarriers in combination with an oleogel-based fat substitute, while other experiments have demonstrated the successful cultivation of bovine mesenchymal stem cells on edible chitosan–collagen microcarriers, resulting in the formation of cellularized microtissues.

Porous scaffolds possess a sponge-like internal architecture that provides the mechanical stability required for seeded cells to attach, grow, and begin forming functional tissue. Their structure plays a pivotal role in facilitating the deposition of ECM and promoting tissue regeneration, while also enabling the delivery of bioactive compounds during the cultivation process. A key advantage of porous scaffolds lies in their interconnected pore networks, which allow for the efficient transport of nutrients and oxygen throughout the construct. This porosity ensures that cells are provided with an optimal microenvironment to adhere, spread, and differentiate, which is essential for building viable, thick tissues. To fully support muscle tissue formation, porous scaffolds should ideally recapitulate the architecture, mechanical properties, and composition of the perimysium, the connective tissue layer that surrounds muscle fascicles and plays a critical role in structural integrity and alignment. Critical parameters such as pore size, nutritional value, texture, and elasticity directly impact tissue development and cell viability.

Optimizing these features is essential for improving scaffold performance in cultivated meat applications. While some porous scaffolds are still fabricated from synthetic polymers, there is increasing pressure to replace these with edible alternatives suitable for food applications. Among promising materials for porous scaffolds in cultivated meat applications is textured vegetable protein (TVP). Produced by moisture extrusion from plant-based sources (most commonly soy protein powder, often obtained as a sidestream product of the oil industry), TVP represents a highly scalable and cost-effective biomaterial. Other plant-derived proteins, such as peanut protein, gluten, soy flour, and soy protein concentrate, have also been investigated as feedstocks for extrusion-based porous scaffolds. These materials provide edibility, affordability, and biocompatibility, and their properties can be adjusted during manufacturing to tailor pore structure and mechanical behavior. For example, Xiang et al. (2022) developed a 3D porous scaffold from whey glutenin that contained no toxic components, remained structurally stable during cultivation, and effectively supported the growth of C2C12 mouse myoblasts and bovine satellite cells. Another example comes from Chen et al. (2023), who created a porous scaffold by crosslinking gellan gum and gelatin with Ca². ions.

This approach resulted in materials that mimicked both the texture and color of genuine meat products, demonstrating their potential for cultivated meat fabrication. While advanced fabrication techniques developed in regenerative medicine offer tools to enhance the architectural resolution of porous scaffolds, their use in cultivated meat remains constrained by cost and scalability limitations. Nevertheless, the continued refinement of porous plant-based and edible scaffolds is likely to play a central role in the development of structured cultivated meat products with desirable organoleptic and nutritional profiles.

Fiber scaffolds are characterized by their highly organized, fibrillar architecture that can be engineered to closely mimic the alignment and anisotropy of native skeletal muscle. These structures are often fabricated using spinning techniques, most notably electrospinning and rotary jet spinning, which allow for the generation of nanofibers with high precision and tunable orientation. The nanoscale architecture of fiber scaffolds offers several critical advantages for cultivated meat applications. Cells can attach directly to the individual fibrils of the scaffold, and the aligned fiber geometry can help induce cellular alignment, a key requirement for successful myogenesis. The high specific surface area of nanofiber scaffolds provides numerous attachment points for cells and facilitates precise structural remodeling, both of which enhance cell adhesion and proliferation.

While cells adhere to the fibers themselves, the spaces between fibers permit the diffusion of oxygen, nutrients, and signaling molecules, allowing for healthy tissue development even in thicker constructs. Furthermore, the ability to produce aligned fibers gives fiber scaffolds a unique advantage in promoting muscle fiber maturation, helping to recreate the ordered structure of skeletal muscle tissue. Despite their potential in food applications, most existing investigations into fiber scaffolds have originated in the biomedical field, with a large proportion of patents and research focused on synthetic polymers designed for regenerative medicine or tissue repair. These materials are not typically edible and may not meet food safety requirements, limiting their applicability in cultivated meat production. In contrast, a number of edible materials have been identified as promising candidates for food-grade fiber scaffolds. These include collagen, gelatin, whey protein, chitosan, cellulose, and starch. These materials can be processed into nanofibrous forms while maintaining compatibility with mammalian cells and aligning with the regulatory expectations for human consumption. An illustrative example is the work of MacQueen et al. (2019), who demonstrated the growth of rabbit myoblasts and bovine smooth muscle cells on rotary jet-spun gelatin derived from pig tissue, using transglutaminase and a chemical crosslinking agent (EDC/NHS) to stabilize the scaffold.

This approach showed promising results in supporting muscle cell growth while maintaining the mechanical integrity of the scaffold structure. Recent research has also explored natural sources of fibrous scaffolding, such as mycelial mats from various fungal species or fibrous architectures derived from algae. These materials offer potential advantages in terms of sustainability, biodegradability, and edibility, and may expand the portfolio of scaffold materials suitable for cultivated meat applications as the field continues to mature.

Hydrogels are three-dimensional, hydrophilic polymer matrices characterized by their high water-holding capacity. They are stabilized through either physical or chemical crosslinking, forming a soft yet cohesive network capable of interacting with living cells. In the context of cultivated meat, hydrogels are considered a rational biomaterial choice due to their ability to mimic the ECM and provide a supportive microenvironment for cell behavior and tissue development. Their key advantages include high water content, tunable mechanical properties, and excellent biocompatibility. These attributes make them suitable not only for encapsulating cells but also for supporting cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation. To be effective in cultivated meat production, hydrogels must fulfill several vital requirements. They must be cytocompatible, composed of materials that are non-toxic to cells, and designed to allow adequate diffusion kinetics. The movement of nutrients, oxygen, and signaling molecules through the hydrogel depends heavily on its crosslinking density and microporous architecture.

These properties must be optimized to ensure that diffusible factors can penetrate the entire volume of the hydrogel at rates sufficient to support embedded cells. Moreover, the stiffness of the hydrogel plays a significant role in influencing cell motility, proliferation, and differentiation. For optimal outcomes, cells should be able to remodel or degrade the hydrogel over time, replacing it with their own ECM components as tissue formation progresses.

To enable such dynamic interactions, adhesion motifs and proteolytic cleavage sites should be incorporated directly into the hydrogel matrix. Further refinement can be achieved by integrating molecules such as heparan sulfate, which bind growth factors and enhance biochemical signaling. These additions help replicate the complex, signal-rich environment of native tissues. Hydrogels are versatile tools within cultivated meat systems. They may be used on their own as ECM-like 3D environments, as matrix fillers embedded within porous scaffolds, as source materials for developing porous architectures, or as components of bioinks in 3D bioprinting applications. In tissue engineering, synthetic hydrogels are commonly utilized due to their inert biological properties, which help prevent unwanted immune responses. A well-known example is polyethylene glycol, often used in biomedical contexts. However, for food applications, food-grade hydrogels are preferred. One such example is carrageenan, a hydrogel derived from edible seaweed species, which has been shown to be suitable for tissue engineering purposes while also complying with safety and regulatory standards for human consumption.

Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting is a fabrication technique that enables the layer-by-layer deposition of functional materials according to computer-generated 3D model data.

This approach allows for the self-assembly of biologically relevant structures, offering the ability to replicate tissue-like architectures with increasing precision. In cultivated meat applications, 3D bioprinting enables cells to be placed in predefined spatial patterns, using bioinks that are designed to exhibit specific mechanical and biological properties. The printing process not only controls cell positioning but also influences tissue organization, enabling the formation of more physiologically accurate constructs. For food applications, however, the requirements for bioinks are more stringent. Bioinks used in cultivated meat production must be either edible or capable of fully degrading during the cultivation process into non-toxic, food-safe components. This is a key distinction from biomedical applications, where biocompatibility is essential but edibility is not.

Although 3D bioprinting has been demonstrated for a wide range of materials, most of the bioinks relevant to cultivated meat are hydrogel-based. Examples of food-compatible formulations include whey protein and gellan gum blends, as well as combinations of collagen or gelatin with hyaluronic acid. These materials can provide the necessary viscoelasticity for printing while maintaining cell viability and support for tissue growth. One of the distinct advantages of 3D bioprinting in cultivated meat is its capacity to promote myotube alignment (a critical aspect of muscle tissue maturation) and to facilitate the creation of vascular-like channels within the printed structure. These channels improve the diffusion of nutrients and oxygen, enabling the development of thicker and more complex tissues. In a recent demonstration, bovine satellite cells were successfully used to simulate muscle growth on a multi-layered fiber network scaffold. The scaffold was composed of a combination of pea protein isolate, soy protein isolate, and seaweed salts, printed into a gelatin support bath. This system not only supported the alignment and proliferation of muscle cells but also enabled the development of constructs with thickness and organization approaching that of natural meat.

Decellularized scaffolds have emerged as a promising and widely investigated platform for supporting the proliferation and differentiation of myogenic cells, primarily due to their remarkable compatibility with the physiological conditions found in natural tissue environments. By preserving the native ECM architecture while removing all cellular components, these scaffolds create a biologically faithful microenvironment that fosters optimal conditions for tissue development. One of the key advantages of decellularized materials is their ability to mimic the native cellular environment, making them an optimal substrate for the cultivation and maturation of muscle and other relevant cell types. Their inherent biocompatibility and bioactivity support robust cell attachment and signaling, often without the need for additional modification. Moreover, decellularized scaffolds can be derived from renewable biological sources, offering a sustainable pathway for producing cultivated meat scaffolds. Beyond structural and functional relevance, these materials may also enhance the nutritional profile of the final product, depending on their composition and origin. In this way, they offer the dual benefit of enabling tissue formation while contributing to the sensory and dietary qualities of the cultivated meat.

A particularly innovative example of this approach was demonstrated by Jones et al. (2021), who successfully decellularized spinach leaves to produce an edible scaffold featuring a natural vascular network. The leaf vasculature, once cleared of plant cells, provided a pre-existing channel system capable of facilitating nutrient and oxygen transport. Despite their potential, scalability remains a critical limitation for decellularized scaffolds. Current bioreactor designs are not yet optimized to process large volumes of plant- or animal-derived tissues for decellularization at industrial scale. As such, while these materials are attractive for prototyping and high-fidelity tissue modeling, their application in large-scale cultivated meat production is still constrained by technological and logistical challenges.

Scaffold-free tissue engineering offers an alternative strategy for cultivated meat production by eliminating the need for conventional support structures. These systems rely entirely on cell–cell interactions and endogenous ECM to form three-dimensional tissues. By removing exogenous materials from the process, scaffold-free approaches can address some of the key challenges in nutrient and oxygen transport while avoiding complications related to scaffold biocompatibility, edibility, or degradation. One of the most explored techniques in this category is cell sheet stacking, where layers of adherent cells are cultivated and assembled into thicker constructs. The resulting tissues are held together by the cells’ own secreted ECM, creating material-free three-dimensional structures. Among scaffold-free methods, this strategy is notable for its ability to produce tissues without foreign biomaterials while preserving high cell density and contact. A prominent example is the ð-SACS method, which uses pH changes to detach intact cell layers, allowing them to be folded into larger, multi-layered structures. This approach has been successfully applied to generate C2C12 muscle tissues several millimeters in diameter and up to four layers thick. It has also been adapted to combine muscle and adipose cells, contributing to more complex tissue models. However, these methods require extensive 2D cultivating space to expand enough cells for layering, as well as manual manipulation, which presents a barrier to industrial adoption.

Potential solutions include the development of new bioreactor geometries and automation systems that could streamline production. Another promising scaffold-free concept is based on organoids and self-assembling cell clusters, which can be fused into larger functional units, often referred to as assembloids. These can combine multiple tissue types (such as muscle, fat, ligament, and vascular elements) into composite constructs. Because they are harvested before necrosis develops, they typically do not require long-term perfusion or vascularization, distinguishing them from scaffold-free systems used in transplantation medicine. A notable demonstration of scaffold-free cultivated meat comes from Tanaka et al. (2022), who produced cell-based meat constructs from stacked bovine myoblast sheets. The engineered tissue reached 1.3 to 2.7 mm in thickness, with textural properties resembling natural meat. However, the protein content was approximately half that of beef, and the final product contained a higher proportion of carbohydrates. This reflects a known challenge in scaffold-free systems: limited control over final tissue architecture, which can affect both composition and mechanical performance. Nevertheless, other studies have reported scaffold-free constructs with higher protein yields, highlighting the influence of cell type, cultivation conditions, and construct design.

While scaffold-free approaches offer unique advantages in terms of biocompatibility, material simplicity, and regulatory alignment, they also come with technical constraints that must be addressed to enable scalable, reproducible, and nutritionally optimized cultivated meat products. A broad spectrum of approaches has been explored for recreating the structure and functionality of muscle tissue in cultivated meat. These range from scaffold-based strategies, employing a wide variety of biomaterials and fabrication techniques, to scaffold-free methods such as organoids and cell sheets, which rely entirely on cell self-organization and endogenous matrix production. Despite this diversity, identifying the ideal scaffolding material remains a key challenge. Materials must be biocompatible, non-toxic, and capable of supporting cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. At the same time, they need to replicate the structure, texture, and mechanical behavior of conventional meat, which places significant demands on both biological and physical properties.

However, many materials continue to struggle with mechanical stability, nutrient diffusion, or supporting consistent cell maturation, particularly when applied to larger-scale constructs. In addition, the transition from laboratory-scale prototypes to mass production requires that scaffolds also be edible, cost-effective, and scalable, further narrowing the field of viable candidates. Encouragingly, recent research has demonstrated progress in cultivating muscle tissues with thicknesses ranging from several millimeters to centimeters, including early prototypes that begin to resemble structured or whole-cut products. Nonetheless, the first cultivated meat products reaching the market are likely to remain unstructured formats (such as burgers or sausages) which bypass the need for hierarchical tissue organization. To move beyond these formats, future efforts must focus on enabling oxygen and nutrient transport in a simple, scalable, and cost-effective manner. Here, hybrid strategies appear particularly promising. For example, combining hydrogels with 3D bioprinting can create spatially controlled, cell-compatible environments that support both tissue morphogenesis and structural complexity. Such multimodal approaches may offer the most viable path forward in engineering large, organized, and physiologically relevant meat analogs.

Resources:

Bomkamp, C.; Skaalure, S. C.; Fernando, G. F.; Ben-Arye, T.; Swartz, E. W.; Specht, E. A. Scaffolding Biomaterials for 3D Cultivated Meat: Prospects and Challenges. Advanced Science, 2022, 9, 2102908. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202102908

Fasciano, S.; Wheba, A.; Ddamulira, Ch.; Wang, S. Recent Advances in Scaffolding Biomaterials for Cultivated Meat. Biomaterials Advances, 2024, 162, 213897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioadv.2024.213897

Gu, H.; Kong, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y.; Raghavan, V.; Wang, J. Scaling Cultured Meat: Challenges and Solutions for Affordable Mass Production. Comprehensive Review in Food Science and Food Safety, 2025, 24, 4, e70221. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.70221

Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Shao, W.; Chen, X.; Fan, X.; Liu, Y.; Ding, S.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Gellan gum-gelatin scaffolds with Ca2+ crosslinking for constructing a structured cell cultured meat model. Biomaterials, 2023, 299, 122176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122176

Jones, J. D.; Rebello, A. S.; Gaudette, G. R. Decellularized spinach: An edible scaffold for laboratory-grown meat Growing meat on spinach. Food Bioscience, 2021, 41, 2-3, 100986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2021.100986

Lee, D.-K.; Kim, M.; Jeong, J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Yoon, J. W.; An, M.-J.; Jung, H. Y.; Kim, Ch. H.; Ahn, Y.; Choi, K.-H.; Jo, Ch.; Lee, Ch.-K. Unlocking the potential of stem cells: Their crucial role in the production of cultivated meat. Current Research in Food Science, 2023, 7, 100551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100551

MacQueen, L. A.; Alver, C. G.; Chante, C. O.; Ahn, S.; Cera, L.; Gonzales, G. M.; O’Connor, B. B.; Drennan, D. J.; Peters, M. M.; Motta, S. E.; Zimmerman, J. F.; Parker, K. K. Muscle tissue engineering in fibrous gelatin: implications for meat analogs. Science of Food, 2019, 3, 20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-019-0054-8

Park, S.-M.; Ryoo, J.-H.; Kwon, H. Ch.; Han, S. G. Scaffold Biomaterials in the Development of Cultured Meat: A Review. Food Science of Animal Resources, 2025, 45, 3, 688-710. https://doi.org/10.5851/kosfa.2025.e13

Piantino, M.; Muller, Q.; Nakadozono, Ch.; Yamada, A.; Matsusaki, M. Towards more realistic cultivated meat by rethinking bioengineering approaches. Trends in Biotechnology, 2025, 43, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2024.08.008

Santos, A. C. A.; Camarena, D. E. M.; Reigado, G. R.; Chambergo, F. S.; Numes, V. A.; Trindade, M. A.; Maria-Engler, S. S. Tissue Engineering Challenges for Cultivated Meat to Meet the Real Demand of a Global Market. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24, 6033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076033

Seah, J. S. H.; Singh, S.; Tan, L. P.; Choudhury, D. Scaffolds for the manufacture of cultured meat. Critical reviews in Biotechnology, 2022, 42, 2, 311-323. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2021.1931803

Tanaka, R.-i.; Sakaguchi, K.; Yoshida, A.; Takahashi, H.; Haraguchi, Y.; Shimizu, T. Production of scaffold-free cell-based meat using cell sheet technology. Science of Food, 2022, 6, 41. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-022-00155-1

Wang, Y.; Zou, L.; Liu, W.; Chen, X. An Overview of Recent Progress in Engineering Three-Dimensional Scaffolds for Cultured Meat Production. Foods, 2023, 12, 2614. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132614

Xiang, N.; Yuen, J.S.K., Jr.; Stout, A.J.; Rubio, N.R.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, D.L. 3D porous scaffolds from wheat glutenin for cultured meat applications. Biomaterials 2022, 285, 121543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121543

Yen, F.-Ch.; Glusac, J.; Levi, S.; Zernov, A.; Baruch, L.; Davidovich-Pinhas, M.; Fishman, A.; Machluf, M. Cultured meat platform developed through the structuring of edible microcarrier-derived microtissues with oleogel-based fat substitute. Nature Communications, 2023, 14, 2942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38593-4